The story of Kintbury’s Rev James Whitley Deans Dundas

In 1840, Rev Fulwar Craven Fowle, who had been a close friend of Jane & Cassandra Austen, died aged 76. He had been the third generation of his family to be vicar at Kintbury so his death must have seemed like the end of an era to his parishioners.

One wonders how Kintbury villagers felt when the next person to be appointed to the parish was a much younger man. Twenty eight year old James Whitley Deans Dundas must already have been known to local people, being the son of Admiral James Whitley Deans Dundas, a member of the well-connected and influential family of Barton Court, Kintbury. He held an MA degree from Magdalen College, Cambridge, had been ordained in 1835 and had become vicar of Ramsbury, ten miles away in Wiltshire, in 1839.

Although I have not been able to find James Dundas on the 1841 census, the 1851 census shows that he is still vicar of St Mary’s, Kintbury. He has, living with him in the vicarage, a cook/housekeeper, a kitchen maid and a groom and, although he is married his wife seems to have been absent on the night of the census. Strangely, the 1861 census also records Dundas as being married, yet his wife is absent again and his staff consists of just one waiting maid.

However, this must have been a time of upheaval in the vicarage, for around this time the original building – the one known to Jane and Cassandra Austen – was demolished and a new, large house in the fashionable Neo Gothic style built to replaced it. Quite why James Dundas chose to do this we do not know; perhaps the old house was in a state of poor repair or perhaps he considered it lacked the style and sophistication fitting a person of his status.

It is easy to imagine the new vicarage filled with a large family and ample servants to run it; but that was not the case. The 1871 census reveals that, whilst Dundas maintained a live-in staff of footman, cook, housemaid and groom, the many rooms did not echo to the sound of children or visiting grandchildren, and, although the vicar is still recorded as being married, Mrs Dundas is conspicuous by being absent.

An online search reveals the rather surprising truth.

Sometime in the mid 1830s, James Dundas had entered into a relationship with Olivia Flora Burslem, the daughter of Captain Nathanial Godolphin Burslem of Harwood Lodge, East Woodhay, Hampshire. Olivia had been born while her father was serving in the army in Java, in the East Indies and it is this rather unusual place of birth which makes Olivia easier to trace on census returns.

Olivia’s relationship with Dundas seems to have been a turbulent one almost from the very beginning. Some of the details can be put together from parish records and various newspaper reports covering the proceedings of the Court of Queen’s Bench in July of 1840.

The couple had been married by special licence at East Woodhay, Hampshire, on February 11th 1836. The groom was 23 and the bride 22.

However, by 1837 the couple were living separately.

In 1839, in an attempt to bring about the dissolution of his unhappy marriage, the now Rev Dundas brought a case against a Mr Hoey of Bath, whom he accused of “criminal conversation” with Mrs Dundas. It seems that a witnesses for the prosecution, a waiter and others who worked at the Castle Hotel in Marlborough, described Mr Hoey and Mrs Dundas arriving there and posing as a married couple.

They stayed for two or three days and “had but one bed”.

Although a case had been built against his wife, witnesses for the defence suggested that Dundas had not been as innocent as he had tried to make out.

The court heard how, in 1834, Dundas had become a frequent visitor at the East Woodhay home of Captain Burslem whose daughter, Olivia, was “possessed of great personal attraction.” Dundas claimed there had been a mutual attraction between the young people and that his intentions were honourable. However, during a period towards the end of 1834, Mrs Burslem had become ill and was confined to her bed for some time. During this time, “the plaintiff was base enough to take advantage of the affections of Miss Burslem and to abuse the confidence reposed in him by her family by effecting her ruin.”

On learning that Miss Burslem was pregnant, the report suggests, Dundas abandoned her. It appears that it was “with great difficulty” that Rev Dundas was persuaded to marry Olivia but after Captain Burslem had settled £10,000 on his daughter and Admiral Dundas had settled £5,000 on his son, the wedding finally took place.

The court heard evidence that, from the time of the marriage, Dundas treated his new wife with cruelty and neglect. There was also evidence to suggest that he was violent towards her. It was even suggested that he had somehow encouraged her into relationships with other men to enable the possibility of a divorce under the very restrictive divorce laws of the time..

At the conclusion of the case, the jury’s verdict was: “We think he had morally deserted her”. Dundas was not granted a divorce.

If Olivia Dundas was not living with her husband in Kintbury, where was she? Although I have not been able to find her whereabouts on the 1841 census, other sources, along with cross referencing, do reveal more about her life after her separation from Dundas.

There is evidence to suggest that Flora was in a relationship with a new partner, one Henry Dean and is styling herself as his wife. In polite Victorian society, this would have been frowned upon by those who knew the truth – although it has to be said that there were likely those willing to”turn a blind eye.” At this time, it would have been almost impossible for Flora to obtain a divorce from Dundas so for a woman who had the means and the opportunity to set themselves up in in another relationship far from the prying eyes of her original home, this was likely the only way to achieve happiness in a new family.

On May 10th 1844 a baby, Olivia Flora Dean, daughter of Henry & Olivia Flora Dean, was baptised at Christ Church, St Marylebone. The record shows that the baby had been born on February 9th 1843. Then, in June 1844, Henry, son of Olivia Flora & Henry Dean is baptised at St Peter’s, Pimlico. In both entries, Henry Dean is described as a “Gentleman” – a precise designation which would have implied social, and most likely economic, status rather than just being a polite term for a man.

