The village Jane knew was, of course, very different from the village we know now. So, what do we know about Kintbury- and the wider world – in Jane Austen’s time?

For much of Jane’s life, England was at war with the French. When Jane was 5 in 1780, the Gordon Riots took place. In 1788 George III’s first illness began and the first convicts were sent to Australia. In 1792, the September massacre took place in France and 12,000 political prisoners were murdered. In 1793 Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette were executed and France declared war on Great Britain. Then, in 1797 the French landed in Wales, – the last invasion of Britain! In 1798 the Battle of the Nile took place.

In 1804 Napoleon had himself crowned Emperor, then 1805 saw the battle of Trafalgar and the death of Nelson. In 1807 the Slave Trade was abolished, 1810 and 11 saw the King’s illness recur and the Regency established. In 1812 Napoleon invaded Russia and America declared war on Great Britain. The war ended in 1814 and 1815 saw the battle of Waterloo and restoration of Louis XVIII to the throne of France.

The 1834 Poor Law Act saw the building of more workhouses throughout the country to house the poor and destitute; one was built in Kintbury.

For cricket fans June, 1814 also saw the first match to be played at Lords.

Jane received letters from her sailor brothers and other relatives and was therefore conversant with European news. In her novels, sailors and soldiers appear but there is never any specific reference to the situation in Europe or to war. Similarly, life in inland villages such as Kintbury would have been lived with far less reference to the turmoil across the channel and the fear of invasion than that which threatened some coastal areas during the war with France.

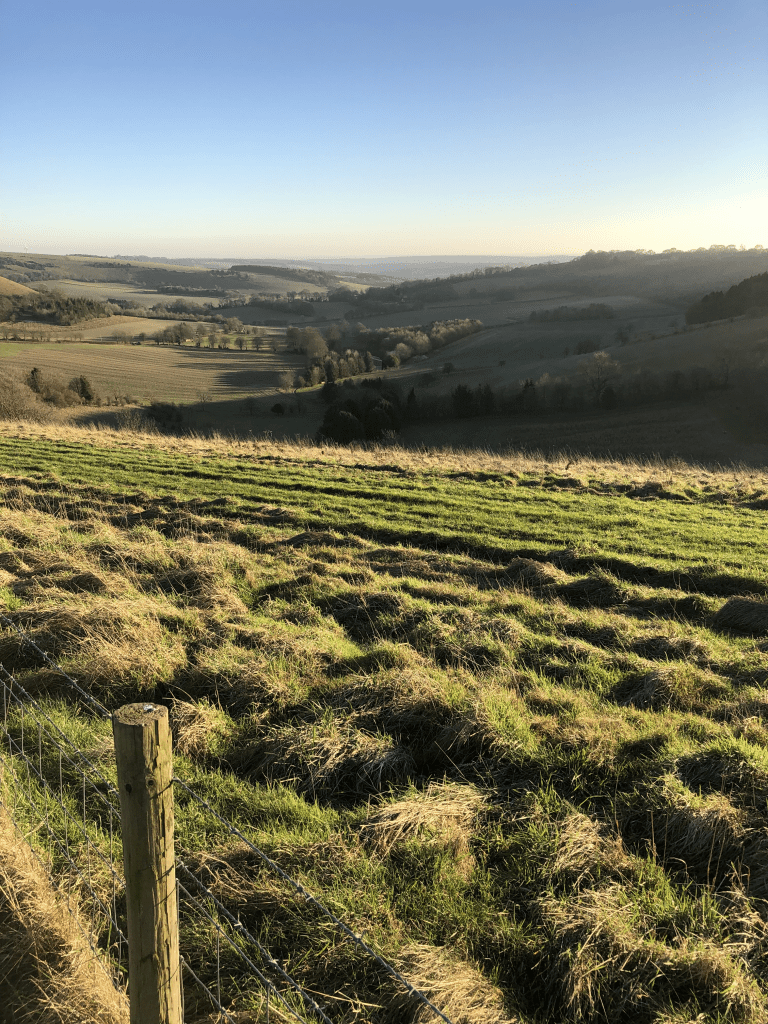

The Kintbury Jane knew was much smaller than the modern village we know today; most of the housing was located around the centre and surrounded by fields or open land. Dotted around the village were whiting pits as well as pits from which clay for brick making was extracted.

Irish Hill had its own little clutch of cottages which remained until the 20th century. Despite the legend that it was named “Irish Hill” for the Irish navvies who worked on the canal, the original name, which predated the arrival of the canal, was in fact Ayrish Hill. It was the site of yet another of Kintbury’s whiting manufactories and after the canal came into existence had a jetty where the whiting was loaded onto barges.

