1830: A time of poverty, resentment and anger

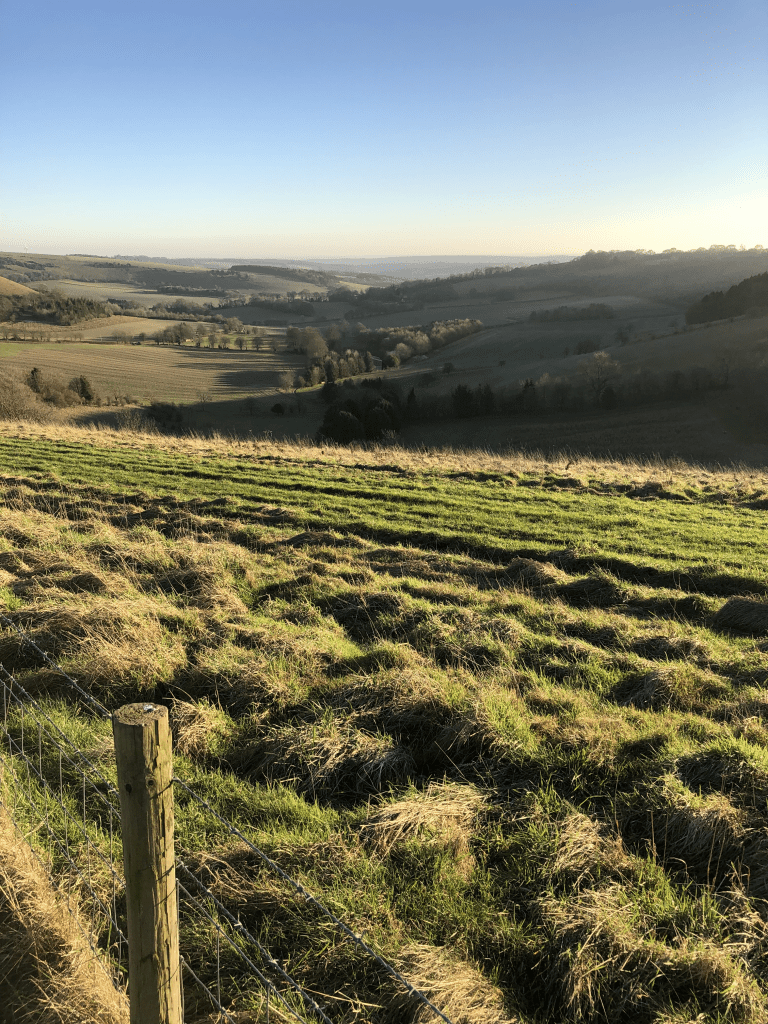

In the early years of the nineteenth century, the industrial revolution was leading to the growth of factories and mills in the rapidly expanding towns of the north and midlands. However, counties in the south of England such as Berkshire remained predominantly agricultural. And it wasn’t just the men who worked the land: many women were employed in agriculture and even children worked on the land rather than receiving an education. As it would be another forty years before the introduction of free education for all, very many poorer people in the earlier years of the nineteenth century had no opportunity to learn to read or write.

