Filmed entirely on location around Inkpen and Combe with many scenes shot on Walbury Hill, the plot of the film is based on true events. These were the murders in 1676, of Combe ’s Martha Broomham and her son Robert, by Martha’s husband George and his lover, Dorothy Newman of Inkpen. The murderers were executed at Winchester and their bodies subsequently displayed on Combe gibbet.

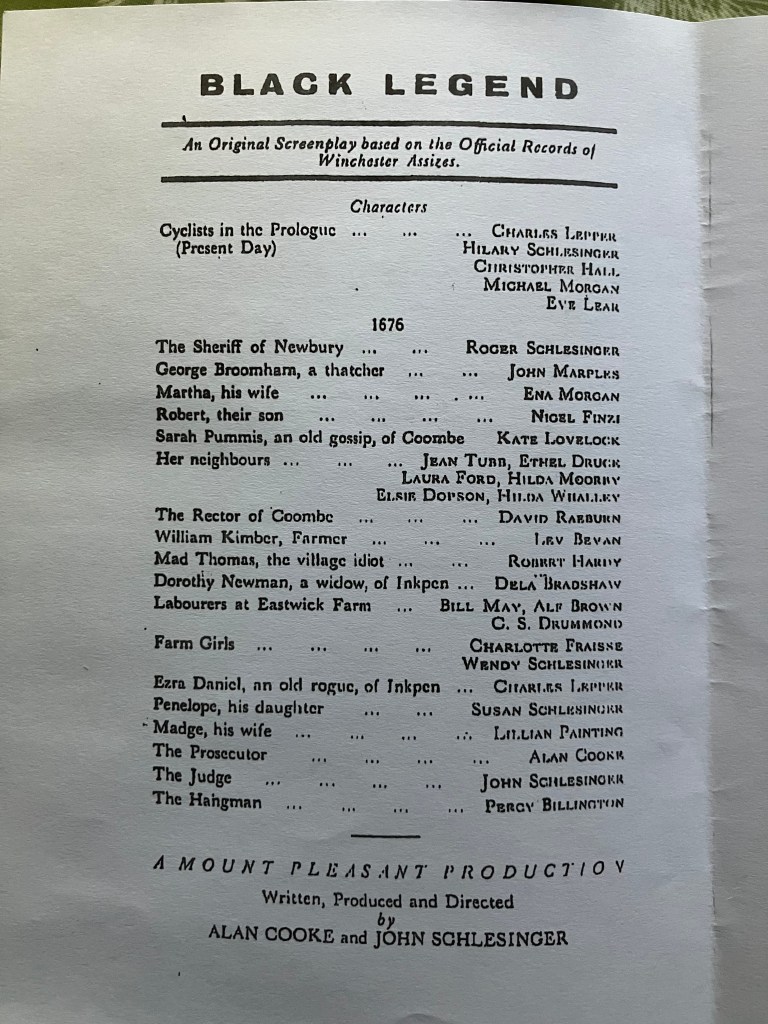

Entitled, Black Legend, the film used actors drawn from, variously, members of Oxford University Dramatic Society, one young director’s family who lived locally, villagers from Inkpen & Combe and children from Christchurch School, Kintbury.

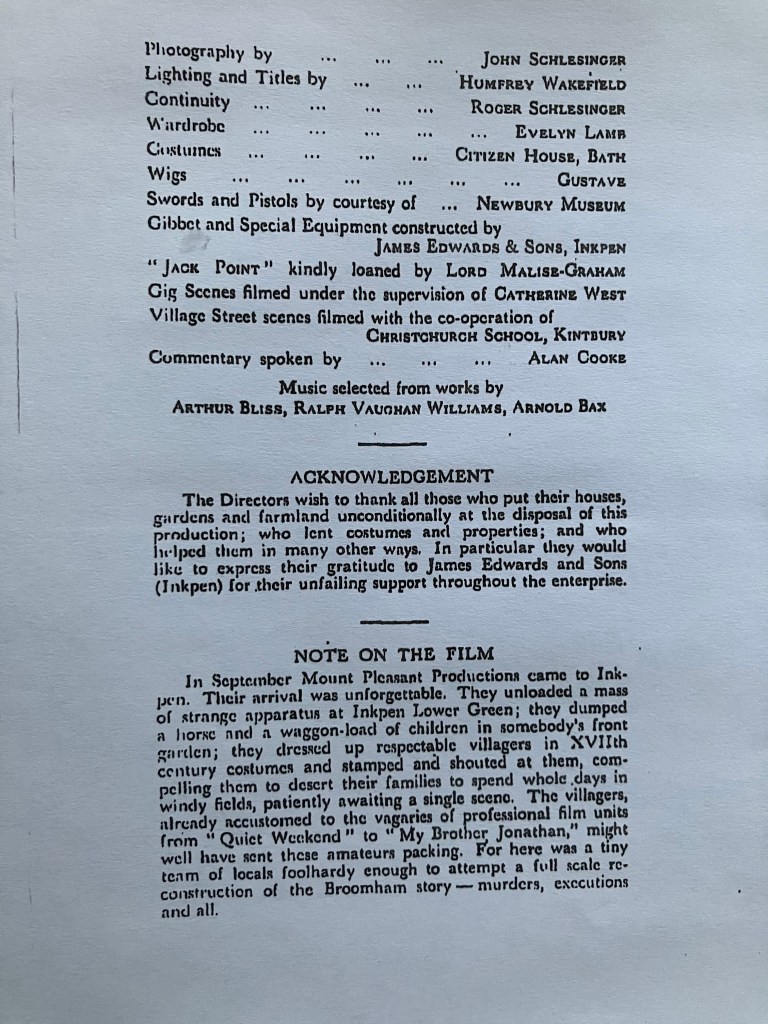

The weather that September was sometimes cold and bleak; shooting was held up when the camera broke and had to be sent away for repairs. However, the young men were pleased with their results, writing in the film’s accompanying programme notes:

But for all its failings we believe BLACK LEGEND to be an achievement that in one respect at least has rarely been equalled. For it shows how much can be achieved by the co-operation of enthusiastic people, even in a project so technical as a film.