The Rev’d Thomas Fowle II was vicar of Kintbury from 1762 to 1798. He had been a close friend of Jane Austen’s father George since their days together as students at Oxford University.

In 1775 an alarming event at the Rev’d Mr Fowle’s vicarage was reported in the local papers: on Wednesday 6th September, at about nine of the evening, a ball of fire entered the house at one of the garrets which went through the house, melted the bell wires, threw two candlesticks from the table, entered a cupboard and set fire to some papers. The family were much alarmed but no further injury sustained.

Also in June 1775, the paper reported that smallpox had broken out and was likely to increase. It was advisable to inoculate the poor and as the situation was very hazardous people were advised not to visit the area. This is the attack in which the Lloyd family at nearby Enborne suffered. At this time, Martha – who was later to become Jane’s close friend – was 10, Eliza – later to be Mrs Fulwar Fowle – was 8, and their sister Mary,4. Sadly their brother, Charles, aged 7, died.

In 1779 Jeff Painter, an old parish pauper, was found dead and Mrs Giles, in a despondent state, cast herself into a well. The Jury’s verdict on this last was ‘lunacy’.

One notable Kintbury resident at this time was Samuel Dixon, a barrister at Lincoln’s Inn, who lived with his sister in Wallingtons, (now St Cassian’s Centre), Kintbury. One night in early 1784, when Dixon was staying in London, his butler, a man called Benjamin Griffiths, broke into Wallingtons, stealing several items and setting fire to the house which was burnt to the ground.

At first, Griffiths was not suspected of being the arsonist and, ironically, he was sent to inform Dixon of what had happened. However, his behaviour aroused suspicion. When charged he confessed and cut his throat but recovered, was convicted and hanged.

Griffiths had previously been a toll gate keeper and was suspected of murdering his partner although never convicted of the crime. There were, according to Newbury historian Walter Money, three toll gates between Newbury and Marlborough and Dixon was on the board of The Turnpike Trust which might go some way to explain why he later employed Griffith. Dixon tried, unsuccessfully, to get the death sentence commuted. In his will left money to two of Griffiths’ children.

Samuel Dixon died in 1892. His sister Elizabeth had predeceased him in 1786 and he had carried out her wishes in providing the parish with a ‘good fire engine’ which is now in the Newbury museum.

Arson was not the only crime to be committed by a resident of Georgian Kintbury.

In October 1785, Charles Smart was transported for seven years for stealing wheat from Mr. Barker. Then, in July, 1787, Thomas Page was sentenced to be kept for three months hard labour in the House of Correction for leaving his family chargeable to the parish.

Also in 1785, an advertisement appeared in a local paper for a Kintbury School for Young Gentlemen. It stated that the young gentlemen were to be carefully instructed in language according to the principles of grammar. The charges for boarders at this school were:

- Boys under twelve: 12 guineas

- Boys 12-13: 14 guineas

- Over 14: 16 guineas.

If the boys were kept at school over the Christmas and midsummer periods then the charge was 1 guinea.

In January, 1790, Thomas Hillin was committed to the county Bridewell charged on the oath of James Thatcher, surgeon of Hungerford, with attempting to extort money by threatening to charge him with a detestable crime! However, what, exactly, the detestable crime was, we do not know!