A link to the wider world

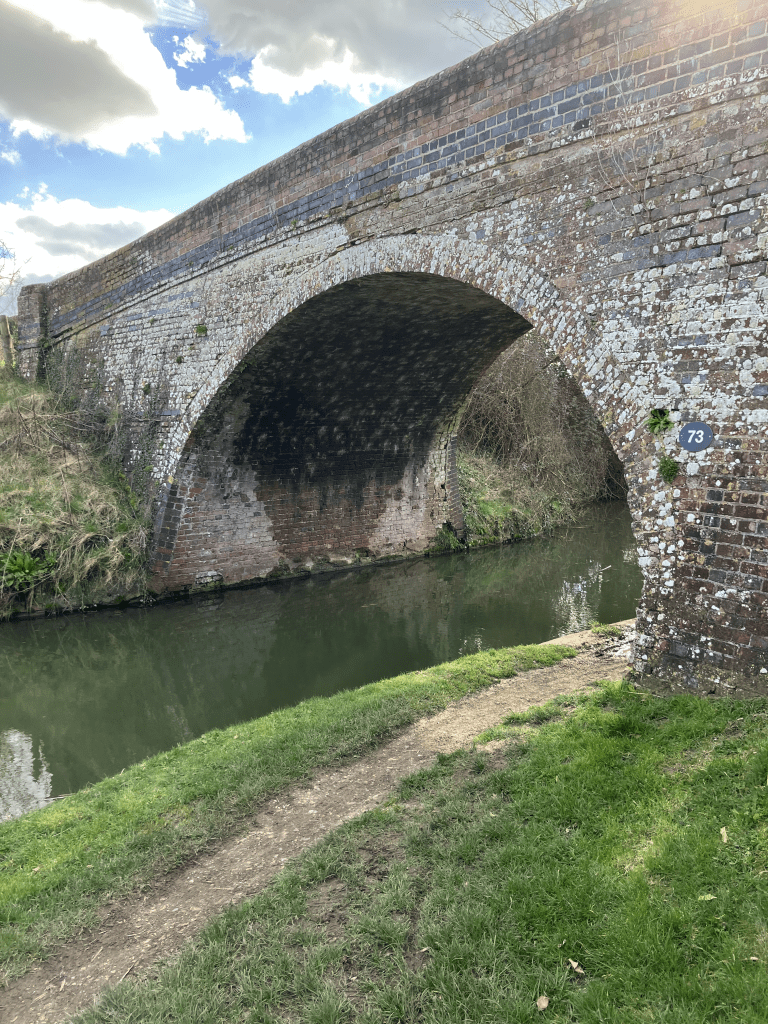

The Kennet & Avon canal had been completed in 1810 so Kintbury people would have become used to seeing colourful barges pass through the village, manned by the itinerate families of bargees; such sights must have seemed strange and exotic to Kintburians who might never have travelled as far as Newbury. Travel for most was by foot or horse drawn vehicle, although occasionally coaches belonging to the better off would have turned off the Bath Road, down what we now know as the avenue, past the church and south through the village.

Whilst families such as those at Barton Court would have lived in comfort and luxury, home for the average agricultural labourer and his family was a very humble cottage, often little more than two or three rooms, sparsely furnished and lit by tallow candles.

Bread on the table

The war with France had ended some fifteen years previously but the peace had also brought with it a recession. Furthermore, 1830 saw the third poor harvest in succession, putting up the price of wheat and subsequently of bread. This was not good news for the agricultural labourer, whose wages for the year had dropped from £40.00 (15 shillings or 76 pence a week) in 1815 to £31 (12 shillings or 59 pence a week) in 1827.

Labourers in other occupations fared a little better with an average pay of £43 a year (16 shillings or 82p a week ). Meanwhile, colliers in the north and midlands averaged £54 a year (slightly over the lofty sum of £1 a week ) and cotton spinners £58.50 a year (£1 / 2 shillings or £1.10p a week ). It was no wonder that many agricultural workers in the north of England were migrating to the urban areas where work in mills and factories promised higher wages. But no such opportunities existed for the agricultural labourers of the south.

These wages were in stark contrast to the annual incomes of those in authority and positions of power. Whilst a clergyman was not considered wealthy within his class, an annual income of £254 or £4/17shillings a week must have seemed a fortune to the labourer. Meanwhile, far removed in their offices in Newbury or Reading, a solicitor could earn up to £522 a year. But this was a world away from the life of the agricultural labourer.

A restricted diet

So how did the agricultural labourer exist on 12 shillings a week? His family’s diet would have been restricted and unvarying, consisting, for example, of bread, bacon, small amounts of cheese, butter, milk, tea, sugar and salt – all carefully rationed. There might have been small amounts of meat other than bacon and some labourers were able to keep a pig. If the cottage garden was large enough and the soil suitable, vegetables could also be grown at home. Research has suggested that 71% of the family’s income would have been spent on bread alone: not surprising as it would have been a staple and eaten at every meal. The Berkshire Chronicle of April 3rd 1829 records the latest price for a gallon loaf in Newbury to be between 1 shilling, 7 pence (1/7d) and 1 shilling, 9 pence (1/9d). Prices, however, varied according to the success or otherwise of the harvest each year.