How do I know that this Olivia Flora Dean is the same person as Olivia Flora Dundas nee Burslem? This is where Olivia’s rather unusual birth place of Java is helpful.

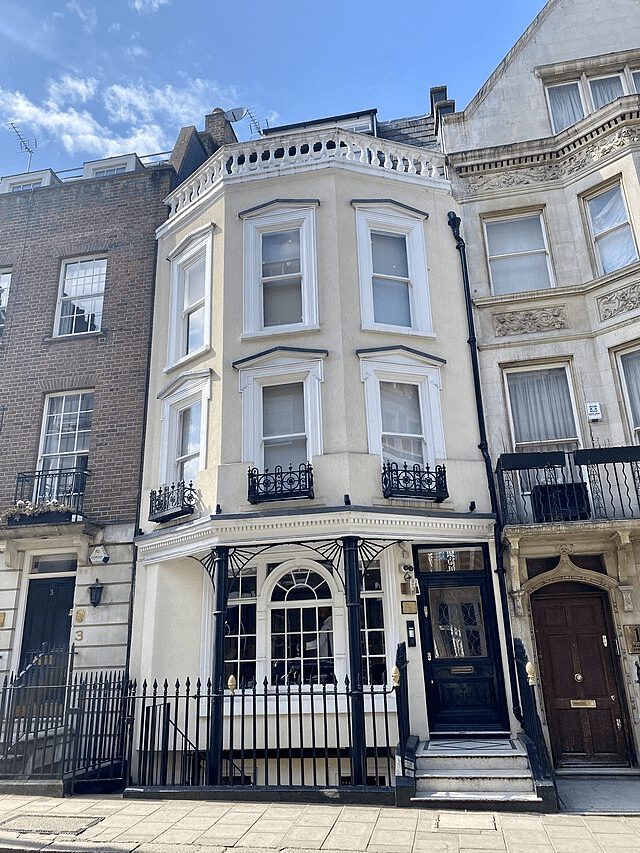

Although I have not been able to find Olivia Flora on the 1851 census, the 1861 census has a Flora Dean, aged 43 and born in Java. She is head of the household at 2, Charles Street, Westminster and lives alone. Her “Rank, profession or occupation” is described as “Householder Independent”. Of former partner Henry I can find nothing, neither is there any trace of son Henry. However, it is very likely that the daughter baptised in 1844 is now identified as Flora O. Dean, eighteen years old and at a boarding school in Brighton.

By 1871, Olivia is still living at 2, Charles Street, but by now her daughter, styled Flora Olivia, presumably to avoid confusion with her mother, is living with her. Son Henry is living there as well, and at 27 he is described as “Retired from army.”

Both Olivia and her daughter Flora are described as “annuitant” which suggests that they are being supported financially, somehow. Perhaps the absent Henry senior – if he is still alive – is supporting his partner and their child, or perhaps Olivia is being supported by other members of the Burslem family – we will never know. There has to be the possibility that both Flora and Olivia are in receipt of support from the Dundas family if not from James himself.

By 1881 Olivia Flora and her daughter are still living at 2, Charles Street, although Olivia is now described as “Widow annuitant”. But whose widow is Olivia?

James Dundas, still living in the lonely canal side vicarage in Kintbury, died in 1872 meaning that Olivia was now legally his widow, even though she had not identified or lived as his wife for so long.

Olivia Flora died in June 1881. It is the entry in the records of Brompton cemetery which confirms for me that the Oliva Flora Dean I have been following through online records is indeed the wife of Rev James Whitley Deans Dundas: the burial register records the deceased as Olivia Flora Dundas of 2, Charles Street – the address at which Olivia Flora Dean had been living for the past twenty years.

The story of Rev James Whitley Deans Dundas and the woman born Olivia Flora Burslem raises questions it is impossible to answer. What became of the child born in Bath before its parents were married? How was James able to secure the living in Ramsbury in 1839 and Kintbury in 1840 despite his somewhat notorious recent past? Or was it that no one in authority – presumably including the Bishops of Salisbury and Oxford in whose dioceses he had ministered – really bothered about it that much?

People will gossip, of course, and Kintbury is not a million miles form East Woodhay, even in a slower age of horse transport. Surely the story of a reluctant groom and a shotgun wedding would be too delicious not to pass on, from village to village? Particularly when the groom is a man of the cloth??

But whatever stories were passed on about the young priest in the 1830s, by the time of his death from heart disease in 1872, James Whitley Deans Dundas was fondly remembered. The Reading Observer spoke of his, “unceasing acts of charity and kindness” and the Newbury Weekly News said he was, “indefatigable in promoting the welfare of his parishioners”. In his time as vicar of St Mary’s, Rev Dundas had overseen a “restoration” of the church, the building of Christchurch at Kintbury Crossways and the building of a new school in the village.

Did anyone in Kintbury know of the estranged wife living in a fashionable part of London? I very much suspect that they did and there may have been raised eye brows and the occasional tuts when stories of Dundas’s past life were passed on. However, to most Kintbury villagers, the life style of the Dundas family must have been so far removed from their own that such irregularities were dismissed with a shrug. And if the Rev James Dundas was regarded as a good man, perhaps any wrong doing in his past would be forgiven.

Rev James Dundas was buried in the Dundas family vault, beneath the chancel of St Mary’s church.

© Theresa Lock, 2025