We know the names of the village men who died in the First World War as they are recorded, quite rightly, on the war memorial and in the church. However, it is much more difficult, at over a hundred years’ distance, to find the names of those who returned to the village in the months after the armistice. But, with a bit of help from the archive of the Newbury Weekly News, the library at the Museum of English Rural Life and other sources, we can find something of the world to which they returned.

We know that many of the men who returned to Kintbury would have been agricultural workers so for the purpose of this article, I have invented a fictitious agricultural worker, Fred, his wife, Mary and their friend, George.

However, the historic details relating to the Kintbury of 1919 are all factually correct.

************************************************************

Fred had signed up in 1915 and spent the last months of war on the western front. In the summer of 1918 he had been able to return to Berkshire to marry his childhood sweetheart, Mary.

Men who had jobs to return to were able to be demobbed sooner than those who had no work waiting for them. Fred’s employer was keen to have him back on the farm so by early 1919 Fred was able to rejoin Mary at home.

Fred would never speak of the horrors he had witnessed in France and Belgium and only Mary would know that his sleep was frequently interrupted by nightmares. Fred hid all that from his family as he and Mary tried to build their new life together.

Homes for Heroes?

Before the general election in 1918 there had been much talk of the proposed, “Homes for Heroes” to be built by local authorities for a controlled rent. Mary had allowed herself to dream that perhaps, one day, she and Fred would have such a house in Kintbury – her Fred, after all, was a war hero. But Mary was to be disappointed – although the Rural District Council had selected sites in Kintbury by May of 1919, it was the 1920s before the council houses were built in Burton’s Hill. So their first home together was a tied cottage on the farm for which the farmer was legally entitled to deduct up to 3 shillings (15p) a week from Fred’s wages.

But Fred and Mary tried to be optimistic: working conditions for farm workers were improving. By 1919 working hours were set at 50 hours a week in the summer and 48 in the winter and by October the minimum weekly wage in Berkshire was 36 shillings and 6 pence (36/6d or £1.82). It was certainly an improvement, but Mary was very well aware that a new pair of boots for Fred would cost nearly a whole week’s wages – and probably need replacing in six months. And while she looked longingly at the new ladies’ shoes advertised in the Newbury Weekly News for sale in one of the town shops, she knew that at 35 shillings and 9 pence (35/9 or £1.80 ) a pair, they were way beyond her household budget.

Changing times?

Some of Fred’s workmates joined the National Union of Agricultural Workers – they said that it was down to the unions that working conditions improved. Fred thought that might be true, but prices were still going up so life was not easy. George, one of Fred’s mates, was a new and very enthusiastic member of the Labour Party and in March he walked along the tow path to Newbury to attend a meeting of the local branch in the Temperance Hall in Northcroft Lane. Fred was not sure about this; in the recent election, Conservative & Unionist candidate William Mount was returned for the Newbury Constituency unopposed and to Fred this seemed to represent security.

On your bike?

Fred did not have a bicycle so he would have had to walk into Newbury or pay to catch the train. A.C. Bishop of Bartholomew Street advertised their latest shiny models, but at £12/10s (£12.50) for the cheapest model, Fred could see that he would be relying on Shank’s Pony for a long time yet.

Horse Power.

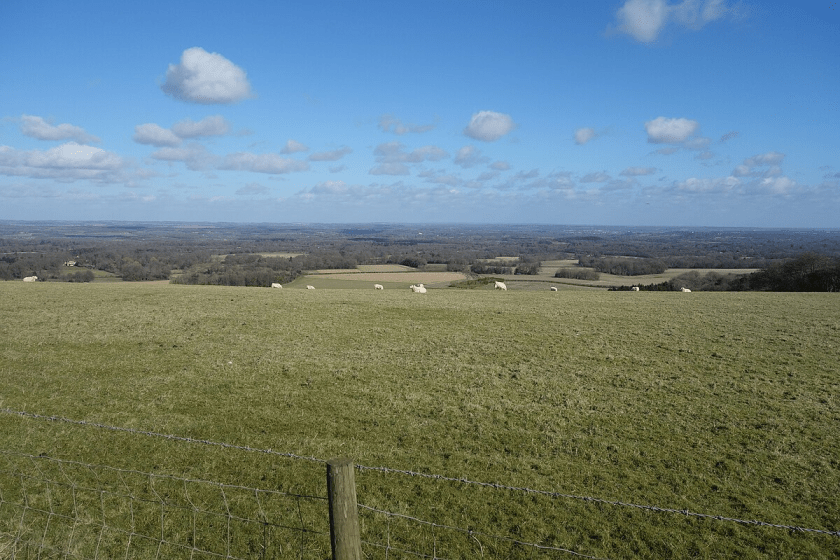

At the farm on which Fred worked, heavy horses were still used to pull the plough and the carts. It is a sad fact that many horses had been requisitioned for the war effort and, like the carters who had worked the land with them, they never returned but had died on the battlefields. The shortage was so bad that there was a government initiated scheme to replace the horses with tractors. In Newbury, Toomers were advertising a Fordson tractor for £280.00 or a Titan for £385.