No more rabbit pie

Whilst previous generations of country dwellers would have been able to augment their diets by catching rabbits and fowl on common land, the Enclosure Acts meant that land owners had been able to fence off vast tracts of land over which the labourers had previously been able to walk freely. It also drastically reduced the areas of land available for the poorer classes to cultivate for themselves. Furthermore, the harsh Game Laws resulted in strict penalties for anyone caught poaching. The law of 1816 imposed the penalty of seven years transportation (ie being sent to a penal colony in Australia) for anyone caught with nets to snare a rabbit, even if no rabbit had been trapped. Until 1827 it was perfectly legal for landowners to set mantraps on their land. These devices could, at best, break a man’s leg and at worst cause him a long and lingering death as a result of his injuries.

Keeping the peace

These are the years before the establishment of police forces across the country: Newbury Borough Police was not established until 1835. Instead, law and order were maintained through a system of harsh penalties designed to deter crime and the only way of dealing with more extreme disorder was to call upon the militia. The death penalty existed for over 200 crimes and for others, those convicted could be transported – a system of dealing with convicts, both men and women, until 1868.

In the towns and villages, watchmen and constables were responsible for keeping the peace and those arrested were taken before the local magistrates. These local magistrates, or Justices of the Peace, represented the face of the establishment for the villagers, and it was their business to uphold the laws enacted by parliament. In 1830, the Houses of Parliament might as well have been on the moon to the working people of England, most of whom were not able to vote until the early years of the twentieth century. One of Berkshire’s two MPs at the time, Charles Dundas, 1st Baron Amesbury, lived at Barton Court, Kintbury. The wealthier villagers, particularly the very few men who were at that time able to vote, might have felt that Dundas represented their interests. This sentiment would not have been shared by the poorer working people.

The Rev Fulwar Craven Fowle

Whilst many villagers might well have been unfamiliar with Charles Dundas other than by name and as the owner of the large and comfortable house along the avenue on the way to the Bath Road, they would have been much more familiar with the local magistrate. The Rev Fulwar Craven Fowle was vicar of Kintbury, the third generation of his family to hold the living. He was also the grandson of Lord “Governor” Craven, sometime governor of South Carolina and previous resident of Hamstead Park. Thus, Rev Fowle was several rungs up the social ladder from the labourers at the very bottom, inhabiting a world far distant from theirs. We know from the letters of Jane Austen – a family friend of the Fowles – that Fulwar Craven Fowle could be bad tempered although there is evidence that he was much loved by his parishioners. Many of the village labourers, however, may very well not have belonged to the Anglican church and are likely to have been members of one of the non-conformist churches (or chapels) and so would not have known Rev Fowle as their priest, but as a magistrate and as a member of one of the better-off village families.

Thus Rev Fowle represented the face of an establishment which had introduced harsh and punitive laws, a system which had reduced the labourer to a life of poverty from which there was no chance of escape.

