Cassandra Austen had one love in her life: Kintbury’s Thomas Fowle. Following his untimely death, it seems she forsook all others and remained single for the rest of her life.

So who was Thomas Fowle?

We do not know what he looked like – perhaps we have an image in our minds of the stereotypical late eighteenth century curate – perhaps that image is a sort of caricature.

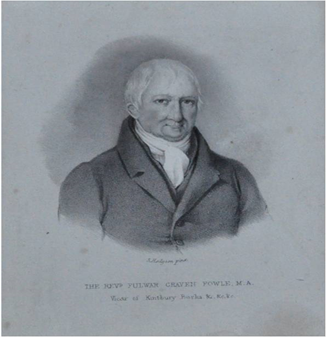

If Tom looked anything like his grandmother, his uncle or indeed his older brother Fulwar, he would have had a long nose and a very defined chin. Fulwar, we know, was not particularly tall.

So perhaps Tom did not look like a young Colin Firth as Mr Darcy – or indeed any one else as Mr Darcy. Neither was Tom the heir to a Pemberley, in fact he was heir to very little at all. But Cassandra loved him and she must have loved him for who he was.

We know that Tom was born in Kintbury in 1765 and was the second son of the parish priest, also named Thomas.

These were the days of patronage and preferment and holding the living at Kintbury had become something of a family business because Thomas’s grandfather, another Thomas, had become vicar in 1741. So the Fowles were the vicarage family in this quiet backwater – all very rural, and, it is easy to imagine, all very sedate and proper.

However, on Thomas’s mother’s side, things had been a little bit different.

Thomas’s maternal grandfather was the Honorable Charles Craven who, between 1712 and 1716, had been the governor of South Carolina. He seems to have been something of a man of action and in 1715 actually led an army of colonists and their native American allies in a war against other native American tribes who, one presumes, saw the colonisation of their country differently.

Charles’s son, Thomas’s cousin John, seems to have been a man of action but in a very different way. He took holy orders and by the 1770s was appointed to the parish of Wolverton in Hampshire although it seems he was living at Barton Court in Kintbury at this time. If there had been a tabloid press back then, John Craven would have been a favourite for supplying sensational copy with an incident involving pistols at a hotel in Wantage and a very lurid divorce case in which maids testified at having heard the sound of beds springs coming from a lady’s room John had recently entered.

Thomas’s grandmother, Elizabeth Craven, was, we believe, something of a socialite. Her bust, now in the north transept at St Mary’s church, Kintbury, is part of the very elaborate and – when it was new – eye-wateringly expensive monument to her second husband, Jemmet Raymond. The representation of Elizabeth, presumably based on a portrait now long lost, shows face with a very stern expression.

Elizabeth Craven is believed to have had a difficult relationship with her daughters. One is said to have eloped with a horse dealer and another, Martha, left home to work as a seemstress under an assumed name to hide her identity. Eventually she married the Rev Noyes Lloyd of Enborne near Kintbury and became the mother of Eliza, Martha and Mary Lloyd. Jane Craven married Thomas Fowle II of Kintbury and became the mother of Thomas and his brothers, Fulwar-Craven, William and Charles.

However, the Craven relation who would have the most devastating influence on Thomas’s life has to be his cousin, William Craven, 1st Earl of Craven of the 2nd creation – to give him his full title – and the son of one of the richest men in England. Other people choose to remember him as the man who kept his mistress Harriet Wilson at Ashdown House.

One wonders what the family at Kintbury would have thought of those Craven relations – what would Thomas and his brothers have told Jane and Cassandra of their grandmother, whose memorial back then would have been to one side of the altar and therefore much more prominent? Perhaps they would have enjoyed the gossip value and agreed with Mr Bennet that we exist to make sport for our neighbours and laugh at them in our turn.