“God speed the plough and the woman who drives it”

Throughout the war women had been recruited to join the Women’s Land Army, then sent to farms to replace the men who had enlisted. Mary had heard that it was not easy to get accepted: a majority of the young women who applied were rejected for one reason or another. Despite this, by 1918 there were over 223,000 women working in agriculture. Mary did not join up herself, but she did work at the farm on which Fred had been employed, doing the milking and other dairy work. When the time came to give up this work and return to being a full-time housewife, Mary felt quite sad if truth be told. But times were slowly changing for women, Mary believed, and soon she would be able to vote in elections, just as many men had done for years. One day, Mary knew, there would be a woman in parliament. Perhaps even as Prime Minister.

A motor car? Are you having a laugh?

Throughout 1919 Pass & Company of Newbury ran advertisements in the Newbury Weekly News for the Ford “After War Touring Car” which would set you back a mere £250 should you be tempted to buy one. Fred could never imagine that he or any of his family would ever own one – the cost represented two and a half times his yearly wage and seemed to emphasise the gulf between the wealthy and the working man.

“Full equality is impossible”

In May, political discussion came to Kintbury when a meeting of the Kintbury Branch of the South Berks Women’s Unionist Association, an organisation of the Conservative party, was held in the Coronation Hall. In attendance were many well known ladies of the village including Mrs Dunn and Mrs A.E. Gladstone. One speaker, the Hon Ethel Akers-Douglas spoke of the urgent need for self education with regards to politics. Another, Mrs W.A. Mount, wife of the local Member of Parliament, spoke of the “threat” of a Labour candidate in the constituency at the next general election. She explained the party’s intentions to see the conditions of the working men improved, however, “when people said there could be full equality, it was their duty to point out that such a state of things was absolutely impossible.”

When the Newbury Weekly News ran a report of the meeting in its next edition, there were mixed reactions amongst those who read it. Some people wanted to tell Mrs Mount what they thought, and it wasn’t polite. Others felt it was only right and proper that there should never be full equality. They recalled the words of the hymn:

The rich man in his castle,

The poor man at his gate,

God made them high or lowly,

And ordered their estate.

No one wanted the terrible things that had happened in Russia to happen here. To many, the status quo represented security. Mary was not so sure.

I’m part of the union

Meanwhile, in Hungerford members of the National Union of Railwaymen organised a meeting at the Corn Exchange. It was attended mainly by agricultural workers including George, who listened to speeches calling for better conditions as to wages & housing and improved parliamentary representation. The enfranchisement of women should now be seen as a boon to be appreciated, the assembled workers were told.

The next train arriving…

Throughout the year, more soldiers returned to their homes although the lads who had left the village months or years before, had, as a result of all they had experienced, been changed forever by it. Many, of course, were never to return home.

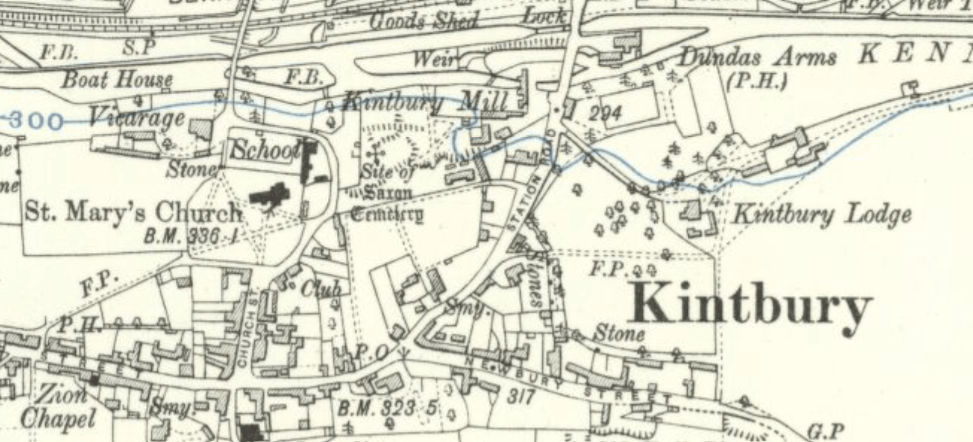

For Fred, it was good to see friends arriving back at Kintbury Station with its familiar and homely Great Western waiting rooms and ticket office. Throughout the war, the railway had witnessed increased traffic through Kintbury with troop transport, munitions and ambulance trains. Soon, however, the only trains to pass through would be carrying freight or passengers about their peace time business.