Representing the people

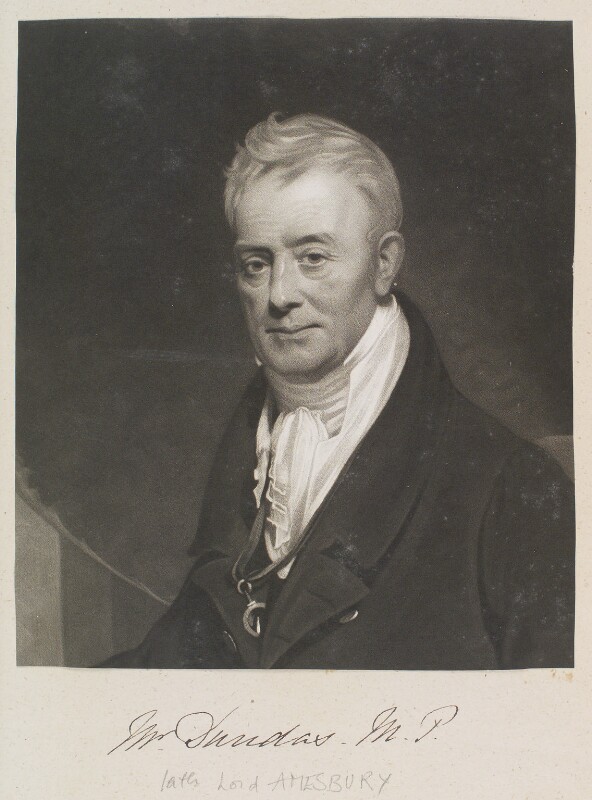

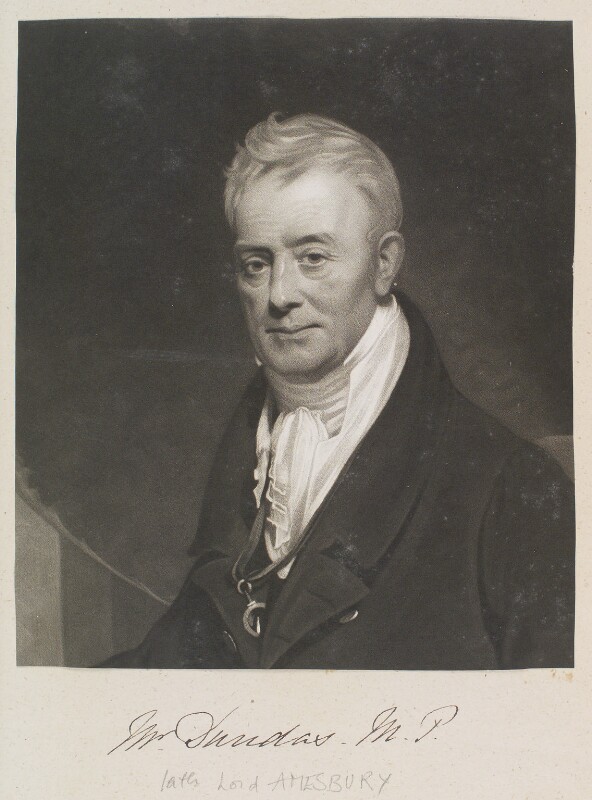

Charles Dundas, Baron Amesbury

by William Say, after Sir William Beechey

mezzotint, (1823)

NPG D11326

In 1830, only around 5% of the people were eligible to vote and, with the exception of a few women living in some towns, those who could vote were all men. There was much political corruption and some constituencies were always represented by certain, influential families. In Berkshire, Abingdon (then in Berkshire) returned one member of parliament, Reading two and Wallingford (also in Berkshire at that time), also returned two MPs. The rest of Berkshire – which then stretched as far north as the Thames –was represented in total by just two MPs. In 1830, these were Robert Palmer and the resident of Barton Court, Kintbury, Charles Dundas. Over the border to the west, Great Bedwyn, smaller than Hungerford, returned two MPs, and further south in Wiltshire, Old Sarum – a place with no inhabitants at all, continued to send two MPs to Westminster.

So whilst Members of Parliament were responsible for passing the laws which severely restricted the lives of the working people, causing much hardship, those MPs were answerable to very few. And those who could vote lived their lives pretty much untouched by the kind of challenges afflicting the poor.

Know your place

There existed a very clearly defined class system in England at this time. At the top of the social ladder were the nobility such as William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne, the Home Secretary in 1830. Letters addressed to him begin, “My Lord…”.