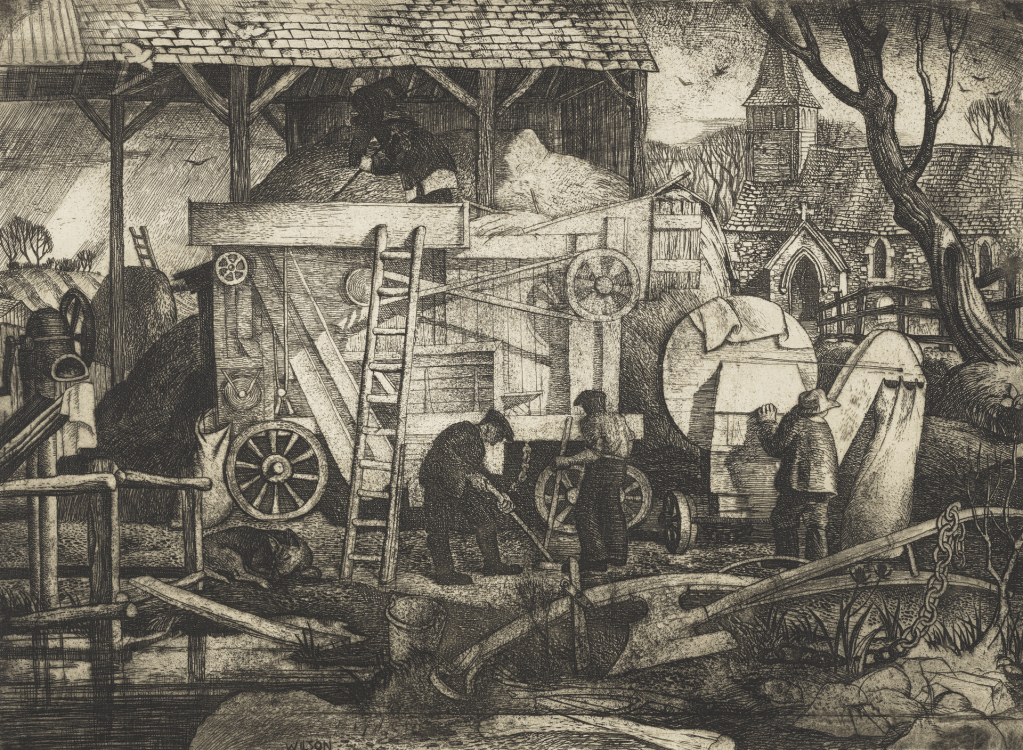

A village woollen manufactory was advertised in July 1797 as containing: “scribbling, raising, shearing etc in a high state of perfection, erected in a commodious building with 40 looms, twisting mill and other articles used in making cloth. A Dye House with every fixture for washing and dying and land surrounding the manufactory desirable and situated with ample supply of water and built to command ever benefit of light and air.”

This must have employed a number of people.

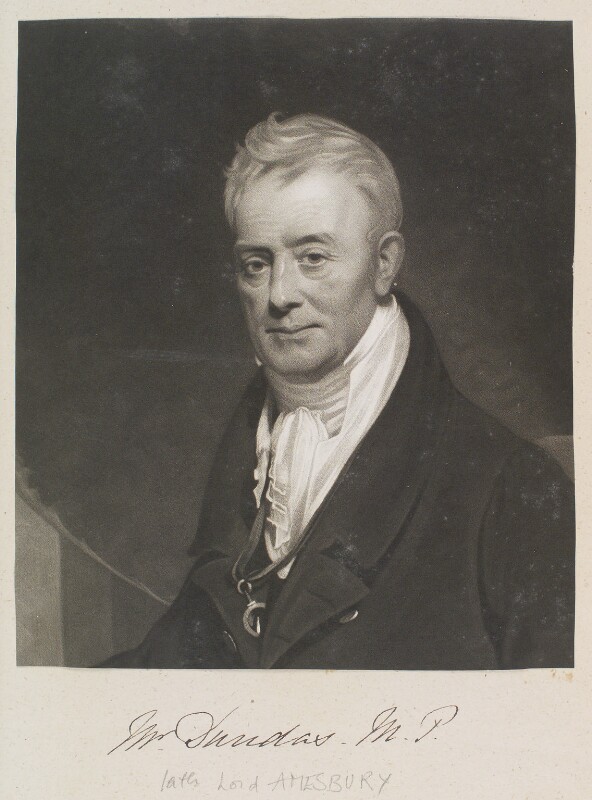

There was also a silk manufactory said to be situated behind the cottages on The Cliffs. Perhaps this was why local resident and MP Charles Dundas raised the question in the House concerning imports of French silk which were ruining the English silk trade.