Celebrating Peace

By the summer of 1919 many towns and villages were preparing to celebrate the end of hostilities. Saturday, July 19th was declared both a public holiday and a Bank holiday for “National Peace Rejoicings”. In Newbury, there was a procession including discharged soldiers, men in uniform (sic ), wounded soldiers, war workers, Boy Scouts and Girl Guides.

In Hungerford, there was a Peace Thanksgiving Service at St Lawrence’s church. The children of Lower Green, Inkpen enjoyed a “splendid fete” while those of Inkpen Common were, “entertained to tea in Mr Ward’s warehouse and one hundred and eleven sat down to a capital spread.”

Unfortunately, and to the disappointment of the children of Kintbury, plans for a celebration in the village fell through.

Plans for a recreation ground

In Kintbury a public meeting was held at the Coronation Hall at which it was decided that, to perpetuate the acknowledgement of those who had been engaged in the war, a plot of ground suitable to form a recreation place for the parish and especially for children, should be purchased, leased or acquired. Subscriptions were invited.

Fred considered this to be a very good plan. Recent changes in the working conditions of agricultural workers like him meant that they were able to take Saturday afternoons as a half day holiday most weeks. This resulted in the return of village sports such as football and so a proper, dedicated football field would be welcomed.

Keep the red flag flying….

The Conservative & Unionist candidate, William Mount, had contested the Newbury constituency unopposed in the election of 1918. However, it seems the Newbury branch of the Labour Party remained optimistic. In August they organised a procession with banners leading to a mass meeting in Victoria Park. A resolution was carried saying that the time had come for greater parliamentary representation.

George had joined the Labour Party; he told Fred that, since his return home from France he had begun to see things differently and now he wasn’t going to doff his cap to anyone. God had created all men equal, hadn’t He? That William Mount had better look out because come the next election, Newbury would have a Labour candidate just like they’d done last time in Reading.

The Railway men strike

Several men from the Kintbury area worked for the Great Western Railway. In September their union, the National Union of Railwaymen, called them out on strike. This seemed wrong to Fred who disliked any form of conflict, though his mate George said it was because there was a threat to reduce their wages, and that wasn’t right. To Fred’s relief, the strike was soon called off and it seemed as if the railway workers had achieved what they wanted. But the fact that the men had gone on strike at all still seemed to worry some people.

Newbury MP addresses meeting in Coronation Hall

No less a person than the MP for Newbury, William Mount, addressed a meeting at the Coronation Hall. Mary was insistent than she and Fred should attend saying that Mrs Akers-Douglas herself had said that women should now learn more about politics. She’d read it in the Newbury Weekly News so it must be so. Fred was reluctant but on Mary’s insistence they both donned their Sunday best and took up their seats at the very back of the hall which was filling up, Fred noticed uneasily, with Kintbury’s wealthier inhabitants.

Mr Mount was very careful not to criticise the railway workers themselves: he described them as “pleasant and agreeable”, “loyal and patriotic.” But he was very critical of their union, which had, apparently, declared a strike without a ballot, which was very, very wrong. Furthermore, he insisted that the railwaymen were paid a good wage. Fred noticed that Mr Mount said nothing about the proposal to cut their wages, so perhaps George had got that wrong.

Those listening in the Coronation Hall clapped appreciatively and there were calls of “Hear, hear” when the MP spoke of the dangers of electing a Labour government.

As they filed out of the hall onto the Inkpen Road, Fred could hear the comments of others. Mr Mount was being described as a “thoroughly good fellow”, “exactly the kind of person we need” by people he knew and respected around the village. Perhaps they were right.

Mary saw things differently. She said that it was all well and good for Mr Mount because he never had to worry about where the next meal was coming from. Those shoes he was wearing, they didn’t cost him a whole week of his pay, did they? He didn’t have to count up the pennies in his purse before he went to the local shops, did he? Just wait until we have some women in parliament, Mary said, women who really know what the housekeeping costs.