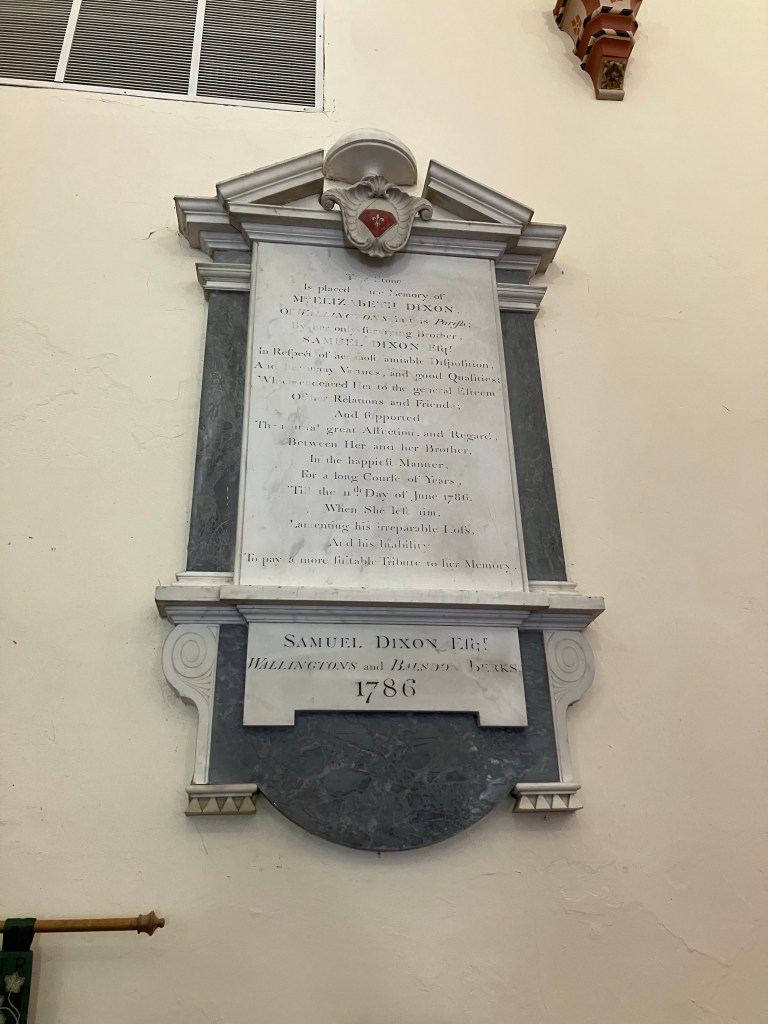

Further down the social ladder, but still a long way from the bottom, those of the landowning classes who did not have titles have “Esq” – short for “esquire”- after their names whilst those on the next rung down are referred to as “Gentlemen”.

Newspaper reports of this time often refer to “gentlemen and farmers”, because a farmer was not necessarily also a “gentleman”. However, the farmer was several rungs above the labourers who worked for him. These labourers are not even afforded the title, “Mr” and in some reports are referred to as “the peasantry”.

The popular hymn, “All things bright and beautiful”, published in 1848, originally included the verse which read:

The rich man in his castle,

The poor man at his gate,

God made them high and lowly,

And ordered their estate.

Campaigning for change.

It is not surprising that there was, throughout England, a growing movement advocating reform. However, many who could remember the events of the French Revolution of the 1790s, which had seen the overthrow of the monarchy and the execution of many members of the upper classes, continued to fear that something similar would happen in England. Demands such as the right for everyone to vote, equal rights before the law or the abolition of child labour – all of which seemed perfectly reasonable to many – were regarded by some members of the establishment as a threat to their way of life and a slippery slope towards a repeat in England of what had happened in France.

By contrast, the events in France had inspired others to advocate reform of parliament and the law. One such was the wealthy farmer from Wiltshire, Henry Hunt, an inspirational speaker who had been given the nick-name “Orator” Hunt. In 1819, he had been invited to speak at a rally in Manchester which was attended by a crowd of around 60,000 people. Fearful of the effect one of Hunt’s rousing speeches would have upon the crowd, the local magistrates panicked and sent in the militia, who were armed with sabres. In the resulting massacre, up to fifteen people are believed to have been killed and hundreds injured.

Another radical thinker of the period was William Cobbett, the son of a farmer from Surrey who had become involved in political debate and the need for parliamentary reform. Cobbett was also a journalist and as well as essays and letters he published a weekly newspaper called The Political Register which soon became popular amongst the poorer classes. Not everyone was able to read Cobbett’s newspaper for themselves but it is likely that those lucky enough to be literate would have read aloud to others and so the views expressed were shared more widely than the circulation of the paper copies.