But nothing sensational or scandalous ever attached itself to the Fowles in their Kintbury vicarage. Being related to members of the extremely wealthy Craven family, was, I suppose, an advantage for both the Fowles at Kintbury and the Lloyds at Enborne since this was still the time when members of the aristocracy and more influential gentry could appoint vicars to parishes within their gift. However, having a grandfather who was an honourable and a cousin who was an earl did not mean the Fowles or the Lloyds moved easily in similar social circles. The Fowles were not wealthy. Thomas Fowle II did not send his sons to a public (expensive fee-paying) school such as those at Winchester, Harrow or Eton. Instead Fulwar, Thomas, William and Charles were sent to the vicarage at Steventon in Hampshire to be educated by their father’s friend from university days, Rev George Austen.

Thomas Fowle was 14 in 1779 when he was sent to study at Steventon, presumably with the intention that George Austen’s teaching would prepare him for a place at Oxford University. Fulwar had taken his place at the vicarage school in the previous year and it is not surprising that the Kintbury boys became close friends with the Austens of the same age, in particular with James. Cassandra was just six when Tom arrived at Steventon and ten when he left to take up his place at St John’s College, Oxford.

Home theatricals were a popular past time at Steventon and in December 1782 the young Austens, along with some of their father’s pupils, staged their own production of a contemporary play, “The tragedy of Matilda” by James Francklin. James Austen wrote a prologue for the play, which was spoken by his brother Edward, and an epilogue which was spoken by Tom Fowle. For the nine year old Cassandra, the Fowle boys must have seemed as familiar as her own brothers and it is easy to imagine how her relationship with Tom grew in the creative atmosphere of the Steventon vicarage.

The following year, 1783, Tom went up to Oxford, where he graduated with a BA from St John’s college in 1787 and then taking Holy Orders. He became curate of East Woodhay – not far from Kintbury – in 1788 and also, in the manner of the time, at another parish, Welford, also not far from Kintbury.

We know that on at least on two occasions, Tom officiated at weddings at George Austen’s church in Steventon, one in 1789 and another in December 1792. On this occasion the marriage was between Mrs Austen’s niece, Jane Cooper and one Thomas Williams Esq. Both of her parents having died, Jane was being married from the home of her aunt and uncle, with George Austen taking the place of her father, I presume, and therefore unable to officiate. I think it says something of the relationship between the Austens and the Fowles that Tom stands in for Rev Austen to officiate at this wedding rather than a local curate.

Although Cassandra was only ten when Thomas left Steventon for Oxford, we know that in later years various members of the Austen family visited their friends at the Kintbury vicarage. In a poem written at Kintbury in 1812, James Austen, who was a particular friend of Tom’s elder brother, Fulwar, recalls his visit to Kintbury in the early 1780s:

“ Yes, full thirty years have passed away,

Fresh in my memory still appears the day

When first I trod this hospitable ground…”

James recalls with affection, Jane & Thomas Fowle:

“ The father grave; yet oft with humour dry,

Producing the quaint jest or shrewd reply,

The busy bustling mother who like Eve,

Would ever and anon the circle leave

Her mind on hospitable thoughts intent.”

James Austen’s poem creates an image of a warm and welcoming family with a sense of humour, not unlike the impression we get of the Austen family themselves.

The poem has some very sad lines as James recalls Cassandra’s betrothal to Tom:

“Our friendship soon had known a dearer tie

Than friendship self could ever yet supply,

And I had lived with confidence to join

A much loved sister’s trembling hand to thine.”

In 1788, Fulwar had married his cousin, Eliza Lloyd, whose sisters, Mary and Martha Lloyd were to become close friends with Jane and Cassandra. In 1797, Mary Lloyd became James Austen’s second wife. They had first met in Kintbury.

So this was the extended family circle Cassandra anticipated joining when she quietly became engaged to Tom in 1795. By this time she was 22 and he was 29 and for two years had been rector at the church of St John the Baptist in Allington near Salisbury in Wiltshire.

