The trial begins

The Berkshire Chronicle reported that the majority were charged with “ riotously assembling and destroying threshing machines and other species of property.” These “outrages” were “accompanied by robberies of money and in a fewer number of instances, provisions were forcibly demanded and obtained.”

The report goes on to say that only 25 of the prisoners could read and write, 37 could read only and the remainder could neither read nor write. (This is not surprising considering that no formal education would have been available to them.)

On Tuesday 28th December, William Oakley, William Smith alias Winterbourne, Daniel Bates and Edmund Steel were placed at the bar, charged with robbing John Willes, Esq of five sovereigns on 22nd November in Hungerford, and also of riot, further robbery and destroying machinery. (Presumably, robbing a gentleman of five shillings was considered to be a more serious crime than the rioting and destroying machinery.) None of the men were themselves agricultural labourers. Oakley was described as being about 25 and “better dressed than is usual among members of the class of working tradesmen.”

The Berkshire Chronicle’s journalist clearly felt no need to avoid subjectivity or bias in his reporting, stating that Oakley was, “a pale sinister-looking person, as is Winterbourne.” Winterbourne was 33 but looked older. Bates was described as having, “an extremely mild, good natured expression of countenance”, whilst Steele was a “determined looking man”. Winterbourne was the only one of the four who could neither read nor write, being described as, “entirely uneducated”.

John Hill of Standon House, Hungerford, was quoted at length. He recounted that on 22nd of November he was in the company of 11 or 12 others intending to prevent the “Kintbury mob” from approaching Mr Cherry’s house (Denford House). They met the mob, which apparently consisted of 200 to 300 men, on the Bath Road. “Some of them had large stakes and sticks in their hands.”

The mob proceeded to Hungerford where they broke windows in Mr Annings’ house. Next they broke into Mr Gibbons’ foundry. Mr Willes, Mr Pearse and others then went to the Town Hall where they met with five “deputies” from the Hungerford mob and five from the Kintbury mob. Winterbourne, Oakley, Bates and Steele were four of the Kintbury deputies and were present when the Hungerford deputies demanded 12 shillings a week wages, the destruction of the threshing machines and a reduction in house rent. Mr Pearce agreed that wages should be raised though he was not able to say anything about the rent.

Next the Kintbury deputies spoke and according to John Hill, Oakley said, “You have had a parcel of flats to deal with, but we are not to be so easily caught”. He demanded £5. Then Bates allegedly flourished a sledge hammer and, striking it on the ground, said, “We will be d—– if we don’t have the £5 or blood”.

Apparently, other witnesses could recall more of what was said: Mr Joseph Atherton recalled Oakley as having added, “We will have 2 shillings a day till Lady day and half a crown afterwards for labourers, and 3 shillings and six pence for tradesmen. And, as we are here, we will have £5 before we leave the place or we will smash it.”

According to Atherton, many of the men were armed with bludgeons, sledge hammers and iron bars.

Oakley is reported as having then addressed himself to Mr Pearce: “You gentlemen have been living long enough on the good things; now it is our time, and we will have them. You gentlemen would not speak to us now, only you are afraid and intimidated.”

Until this point there is no account of Winterbourne having spoken but then someone called Osbourne is alleged to have put a hand on his shoulder, to which he replied, “If any man put his hand upon me, I will knock him down or split his skull”.

Atherton alleged that Winterbourne was carrying an iron bar, three or four feet long in his hand, whilst Oakley had an iron bar, Bates a sledge hammer and Steel a stick.

According to the witness, Winterbourne said to Bates, “ Brother, we have lived together and we will die together” and this was the point at which Bates struck the sledge hammer hard on the floor, saying, “Yes, we will have it or we will have blood and down with the b—–y place”.

According to Atherton, this was the point at which Bates flourished the sledge hammer over the head of Mr Willes who responded with. “If you kill me you only shorten the days of an old man”. Mr Willes then gave five sovereigns to the prisoners, who left.