Were the young students right to feel so positively about their work? Well, when the finished version was shown – in Hungerford, Inkpen, Ashmansworth and West Woodhay the following January, 1949 – the Newbury Weekly News declared in its advertisement for the screening, “The Film YOU helped to make” and “YOU’LL BE SORRY YOU MISSED IT”.

In its review, the Newbury Weekly News quotes an anonymous film critic as saying:

“Black Legend is a film to see and remember…

The acting is a marvel of cooperation among amateurs, some skilled, some quite inexperienced, but all gifted enough to convey their thoughts and often their probable words without any speech.

Soon, Black Legend was to receive a wider audience than the villages around Newbury. An article in the Scotsman of March 1949 reports that it had been shown in the Grand Committee Room of the House of Commons. The film is now described as, “having all the cinema world by the ears.”

The report goes on to say,

“The wonderful landscape, the local people, the farms and their implements, are all so used … that the compositions are beautifully organised; the photography of these young people with relatively little experience resulting in a work which ought to make the film industry pull up its socks.”

These young men obviously showed promise: but did they fulfil that promise?

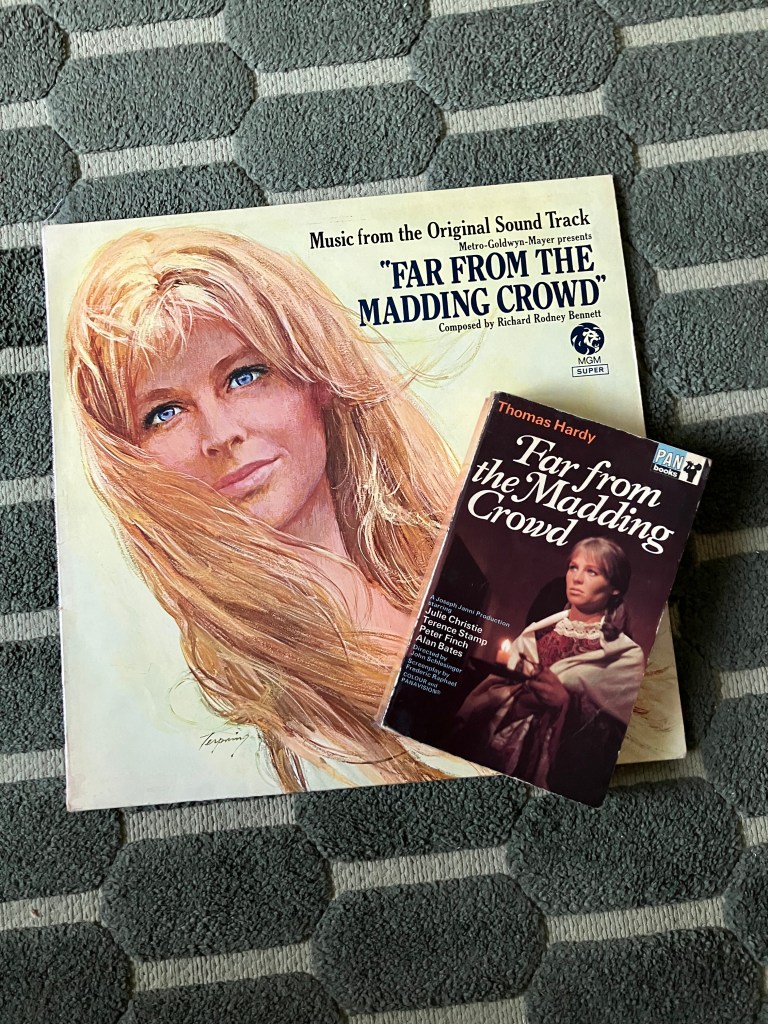

In 1965 one of those young men returned to film on the chalk downland not so very far from here. By now, John Schlessinger – whose family had lived near Kintbury in the 1940s – was regarded as part of the British “New Wave” of film directors and his previous movie, “Darling,” had been Oscar nominated.

This time, Schlessinger’s leading actors were well known throughout the movie world of the early 1960s: Terence Stamp, Alan Bates and Julie Christie, although, as with Black Legend, his cast included many local people. “Far from the madding crowd,” an adaptation of the novel by Thomas Hardy, was to be filmed entirely on location – as Black Legend had been – this time in Wiltshire and Dorset. Just as Black Legend had featured music by Vaughan Williams to compliment the film’s rural setting, so Richard Rodney Bennett’s score for “Far from the madding crowd” is frequently reminiscent of Vaughan Williams’ work, similarly using variations on English folk songs to evoke the period and place of the piece.

Schlessinger’s “Far from the madding crowd” is one of my favourite films. It must be one of the most visually beautiful films ever shot in England and captures the Wessex downland like no other, in my opinion. So many shots, I feel, are reminiscent of scenes in Black Legend, almost as if Schlessinger was finally perfecting, on a much higher budget and in glorious technicolour, scenes he had shot with Alan Cooke on and around Walbury Hill, all those years before.

Throughout his career as a film maker, John Schlessinger received four BAFTAs and an Academy Award (an “Oscar”). He was made a CBE in 1970 and a BAFTA Fellow in 2002.

He died in 2003.

(C) Theresa A. Lock 2024

References:

https://www.bfi.org.uk/features/where-begin-with-john-schlesinger

Newbury Weekly News Archive, West Berkshire Library

British Newspaper Archive