The church’s restoration,

In eighteen eighty-three,

Has left for contemplation,

Not what there used to be.

John Betjeman

Many church guide books will proudly tell you that St Whoever’s is a fine example of, say, Norman architecture. It is easy to imagine, as you sit in your pew, listening to this week’s sermon, that the church you see around you is more or less the same building that, for example, knights would have known as they stopped off on their way to the crusades, carving on the Norman pillars the familiar crosses while their horses chewed on the church yard grass outside.

Although there are very few churches which exist today just as they were when the last mason knocked off work for the last time and the building was consecrated, it was the Victorians who were responsible for the greatest changes to our much-loved buildings. By the nineteenth century, many ancient buildings might well have required building work but in their enthusiasm for what they chose to call restoration, the Victorians swept away many significant features, and at times, entire buildings.

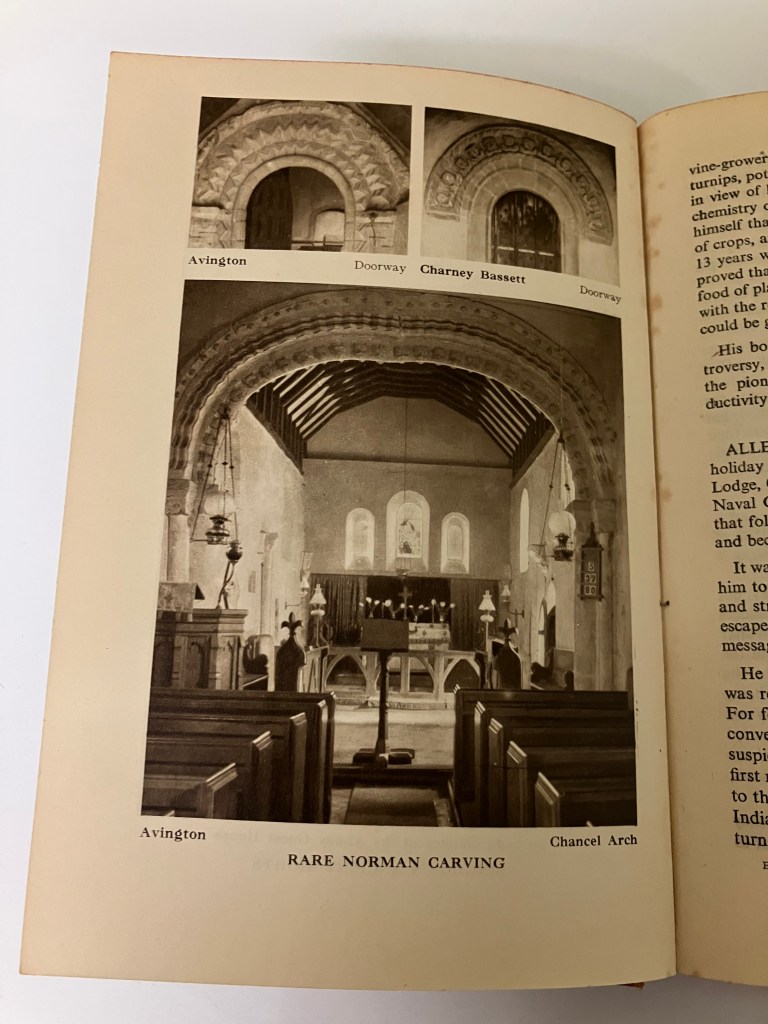

In the Berkshire volume of his series, The Buildings of England, the architecture historian Nikolaus Pevsner, describes St Mark & St Luke’s church at Avington as being, “A memorable little church … Entirely Norman …” so perhaps the crusade-bound knights of my imagination would have seen the very-same church that we see today. Except, that is, for the pulpit and pews, which are Victorian. Also the vestry. And the stained glass, of course.

So how did the other churches in our benefice fare during the nineteenth century?

St Mary’s, Hamstead Marshall seems to have survived the Victorian enthusiasm for restoration relatively unscathed, leaving earlier architectural features as they were. Pevsner says the building underwent a restoration in 1893 and another in 1929 – 30, “preserving and enhancing the C17th & C18th character of the interior.” Perhaps, therefore, the interior of this beautiful church does not look so very different as it did when the first battle of Newbury was being fought in 1643, just a few miles up the road. Perhaps a battle-weary soldier, either cavalier or roundhead, might have staggered into this church and seen before him an interior almost identical to that which we see today.