A third witness, Mr Stephen Major, recalled Mr Willes as requesting the men to leave their weapons outside the door, but that Oakley replied, “I’ll see you d—- first”. Then he said, “Here are only five of us, but we can soon clear the room.”

The final witness whose evidence was reported, was Willes – a magistrate – himself. Willes recalled meeting with the mob on their way to Mr Cherry’s house (Denford House, on the Bath Road). He asked the men not to go to Denford House but to follow him to Hungerford Town Hall where, if they were reasonable, he would hear their grievances. He recalled trying to stop the men from breaking Mr Annings’ windows and attacking Mr Gibbons’ manufactory but without success.

Willes believed that the combined Hungerford and Kintbury mob numbered 400 and it was his request that five members from each village should come into the town hall. He alleged that the men said that they never would have come there but for he who enticed them and that they would not leave the hall without having money – £5. When he was cross examined, Willes said that the mob treated him kindly and led his horse by the bridle. Observing that Steel had a hatchet in his hand, he said to him, “My friend, that is a lethal weapon you have; it would split a man’s skull”, to which Steel replied, “Depend upon it, sir, it shall never injure yours”.

The next crime for which the men were, variously, charged was that of riotous and tumultuous assembly and destroying certain machinery employed in the manufacture of cast-iron goods. Several machines had been destroyed that night, and demands made for money or “vituals”. This included destroying the threshing machine belonging to Captain Thomas Dunn at Kintbury and also one belonging to Joseph Randall in Hampstead Marshall, where the men also demanded money or food and drink. Elizabeth Randall recalled that one man wielded a sledge hammer, others had sticks. She said that the men referred to William Winterbourne as, “Captain” which would have given the impression that he was a ring leader. He had instructed the men, she said, not to damage the farm house.

Intimidating behaviour?

It is interesting to note that the accounts of witnesses to the events of 22nd November, particularly those in Hungerford Town Hall, describe scenes which are much more intimidating and potentially violent than the impression given by Rev Fowle of his meetings with the men that day. Fowle’s account includes none of the kind of language used by Dundas in his letter to Home Secretary Melbourne of November 24th when he speaks of the, “shameful and outrageous conduct of the labourers”. In describing his meetings with the men, Fowle’s tone would seem to be conciliatory, even sympathetic in an understated way. He is not judgemental and makes no negative or pejorative comments about their behaviour, even though it could not have been pleasant to have been woken up at four in the morning by a band of men intent upon destroying machinery. The men obviously felt he was on their side when they gave him three cheers. All the evidence available would suggest that Fowle has sympathy with the plight of these men – his parishioners.

Sentenced to death

Sympathy, however, seems to have been in short supply as far as the court was concerned. Sentences of imprisonment, transportation and execution were available to the judges at the trials of the 138 West Berkshire men who stood accused and most were given prison sentences or sentenced to transportation of between 7 and 14 years. However, Mr Justice Park passed sentence of death on just three of the men, all of them from Kintbury. These were William Oakley, Alfred Darling and William Winterbourne.

According to the judge, William Oakley had taken an active part in acts of robbery and, in the robbery of Mr Wilkes, had been armed with dangerous weapons, refusing to lay them aside.

Alfred Darling, as a blacksmith, had no right – according to the judge – to be involved with the rioters.

William Winterbourne, he maintained, had taken an alarming part in the outrages as leader of the mob. He had acted as captain of the band, dictated what was to be done and “received money or not according to his will and pleasure.”

Mr Rigby disagrees

Many people disagreed with Mr Justice Park’s sentencing. Mr Rigby, counsel for the defence and the solicitor who had cross examined the men, was quoted in the Reading Mercury of 10th January 1831 as having said:

“It has been said, that some of the persons who perpetrated these outrages were artisans, not agriculturalists, and had not the excuse of poverty or low wages. But surely let those who advance the argument consider. What! has the poor man no feeling of commiseration for his fellow man because he has a loaf on his table for his own wife and family?”

Whilst Rigby’s sympathy and understanding would have been welcomed, there is an irony here in that the pay of artisans – ie tradesmen, for example blacksmiths or carpenters – would not have been high, either.