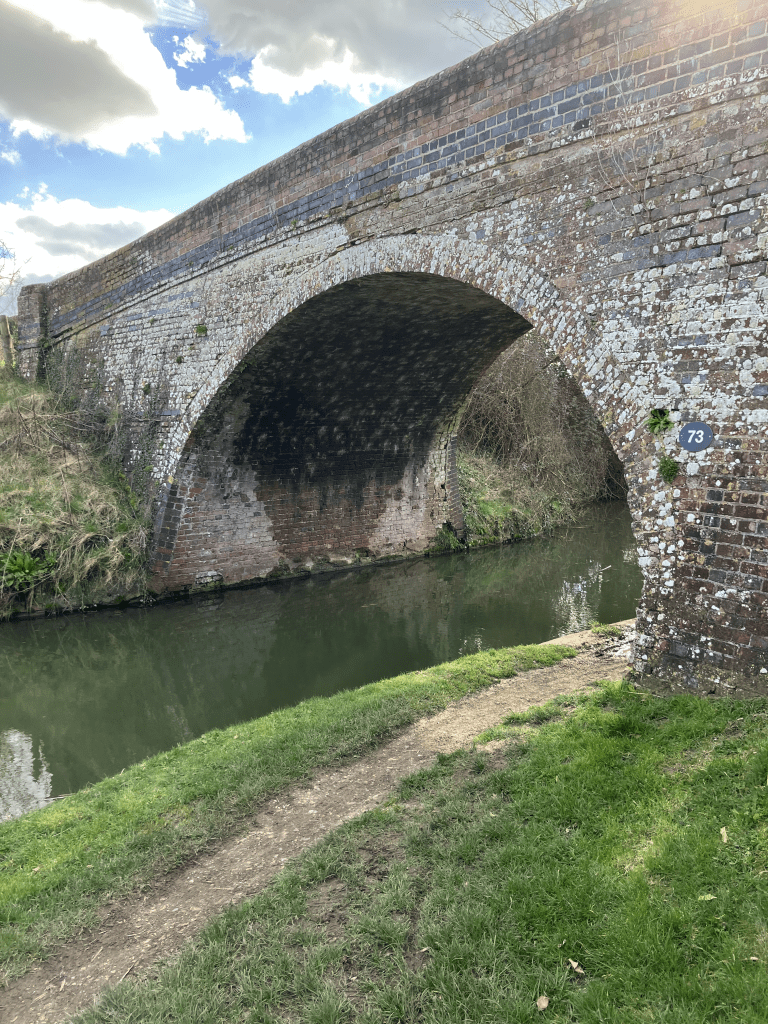

1797 saw the completion of the canal from Newbury to Kintbury. A wharf was built opposite the Red Lion and a busy trade soon developed in all sorts of goods but also it aided the increasingly productive Whiting Industry. The inaugural voyage consisted of a horse drawn barge carrying the band of the 15th Dragoons and several important dignitaries. They were watched by large crowds, reached Kintbury in two hours and dined with the Canal’s Chairman Charles Dundas before setting back to Newbury in the rain.

A crime particularly associated, in the popular imagination, with the Georgian period must surely be highway robbery and it is not surprising that there was at least one example of this crime recorded in Kintbury. In March 1798. John Williams alias Timms and John Davis alias William Emmery held up the Hon Hugh Lindsay and Robert Spottiswood on the highway in the parish of Kintbury. The gentlemen were relieved of money, banknotes and a gold watch.

Daniel Heath is mentioned as innkeeper for the Blue Ball; He was still there in 1830 when, it was said, Prize Fights took place at the back of the inn. Prize fights were a popular sport in Regency times and mostly took place outside cities and towns and their location kept secret. This was the age of Tom Crib famous for his victory over the American Tom Molyneaux and Gentleman John Jackson, the English Champion, both of whom taught boxing to gentlemen.

A more peaceful pursuit was the annual was the Pink Show which began in 1778. Silver plate was presented as a prize and a dinner was held in the Blue Ball.

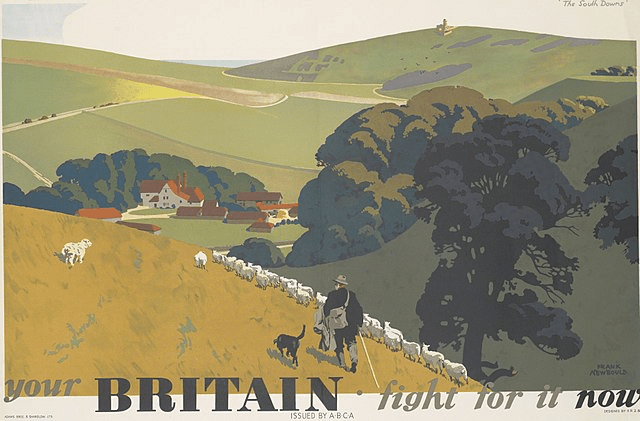

The Napoleonic Wars formed the background of most of Jane’s life and in March 1794 a call had been sent out to the Lords Lieutenants of the counties to form infantry and yeomanry to defend their local areas.

Here in Kintbury, the Kintbury Volunteer Rifles played their part in preparing to defend England if needed.

Particular friends of both Jane and Cassandra Austen were the Rev’d Fulwar Craven Fowle and his wife, Eliza. Fulwar was the son of Rev’d Thomas Fowle II and had taken over the living in Kintbury in 1798.