Family connections had given Tom the post as Allington was one of the parishes in the gift of his cousin, Lord Craven. However, the stripend Tom received from his position here was not enough to support a wife. But Lord Craven had another parish in mind for Tom, however, in Shropshire, and it seems to have been confidently expected that Shropshire was where Tom and Cassandra would be living after their wedding.

But sadly, that wedding never happened.

In 1793, Britain was at war with France. Both countries had interests in the West Indies which resulted in the conflict spreading beyond Europe and across the Atlantic. In 1795, General Sir Ralph Abercrombie was to lead a 19,000 strong expeditionary force to the West Indies. Their number included the Third Regiment of Foot whose colonelcy had recently been bought by Tom’s cousin, Lord Craven.

It is believed that Craven did not know of Tom’s engagement when he asked his cousin to accompany the troops as Regimental Chaplain, and if he had known, would not have suggested Tom should join the expedition. It is possible that Cassandra herself had forbidden Tom from mentioning it. Tom accepted the post and hurriedly made his will on 10th October. It was not witnessed, which suggests, I think, the haste in which it was completed and also perhaps the secrecy of the engagement.

Was it simply that Tom was hoping to raise enough money for him and Cassandra to live comfortably after their wedding that made this young priest accept the post? Was it that he felt he could not say no to his illustrious cousin? Tom would not be the first member of his family to make the Atlantic crossing – his grandfather had been governor of South Carolina, after all. But the journey to the West Indies was well known as potentially dangerous.

In the late autumn of 1795, Cassandra came to Kintbury to take her leave of Tom. Abercrombie’s expedition was delayed by the lack of men and equipment, but eventually sailed from Portsmouth, Hampshire, in November although bad weather in the channel caused further delays to the fleet. It seems likely that Cassandra was staying with the Fowles throughout this time.

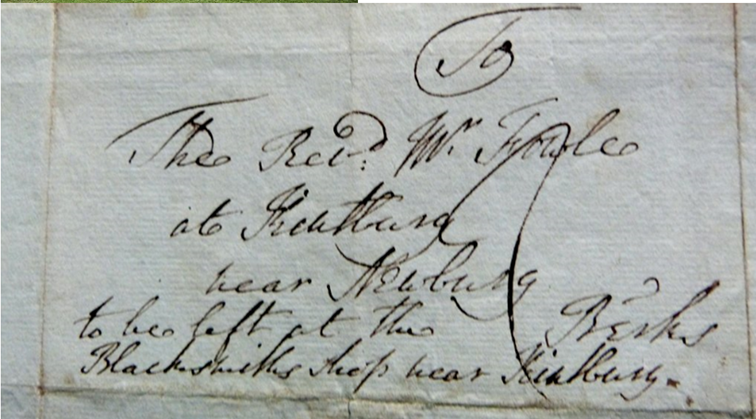

“What a funny name Tom has got for his vessel”, Jane wrote to Cassandra on January 9th, “But he has no taste in names, as we well know, and I dare say he christened it himself.”

Then on the 15th she wrote,

“I am very glad to find from Mary that Mr & Mrs Fowle are pleased with you. I hope you will continue to give satisfaction.”

This must have been a horrible time for Cassandra ; Jane’s apparently light-hearted humour must be seen as a way of coping with a very stressful situation.

Jane had received a letter from Tom anticipating the fleet’s departure from the Devonshire port of Falmouth, which eventually happened on January 10th 1796. “By this time…they are at Barbadoes, I suppose, ” Jane wrote to Cassandra, though, of course, there would be no way of knowing that for sure.

Sadly, Cassandra would never see her Tom again. He died of yellow fever on 13th February 1797 in San Domingo and was buried at sea. Cassandra and the Fowles were expecting to hear of Tom’s return to England; instead, sometime during April they received the news of his death.

We can presume that it would have been Tom’s parents, Thomas & Jane, who would receive the news first. But it fell to James Austen and his new wife, Mary Lloyd Austen, to break it to Cassandra that Tom would never return. We can only imagine what shock waves this awful news must have sent through the now extended families of Austens, Fowles and Lloyds. According to Jane, Cassandra behaved with, “a degree of resolution and propriety which no common mind could evince in so trying a situation.”