The Reading Mercury reported that Oakley, Winterbourne and Darling were, “to be executed, the jury having found them guilty of encouraging unlawful meetings of the people, and by intimidation obtaining money from individuals.”

A petition to the King

A petition for mercy was swiftly organised to be sent to the king, William IV. In a day and a half it had collected 15,000 signatures. The ladies of the borough also organised a petition to be sent to Queen Adelaide.

by Sir Martin Archer Shee

oil on canvas, circa 1800

NPG 2199© National Portrait Gallery, London

This was not the only petition: many County & Borough magistrates appealed to the Home Secretary, Lord Melbourne.

“Your petitioners believe….. the offence for which the prisoners have been convicted is one, which in the common opinion of uneducated men, was not considered as capital, and though ignorance of the law may be no legal defence, in all moral feeling it must and ought to have great weight; for it is possible that had these unfortunate persons been apprized of the danger they incurred, they might have stopped short of the violation of that law on account of which they have been doomed to suffer.”

Two of the grand jurors involved with the case, J.B.Monke, Esq and J.Wheble Esq, also appealed to Secretary of State, Lord Melbourne, to petition the King for mercy.

It is interesting to note that, in an age when there were so many laws on the statute books which seem to us today to be biased against the working man and woman and which did nothing but cause them hardship, the imposition of the death penalty in this case caused such strong feelings of objection. Perhaps the case of the rioters, laid out every day in the Reading newspaper reports, had caused members of the middle and upper classes to consider what life was really like for their poorer neighbours.

For Oakley and Darling, the execution of the death sentence was respited (sic) although no such mercy was accorded to Winterbourne.

January 11th 1831

According to the Berkshire Chronicle of 15th January 1831, it was not until the morning of his execution that Winterbourne was told he would be the only man to die. “He expressed himself glad to hear that his companions were spared.” The newspaper goes on to say that Winterbourne’s wife was lying dangerously ill of typhus fever and that one of his last wishes was that she might die before he suffered or that she might not survive to be shocked by the news of his execution.

Winterbourne was led to the scaffold where, “His large muscular form seemed cramped ,- probably from the position of his arms and tightened of the bonds by which he was pinioned. He walked firmly, but his cheek was pallid, his eyes glazed, and the prayers he uttered, though fervently and audibly expressed, came from quivering lips.”

As the prison clock struck twelve on 11th January 1831, Winterbourne was executed.