In 1805, Fulwar led the local Volunteer Brigade to Bulmersh near Reading where they and the other Berkshire Volunteer Regiments were inspected by none other than King George III himself. According to a contemporary report, the troops were on parade at 10.00am and at 2pm the king and Royal Family arrived and then His Majesty rode down the lines whilst the band played a lively air. Afterwards His Majesty expressly desired the Duke of Cambridge to communicate to the Commanders, the particular gratification he felt at having witnessed the military perfection of his Berkshire Volunteers. The King, according to one source, told Fulwar that he knew he was a good clergyman and a good man, now he knew that he was a good officer. Praise indeed!

As well as having an active interest in the military, Fulwar Craven Fowle also had an interest in the developing science of agriculture, keeping his own prize winning flock of sheep. In 1808 two dogs worried his valuable Leicestershire sheep, eleven of which died. It is to be lamented, said the report, that individuals are not careful in securing their dogs as a disaster of this kind is a very serious injury in this most valuable flock in the county.

Unsurprisingly, theft continued to be a problem in Kintbury. In May 1815, someone entered the house of Fulwar Craven Fowle and stole the silver cutlery which had a crest of an arm holding a battleaxe surmounted by a ducal coronet. Silversmiths and pawnbrokers were asked to look out for it and £20 reward offered.

Then, in 1817, John Cozens had a dark bay gelding stolen from the stables opposite the Red Lion and offered £5 reward. Seemingly he could not offer as much as Fowle had following the theft of his silver.

Throughout this period, populations of towns and villages were growing throughout England and Kintbury was no exception. During the years 1761-1815 its population rose from 1,170 to 1,430.

The marriage registers show that, although many people chose local partners i.e. from Inkpen, Kintbury, Hungerford etc some brides chose their husbands from further afield: Binfield, Basingstoke, Marlborough and even Crewkerne. Similarly, brides appeared from Salisbury, Ramsbury, Chieveley, Farnborough and Hurstbourne. Of the grooms, 42% were able to sign their names and 34% of the brides, which suggests quite a high level of literacy at a time when very few people were able to have received an education.

Between the years 1761 and 1812 the average number of births per year was 42 –with an average of 7.2% being illegitimate. Some of the mothers appear to have been in long standing relationships such as Ann Palmer who had five children surnamed Mason. Ann Darling had seven children of whom only one had a surname. Sadly Ann later appears in the workhouse records.

When Ann Green had her baby baptised the vicar wrote disapprovingly that, ’her husband had been transported some years’.

When Elizabeth Harrison brought her son James for baptism it was noted that ‘her husband has been beyond seas for two years’.

Fathers could be summoned to pay for illegitimate children. The father of Elizabeth Watts’ son had to pay £1 towards the ‘lying in’ and one penny a week for the maintenance and twenty pence weekly as long as the child was chargeable to the parish. Elizabeth had to pay or cause to be paid six pence a week. However, Mark Bird from Welford – the father of Esther Sawyer’s daughter – had to pay 40/- for the lying in and £4 19s 6d for maintenance . Esther had to pay 6d weekly.

Although the first census in England and Wales took place in 1801, its results were recorded numerically and it was not until 1841 that we begin to have a clearer idea of trades and occupations in each town or village. However, a study of the church baptismal records give us some idea of how early nineteenth century Kintburians made a living.

In 1813 the church baptismal records began to record the father’s profession and from these we are able to see that the village provided the following:

- 3 shopkeepers

- 1 gamekeeper

- 4 wheelwrights

- 4 blacksmiths 1 of them at Elcot

- 3 cordwainers

- 1 shoemaker

- 4 sawyers

- 1 yeoman who was Bailiff to Charles Duindas

- 4 other yeoman: 1 at Clapton, 1 at Elcot and 1 at Walcot

- 6 carpenters

- 1 coachmaker

- 1 publican

- 2 bakers

- 1 miller

- 1 thatcher

- 3 farmers

- 1 pig dealer

- 1 maltster

- 1 grinder at mill

- 1 tanner

- 2 gentlemen identified as “Esquire”

- 1 clerk in holy orders at Barton Court.

However, the majority of fathers were listed as labourers and these numbered around 80. Of course, these were only those men who had brought their children for baptism in the years 1813-1817.

Today Kintbury could be regarded as a dormitory village and a great majority of residents are employed outside the village. The Kintbury known to Jane Austen must have been a busy, vibrant place largely supporting its own community.

Penelope Fletcher ©2024