Motte and bailey castles are the stuff of children’s story books: picture a mound surrounded by a ditch and topped with a wooded palisade, inside of which is a wooden or stone fortress. Perhaps knights in armour are seen approaching on horseback, or an elegant lady wearing the inevitable wimple or cone-shaped head dress. Somewhere nearby, colourful flags and banners ripple in the wind.

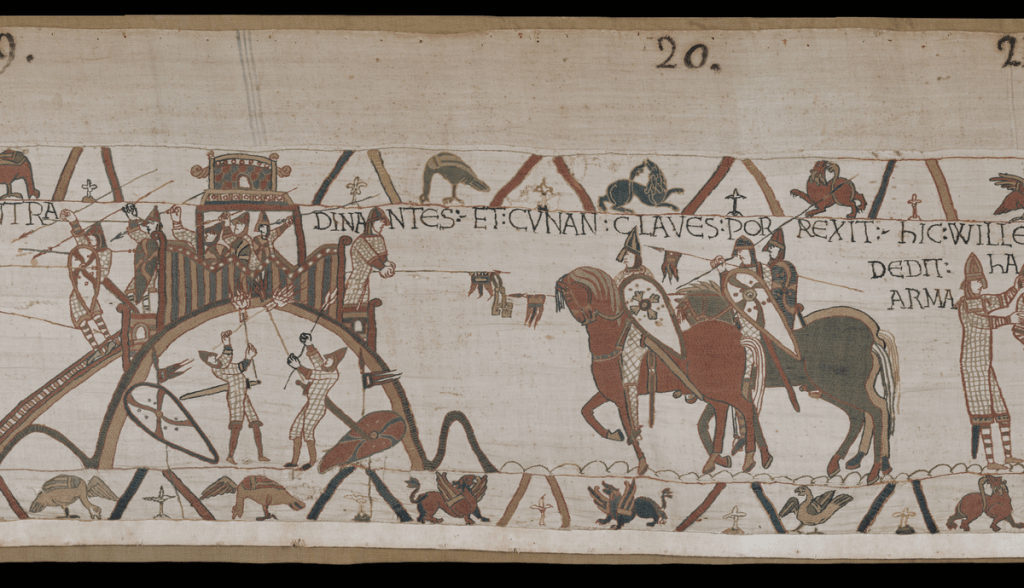

In reality, the motte and bailey castles of history were introduced by the Normans after the invasion of 1066 and an example can be seen on the Bayeaux tapestry:

|

Windsor Castle is an example of a motte and bailey, although over the years of its existence, the building has had much more added to it. By contrast, in Oxford only the motte survives of the original castle construction.

Most interestingly, the OS map of our area records a motte in the village of West Woodhay. A little way from St Laurence’s church, but on the opposite side of the road, and now surrounded by trees, most passers-by will be totally unaware of its existence. However, thanks to the work of O.G.S.Crawford (see a previous post) we can still identify the site of early medieval activity in our area as the word “motte” in a Gothic font is clearly marked on the map. But does the presence of a motte also indicate that there was once a castle, or at least some sort of defensive structure, in the now quiet and peaceful village?

There have never been extensive excavations in the West Woodhay area – perhaps I should add, as of yet. However, in the 1930s enthusiasts of the Newbury Field Club did painstakingly dig the site. Their findings were recorded by one E. Jervoise and you can read what he discovered in volume 7 of the Newbury Field Club Journal in Newbury Library.

The West Woodhay motte is of modest size – the Field Club members recorded its rise to be just 8 feet and the diameter at the top just 30 feet. These dimensions, of course, would have dispelled any expectation of a substantial building so I can forget any fanciful thoughts of a West Woodhay castle. However, red and brown roof tiles and eighty iron nails were found on the crest of the mound, suggesting some sort of construction even if quite small. Broken pottery was found on the top of the mound and in the surrounding ditch, including rims and bases of what was believed to be at least 40 cooking pots or bowls of a type in use in the twelfth century. Some of the sherds found showed traces of glaze. The excavators weighed these finds and found there to be 40lbs of them.