Return to Kintbury

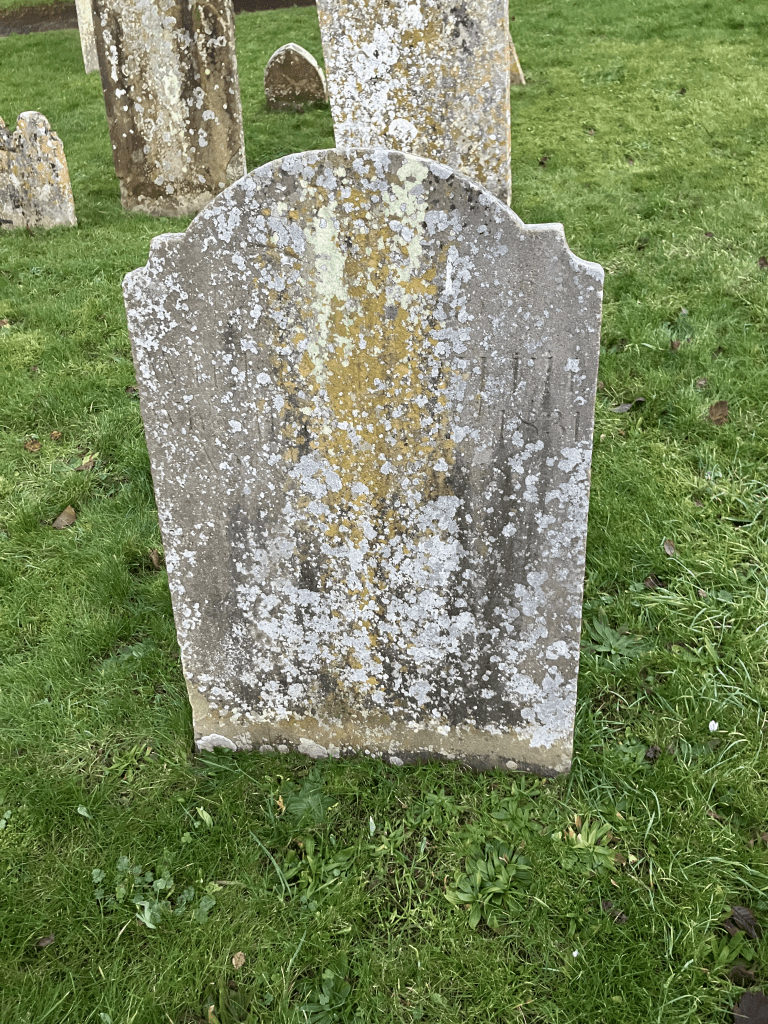

It would have been the custom for the executed prisoners to be buried at Reading Gaol. However, Rev Fowle arranged for Winterbourne’s body to be brought back to Kintbury, where he was buried in St Mary’s churchyard the following, day 12th January. Furthermore, he arranged and paid for a stone to be place on the grave – something that would have been totally beyond the reach of the labouring classes at that time, whose graves would be completely unmarked and grassed over.

According to the custom of the time, the name on the grave stone reads as “William Smith”, Smith being his mother’s name and his parents not being married at the time of his birth. Also, the grave is not tucked away in some far and distant corner of the churchyard, out of sight.

There has been for some time the persistent idea that Rev Fulwar Craven Fowle had Winterbourne’s body returned to Kintbury and the stone erected because he felt in some way guilty about what had happened to him. I have to say that, in researching this, I have found no evidence for this to be the case. The letter written by Fowle to Charles Dundas (now in the National Archives) contains none of the harsh or judgemental language used against the protestors by others. As I have described above, the men gave Fowle three cheers and obviously felt able to tell him of their plans. There is no suggestion that the men arrived at the vicarage armed or that Fowle felt intimidated. All the evidence suggests to me that they expected to be treated fairly by him, and that they were.

It is believed that around 2,000 people were involved in the Swing Riots by the end of 1830. Five hundred were transported and 19 executed. This was four years before the men of Tolpuddle in Dorset were convicted of swearing a secret oath as members of the Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers, and sentenced to transportation. Those involved in the Swing Riots are not as well remembered as the men of Tolpuddle, but they deserve to be remembered too, for their part in the workers’ struggle for a fairer life.

In Kintbury, William Smith, alias Winterbourne, is not forgotten.

Bibliography

Griffin, Emma, (2018), Diets, hunger & living standards during the British industrial revolution, Past & Present.

Lindert & Williamson, (1983), English workers living standards in the industrial revolution, The Economic History Review

Phillips, Daphne (1993), Berkshire: A County history, Newbury: Countryside Books

Thompson, David (1969), England in the nineteenth century, Pelican

Trevelyan, G.M.(1960) Illustrated English Social History:4, Pelican

Woodward, Sir Llewellyn (1962), The Age of Reform, Oxford: OUP

The Berkshire Chronicle (December1830 & January 1831)

The Berkshire Mercury (December 1830 & January 1831)

The National Archives: Letter to Rt Hon Lord Melbourne from Charles Dundas, MP, November 24th 1830

The National Archives: Anonymous letter to Rt Hon Lord Melbourne, November 24th 1830

The National Archives: Letter to Rt Hon Lord Melbourne from Charles Dundas MP & ninety other signatories, November 1830

The National Archives: Letter to Rt Hon Lord Melbourne from Lord Craven, November, 1830

The National Archives: Letter to Rt Hon Lord Melbourne from Rev Fulwar Craven Fowle, November 1830

Theresa A. Lock, Kintbury, October 17th, 2020.

One thought on “The Kintbury Martyr: 3”