In January 1801, Jane Austen wrote to her sister Cassandra,

Eliza has seen Lord Craven at Barton, & probably by this time at Kintbury…

The Eliza she mentions here was the wife of the Rev Fulwar Craven Fowle, vicar of Kintbury, and Lord Craven the influential land owner and member of the aristocracy then living with his mistress at Ashdown Park. But where was Barton and why was whoever lived there playing host to a local “bigwig”?

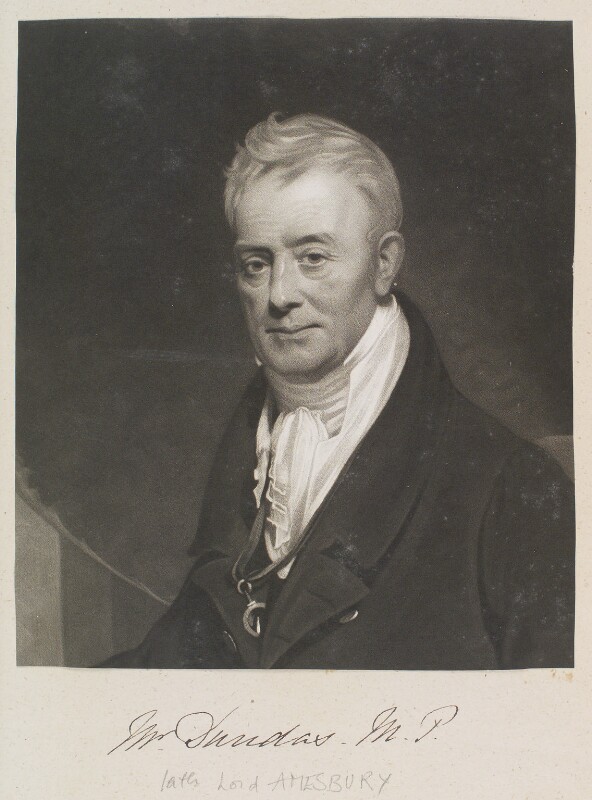

Barton – or Barton Court – still an imposing residence which can be reached along the Avenue, at that time the main route into Kintbury for traffic from the Bath Road, was the home of Charles Dundas. Since 1794 he had been Member of Parliament for the constituency of Berkshire, at that time stretching as far north as the Thames and including Wantage and Abingdon. As a member of a titled Scottish family, Dundas moved in some of the best circles of the time.

In keeping with their station in life and the fashions of the time, the Dundas family are well represented on the walls of Kintbury church where we can read that Charles and his wife, Anne Whitley, whom he had married in 1782, “had issue one daughter, Janet”. Anne died in 1812 and in 1822 Charles married Margaret Erskine, formerly Ogilvy, née Barclay.

Reading the Dundas memorials on the church walls, anyone would conclude that Charles Dundas had just one daughter. However, research into historical records reveals that this was not the case. Charles’ daughter Marrianne was most likely born in 1793. Her mother was not Anne Whitley. At the time, a child born to a mother not married to its father was often referred to as the “natural” child of whoever; Jane Austen gives an example of this in her novel, Emma, where Harriet Smith is referred to as the “natural” daughter of an unknown person Emma choses to imagine as someone well-to-do. Harriet Smith has been sent to live at a boarding school for girls and, it seems, no one acknowledges her as their daughter and her family remain a mystery.

We know from looking at the 1851 census that Marrianne had been born in Kintbury but I can find no record of her baptism or indeed who her mother might have been. It is impossible to find out anything of her early life – perhaps, like Harriet Smith, she was sent away to a girls’ boarding school. However, thanks to online marriage records, we know that in 1815 Marrianne Dundas married the Rev William Everett of Romford, Essex at the then very fashionable St George’s, Hanover Square, Westminster. We know Charles Dundas was present at the ceremony as he has signed the register.

It is particularly interesting that Marrianne is known by her father’s surname although all the available evidence suggests that Charles Dundas was never married to her mother. This was a time when a “natural” son or daughter was usually known by their mother’s surname, an example from Kintbury being William Winterbourn who, during his lifetime, was known by his mother’s name of Smith as his parents weren’t married. It would seem to me that, by the time of her marriage at least, Charles Dundas acknowledged Marrianne as his daughter.

Marrianne and William Everett had three children: William, born and baptised in Kintbury in 1821 became a fellow of New College, Oxford and also a barrister; Charles Dundas Everett, born in Kintbury in 1825 entered the church; finally Alicia was born in Kintbury 1827. Interestingly, the 1861 census actually shows Alicia having been born at Barton Court so it has to be likely that her brothers were born there, too. There is no evidence that the Everett’s family home was ever in Kintbury; perhaps it had been decided that Barton Court was a preferable place for a confinement that the Rev Everett’s draughty vicarage!

We can only assume that Charles Dundas’ second wife was welcoming to Marrianne and her children.

On November 27th 1851, the youngest child, Alicia, married the Oxford master brewer, James Morrell of Headington, at St George’s, Hanover Square – the same fashionable church at which her parents had married. The service was taken by her brother, Charles.

James had inherited Headington Hill Hall which he had extended in the Italianate fashion and this large, imposing residence became the family home for him and Alicia. Marrianne was living there herself when she died on 4th December 1861.

James and Alicia’s only child, Emily, was born in 1854. In 1874 Emily married her cousin, George Herbert Morrell and so the Oxford brewing business continued to be run by the Morrell family for the next three generations. By the 1960s the company was run by one Colonel Morrell, a well known name in the Oxford area, not least in the Lock household as my father’s firm did a lot of work for the brewers. I believe Colonel Morrell would have been Marrianne’s great, great grandson. The natural daughter of Charles Dundas, therefore, can be regarded as the dowager matriarch of Oxford’s celebrated brewing family.

In 1953 the Morrell family sold Headington Hill Hall to Oxford City Council from whom it was later leased by one Robert Maxwell, infamous for having defrauded his employees’ pension fund and having disappeared from his yacht named the Lady Ghislaine, after his daughter.

Today, Headington Hill Hall is leased by Oxford Brookes University.

So, whilst there are many Dundas names on the walls of Kintbury church, Marrianne’s – due, I suppose, to the circumstances of her birth – is not one of them. But despite being Charles Dundas’s “natural” daughter, her fate was not that of a Harriet Smith. Her life might not be recorded on the walls of our church but through the generations her family certainly made their mark in Oxford.

One mystery, however, remains: there seems to be no way of knowing the name of Marrianne’s mother. That chapter of her story is no different from that of Harriet Smith.

Theresa Lock, July 2023

Photograph of Charles Dundas reproduced under creative commons licence: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/