The diggers also recovered soes believed to have belonged to oxen. Also discovered was what Jervoise describes as a “hone” by which he must mean a stone for the sharpening of blades. It had been, “ made of fine grained silicous schist, a rock occurring in Scotland and Normandy.” Most probably a valued or valuable item, then.

Jervoise was particularly pleased by the discovery of a small bronze buckle “of fine workmanship” and having, “an unusually perfect green patina”.

He concluded that it might have been the site of an early medieval hunting lodge and it was certainly somewhere that food was prepared and eaten.

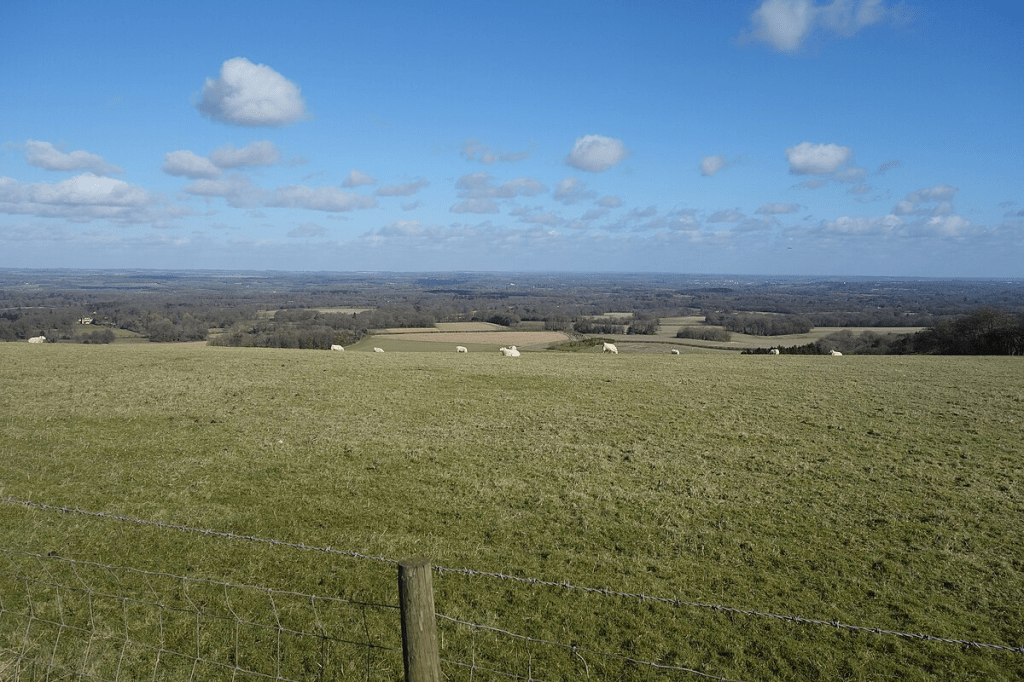

Hunting lodges were not uncommon in the medieval period – a time when a popular sport amongst the nobility was hunting for deer or boar. The lodge would have been the place where visitors, on what in later times might have been referred to as a “straightforward hunting weekend ” would stay or just return after a day’s sport for food and refreshments. With its slightly elevated position on the motte, its view towards Walbury Hill to the south west and the wide open Kennet valley to the south east, the hunting lodge might well have been built to impress.

|

Although the West Woodhay motte was likely never the site of a defensive structure, or indeed anything at all like a castle, I think it is quite safe to assume that the owner of this land in the twelfth century would have been a wealthy man and most likely of Norman descent, speaking Norman French. But while the nobility and upper classes generally would have spoken Norman French, it has to be likely that those preparing the food and washing the cooking pots were of humbler stock. These working people are likely to have spoken the language of the West Saxons or even Middle English – possibly a mixture of both.

Today West Woodhay is in many ways a quintessential English village – typical of many smaller settlements on the southern chalk lands. It is difficult to imagine a time when the English language, as we speak it today, would not have been understood there. Perhaps it is even more mind boggling to imagine a time when the local land owners would have conversed in Norman French!

|

© Theresa Lock January 2025