But what about the other churches?

I used to imagine Jane & Cassandra Austen would have known St Mary’s, Kintbury, just as I know it today, but this is far from the case. In 1859, the architect responsible for the now long-gone Christchurch and also the former vicarage, Thomas Talbot Bury worked on St Mary’s in what Pevsner refers to as a heavy-handed restoration. More restoration work followed 1882 – 84 by George Frederick Bodley & Thomas Garner. All three architects worked in the popular Gothic Revival style which took its inspiration from the medieval buildings much admired by the late Victorians.

In St Mary’s, many changes and remodelling included moving the Scheemakers monuments from their original position by the altar to their present one in the north transept. The gallery was repositioned to its present position under the tower and plans were proposed to enlarge the building, although this never happened. The eye-catching, brightly painted reredos is a Bodley & Garner addition, so one way and another Jane Austen’s view of the altar – in fact the church as a whole – would have been very different to ours.

Pevsner describes St Michael’s at Enborne as “an aisled Norman church” so could this delightful building really be almost exactly the same today as it was when my (imagined) knights passed through on their way to Jerusalem? Unfortunately, although Enborne church retains many Norman features, it did not escape the enthusiastic hand of the Victorians. However, it seems that there might have been a good reason for the work. The Newbury Weekly News of 12th January 1893 included an article in which the Rector of St Michael’s is quoted as saying, “The church at present is in such a dilapidated state that the less said about it the better unless it is of a view of increasing the Restoration Fund at the Newbury Bank. The plans are the result of much care and thought.”

The Reading Mercury of August 12th 1893 reported:

“The restoration of St Michael’s, Enborne is being satisfactorily carried out by Mr G. Elms of Marsh Benham under the direction of the architect Mr James H. Money.”

Apparently, the diocesan architect had recently visited the church along with James Money:

“… and has testified to the great pains being taken to render the restoration a favourable one in all aspects.”

Clearly, not everyone approved of what was being done, although there is little evidence of dissenting voices in the local papers.

On March 6th 1897, the Reading Mercury reported on the rededication of St Michael & All Angels’ church, Inkpen, it having been “in restorer’s hands” for more than a year. The rector, the Rev Henry Dobtree Butler believed it had “long fallen into a lamentable state of decay” and so the grandly named Oxford architect, Mr Clapton Crabbe Rolfe, had been engaged to carry out a restoration. And a very thorough job he did of it, too. The Reading Mercury went on to report:

“The greater part of the church has been rebuilt and a new north aisle added …

The only ancient portions of the actual fabric are the exterior walls and one west window.”

Whilst the tone of the Reading Mercury’s report suggests that the destruction of much of the original building was a positive thing, not everyone agreed. According to Pevsner, the recently formed Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings had opposed the drastic restoration. Founded in 1877 by William Morris and Philip Webb, SPAB was concerned that the fashionable enthusiasm for restoration was destroying the historic fabric of many venerable buildings.

Despite his opposition to the fashion for extreme restoration, William Morris contributed work to many churches, including St Laurence’s, West Woodhay. Here, the red brick church which had stood next to West Woodhay House since 1716 was demolished and a church designed by Sir Arthur Blomfield built on a new site in 1882. The distinctive east window was designed by Burne Jones for Morris & Co as were the side windows of the sanctuary. On 15th April, 1882, the Hampshire Chronicle waxed lyrical in their appreciation of this new amenity:

“The inhabitants of West Woodhay … have reason to congratulate themselves upon having in their midst a resident lord of the manor whose liberality bids fair to effect a great improvement in the social position of all in the village.”

Quite how the new church would effect a great improvement in the social position of the cottagers of West Woodhay, the Hampshire Chronicle does not explain!

So, there is nothing ancient about St Laurence’s, West Woodhay and it remains the only church in our benefice to represent just one period of church building. But this beautiful little church demonstrates, I think, some of the very best of Victorian architecture and design. No crusade bound knight in shining armour may ever have passed through passed through its door. No weary parliamentarian would have sought sanctuary from the battle field to the north. But it is beautiful, all the same.

And I would very much like to know if William Morris or Edward Burne Jones ever visited in person!

© Theresa A. Lock 2024