William Cobbett

possibly by George Cooke

oil on canvas, circa 1831

NPG 1549

It is very likely that that copies of The Political Register would have been shared or read aloud, perhaps in the public houses or other meeting places, around Hungerford or Kintbury such that the poor and oppressed rural labourers became aware of those who had already set out to challenge the status quo.

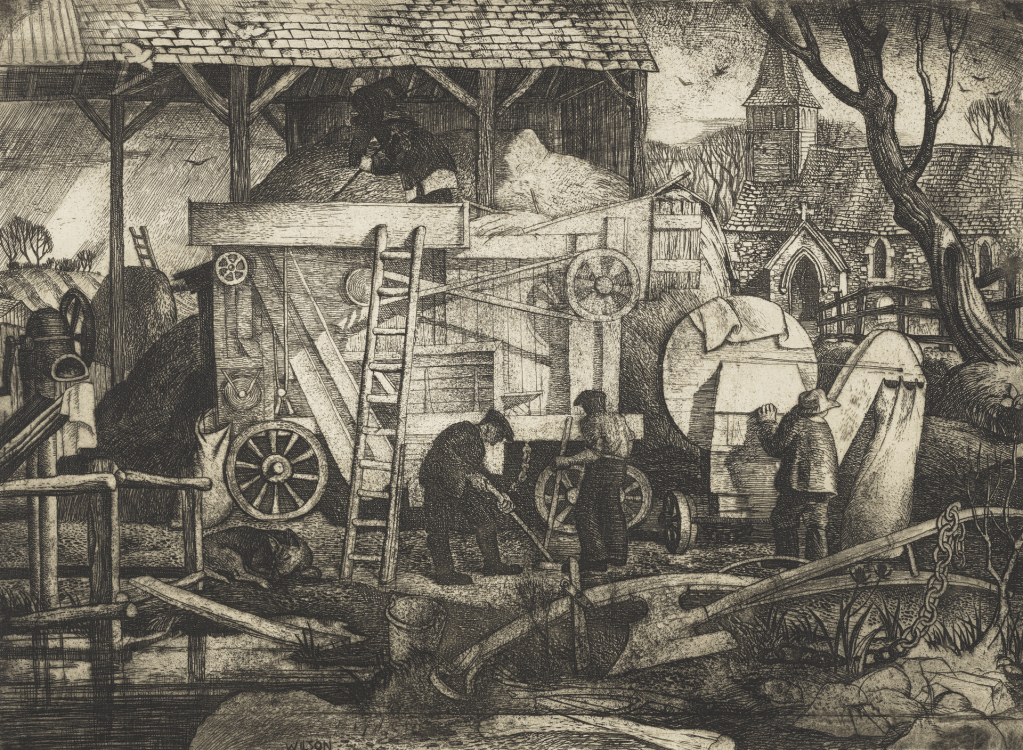

The Threshing Machine

The Threshing Machine , William Wilson © Estate of William Wilson OBE RSA

National Gallery of Scotland

Threshing is the process of separating the grains of wheat from the chaff. Before the introduction of threshing machines, this was a very labour intensive process done by hand using a flail. Threshing took place in the autumn after the harvest had been brought in and provided employment for hard-pressed agricultural labourers at a time in the year when there was very little other farm work available. At a time when wages were lower than ever and the price of bread increasing, what the farm labourer could earn by threshing helped to keep him and his family throughout the bleakest part of the winter.

Threshing machines required very few labourers to operate them so their introduction meant the loss of work for many men. And loss of work at such a crucial time meant, for many, the fear of starvation throughout the winter months.

Many agricultural workers literally feared for their lives.

Bibliography

Griffin, Emma, (2018), Diets, hunger & living standards during the British industrial revolution, Past & Present.

Lindert & Williamson, (1983), English workers living standards in the industrial revolution, The Economic History Review

Phillips, Daphne (1993), Berkshire: A County history, Newbury: Countryside Books

Thompson, David (1969), England in the nineteenth century, Pelican

Trevelyan, G.M.(1960) Illustrated English Social History:4, Pelican

Woodward, Sir Llewellyn (1962), The Age of Reform, Oxford: OUP

Theresa A. Lock, Kintbury, October 17th, 2020.