Because Tom’s will had not been witnessed, his brothers Fulwar and William were required to swear to its veracity, which they did on May 10th 1797. He had left £1,000 to Cassandra, which, whilst not a fortune, was, when carefully invested, a very useful sum.

Tom’s death, however, was not the end of Cassandra’s relationship with the Fowles. As with Persuasion’s Captain Benwick and the family of the deceased Fanny Harville, it seems as if Cassandra’s relationship with the Fowles grew even stronger following Tom’s death and Cassandra continued to visit Kintbury.

As we know, Cassandra never married but shared her life with her sister Jane and their friend Martha Lloyd. Martha, of course, was the sister of Eliza Fowle who continued to live in the vicarage at Kintbury until her death in 1839. We know from Jane’s surviving letters and other sources that the Austens, the Fowles and the Lloyds continued to exchange visits and letters.

We know that Cassandra accompanied Jane on her last visit to Kintbury in early June of 1816. That was the occasion recalled by Mary Jane Dexter, Fulwar & Eliza’s daughter, when Jane seemed to be revisiting her old haunts as if she did not expect to see them again.

So was the visit in 1816 Kintbury’s last link with Cassandra? I think not.

Fulwar Craven Fowle’s daughters, Mary Jane, Elizabeth Caroline and Isabella had, as children, all known both Jane and Cassandra. Mary Jane married Lieutenant Christopher Dexter and lived with him some time in India. She was widowed at 31 and returned to Kintbury where she died in 1883. Isabella married a local doctor, John Lidderdale, and also lived in Kintbury until her death in 1884.

That leaves Elizabeth Caroline, the daughter who had been christened by James Austen in 1799 and described by Jane in 1801 as “a really pretty child. She is still very shy & does not talk much.”

Elizabeth Caroline Fowle never married but, like her sisters, continued to live in Kintbury. When Cassandra Austen died in March 1845, she left Elizabeth Caroline £1,000 – exactly the sum left to her by Tom – and a large Indian shawl that had once belonged to Mrs Jane Fowle, Tom’s mother.

Quite why Elizabeth Caroline should be the only member of the Fowle family to be a beneficiary of Cassandra’s will, I have not been able to find out. Perhaps, as the one Fowle sister who never married, Cassandra felt some fellow-feeling for her – maybe Elizabeth Caroline had suffered a disappointment such as Cassandra had when Tom died. Also, there is evidence to suggest that Elizabeth Caroline was not quite so well off as her sisters. Perhaps, as James Austen had baptised Elizabeth Caroline, Cassandra had stood as one of her godparents – I do not know. In 1860, Elizabeth Caroline Fowle died, having spent the last six months of her life, not in Kintbury, but as a private patient at an asylum in London.

In 1860 the old vicarage – the home to three generations of the Fowle family, the place where James Austen first met Mary Lloyd and where Cassandra had said her last goodbye to Tom – was pulled down to be replaced by a house in the very latest Victorian neo-Gothic style.

To this day, there are houses in Kintbury where, it is sometimes claimed, Jane Austen stayed. I believe that the only house about which we can say for sure, “Jane Austen stayed here” was the original vicarage on the banks of the canal, now long gone and replaced. Cassandra may well have continued to visit Rev Fuller and his wife Eliza there after Jane’s death. However, with regards to the other houses, I believe that it has to be likely that these were the homes of Elizabeth Caroline, Mary or Isabella and that Cassandra would have stayed with with one of them on her later visits to Kintbury. It has to be very likely that, over the years, local folk memory has somehow become confused. So, when Kintbury villagers knowingly talked to their children and grandchildren of the illustrious visitors who once stayed here, the Miss Austen of whom they spoke so respectfully was not Jane, but Cassandra.

(C) Theresa Lock 2025