(Regarding Mr & Mrs Mount, in 1919 they would have no way of knowing that in 2005 their great, great grandson, one David Cameron, would become leader of the Conservative party, and in 2010, Prime Minister.)

Moving slowly forward.

By late summer, Giles’ Motor Bus resumed its service between Hungerford, Kintbury and Newbury. However, the service ran on three days each week only – Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays, departing Kintbury at 10.35.

In September the Kintbury Choir Boys’ Outing was to Southsea in a charabanc – a kind of open-topped bus popular at the time for day trips.

Party time at last!

Although several local villages had held peace celebrations on the designated Peace Day, July 19th, Kintbury children had to wait until September 24th for their party, when, according to the Newbury Weekly News, “Kintbury threw aside its mantle of tranquility…the young folk giving themselves up to mirth and merrymaking.”

The party had been organised by Miss Agnes Langford and money had been raised in various ways: “A jazz band was formed and they paraded the village, stirring up the inhabitants and disturbing the peace and quietude with their trombones, concertina, triangle, cornet, euphonium, kazoos and big drum.”

£2.19s 11d ( £3 all but an old penny ) was raised by the efforts of the band and the final sum amounted to £24 3s 6d – a sum equivalent to thirteen weeks’ of an agricultural worker’s pay.

On the day of the party, the children assembled in the Market Square and marched to Wallington’s Park at the invitation of Mr & Mrs A.S. Gladstone. Seated at long rows of tables, the children enjoyed tea, bread and butter and fancy cakes. Afterwards, apples were distributed and the children adjourned to the park meadows for games and races, for which there were money prizes.

The day ended with a procession of children marching around the terrace in front of the house where they were each presented with a mug decorated with “Britannia and Allied Flags” as well as the Kintbury crest. A total of 350 mugs were presented and the children were also given buns, cakes and apples to take home.

Still undecided…..

On October 16th there was a public meeting in the Coronation Hall to further consider the question of a war memorial. At Christchurch a memorial cross – 9 feet high and made of oak with a bronze figure of Christ –had been dedicated four months previously.

Plans agreed earlier in the year to dedicate a recreation ground to the memory of the fallen seem to have fallen through. At another meeting in the Coronation Hall, this time on October 30th, someone suggested building a swimming pool for the village. However, the plan finally decided upon at this meeting was for the establishment of a Men’s Club.

To celebrate the first anniversary of the signing of the armistice, a Whist Drive and Dance was held in the Coronation Hall, finishing at 1.30 am.

Mind your own business

In November, Kintbury readers of the Newbury Weekly News must have been surprised to read the following in their weekly paper:

“A young man of the village would be much obliged if certain Kintbury people would mind their own business. If they do not, steps will be taken.

If some of the kind people of Kintbury would mind their own business rather than look after other people’s it would be more to their own credit and to prove what they say is the truth. E.E.P.”

Neither Fred nor George knew who E.E.P. was. It seemed a strange way to express your annoyance or anger: in the small ads column of the Newbury Weekly News.

A year’s end

As the first year of peace drew to a close, it would seem that Kintbury had finally made a decision about something: at a meeting in the Coronation Hall – where else?-on November 10th it was decided that football should be revived in the village and that the colours of the team should be the old ones of amber and black. The trustees of the Benham Estate had offered the use of a ground at Barton Court, to be accessed along the Avenue, and this was accepted.

Men such as Fred and George welcomed the return of their favourite sport, particularly as the agricultural workers were now able to take a half day holiday on most Saturdays. For Fred, however, his feelings were mixed; it might seem illogical but to him it felt wrong somehow that he was able to enjoy a game on an autumn Saturday when so many of the lads he had played with before the war were no longer there. Fred felt he had no right to be back home, back on the football pitch, back enjoying himself. But like so many of his feelings, his emotions, he hid them and told no one.

Mary tried to lighten his mood with a joke. If she was to stand on the cold and windy sidelines cheering Kintbury on, well, she’d want a new coat, wouldn’t she? How about Fred buy her one of those advertised in the paper? McIlroy & Rankin in Newbury had Ladies’ Heavy Winter Coats for only 55/- (£2.75p).

When the cows come home by themselves, Fred told her. When the cows come home…..

The revived Kintbury team played their first match on a snow-covered pitch. The result:

Kinbury: 4 Newbury Guildhall: 0

Something to celebrate!

(C) Theresa Lock 2025