It seems likely that a branch was first established in Kintbury in 1930 although there are no records of meetings being held until 1933.

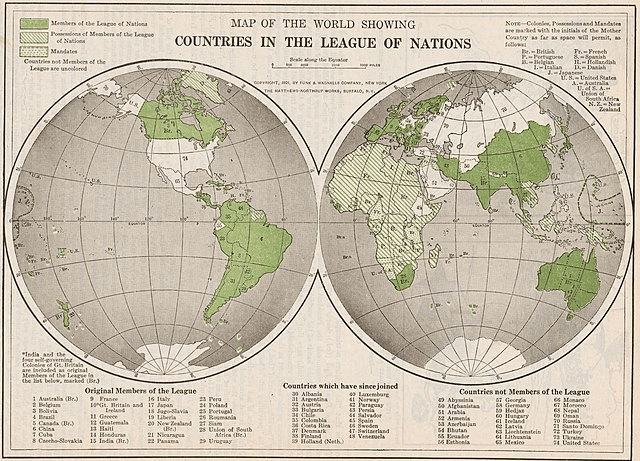

Although the LNU, as an organisation, is now long gone and pretty much forgotten, the minutes reveal a time of awareness of international affairs and a concern for what was happening in the world beyond Kintbury. Meetings in local village halls were addressed by influential and well-informed speakers, reflecting, in its early years, a sense of optimism throughout the LNU. What had happened between 1914 and 1918 must not be allowed to happen again. However, as the international situation deteriorated and the League of Nations seemed increasingly powerless, disillusionment set in, as these minutes reflect.

1933

According to the minutes of the March AGM, held in the Methodist schoolroom, the previous year had seen eight committee meetings and two public meetings, one in Inkpen and one in Kintbury. Membership numbered 86 and included the President, Mr H.D.Watson and Rev’d C.R.G. Hughes who was Hon.Sec. and Hon Treasurer. The committee comprised Messers Lawrence, Rolfe, Pinnock, Browne, Bridgeman and Giles. A very male dominated committee.

The March meeting, a public one, was very well attended. Four members of the Reading Youth Group addressed the meeting on their visit to Geneva and the Kintbury Choral Society sang a chorus. A lively discussion followed.

Committee meetings were held at the Vicarage and between May, and August 1933, five open air meetings had taken place on the Kintbury street corner. In October 1933, Mr. Hughes offered his resignation because of his impending departure from the village.

Education was important to the LNU and across the country schools were encouraged to take up corporate membership as were cooperatives and also churches.

In November, 1933, a Mr. Archer came to Kintbury from the Federal Council to address members and local schoolchildren. He apparently gave ‘every satisfaction’ and proved himself capable of keeping the children to whom he lectured at a ‘high pitch of interest’.

1934

A year later in November, 1934, committee meetings were resumed in the vicarage as the new vicar, Rev’d Guthrie Alison, became a member of the League. It was agreed during this year to canvass the village for the Peace Ballot, which was being organized across the country. Nationally, over 11 million people voted in favour of the aims of the LNU. In Kintbury, 540 voting papers were collected, but the time taken to organise the ballot locally prevented canvassing for new members and there was a slight drop in membership. However, Mr. Alison recruited at least one new member in November, Mrs. Goodheart of Inkpen.

1935

On a wet summer evening of 19th July, 1935, a very enjoyable and successful meeting and whist drive took place at ‘Windrush’, home of Mr. H. D. Watson. Sixty members attended and partook of pleasant refreshments as well as listening to an attractive and illuminating speech by Mr. Alec Wilson on the work of the League.

LNU Head Quarters suggested an effort be made to increase membership by arranging a campaign. However, the Kintbury contingent felt that this had better be left until after the General Election in November and until after the Italo-Abyssinian war had concluded. Mussolini, the Italian leader, had invaded Ethiopia (Abyssinia) with the intention of expanding Italian influence across East Africa. Such aggression ran counter to the pacifist-mindset of many in the LNU.

In October, 1935, Mr. Alison read aloud a pamphlet on ‘Five Minutes of Your Time’ by A. A. Milne, the popular author who was, at that time, a pacifist. This was sent by H.Q. and deemed very suitable for propaganda. (Used here and at that time, the word did not imply political or ideological bias as it has since come to mean. It implied more of a dissemination of information.)

All branches were asked to find the views of their parliamentary candidates on the vital international issues of the moment. This, Mr. Watson had done for the Kintbury Branch and he drew attention to the answer of local M.P. General Clifton Browne in the Newbury Weekly News.

In November, Mr. Alison, now President, talked of his recent visit to Geneva and his inspection of the League of Nations’ new building. There was a suggestion of acting a play for propaganda purposes but, as the last play had not been a success it was decided to postpone the suggestion. Arrangements were made however, for a public meeting to be held in December, in the Coronation Hall, Vice Admiral S. R. Drury Lowe to speak. The vicar was successful in gaining the consent of Barton Court’s Lord Burnham to take the chair.The secretary was asked to communicate with the Heads of the Mothers’ Union, Women’s Institute and Christchurch School regarding this meeting and the vicar was to give notice in church and see the Head of St. Mary’s School. It seems every effort was being made to ensure this meeting was well attended.

1936

Another public meeting was held in Inkpen on Wednesday, 29th January, 1936. An omnibus ran from Kintbury to Inkpen free of charge and a good many members availed themselves of this facility. Fifty or more people were present to hear the most fluent explanatory and interesting speech by Mr. Anthony Mouravieff. Mouravieff, a Parliamentary Private Secretary to an MP, and a prominent member of the League, was a popular speaker on international affairs and addressed many branch meetings across the country at this time. Inkpen must have been lucky to secure his appointment to address their meeting. Discussion followed with several short speeches made with animation and new members enrolled.

At the February AGM, Mr. Pinnock mentioned that Mr. Liggins secretary of the Thatcham Branch would be willing to bring a cinematograph with a League of Nations film to Kintbury!

Meanwhile, the crisis surrounding Abyssinia had not been resolved. The League of Nations had banned weapons sales although these actions were generally ignored by Mussolini. The British government wanted to keep Mussolini on side as an ally against Hitler and were reluctant to enforce sanctions. Together with France, Britain began secret negotiations with Italy without involving the Ethiopian leader, Heili Selassie.

Britain had adopted a position of neutrality and non-intervention with regards to the Spanish Civil War which began in 1936. This way, it was reasoned, made it less likely that the conflict would escalate. However, many young idealistic British men and women travelled to Spain to fight against the rise of fascism. Despite many countries having signed the League of Nations’ Non Intervention agreement, this was ignored by many; Italy and Germany provided military support to Spain’s military general Franco who was aiming to establish a fascist dictatorship. For many, events in Spain served to illustrate how ineffectual the League of Nations actually was at preventing or resolving conflict.

In Kintbury, a resolution was proposed and sent to H.Q. that:

‘the Branch expresses its concern about the present position of the League in relation to the action taken by this country alone in the Mediterranean without a mandate from the League and would be interested to know if H.Q. of the League considers that such concern is justified’.

In June the League was in sad financial straights. Indeed. Mr.Jowett, organising secretary for Bucks, Berks and Oxon, was told that his salary must cease owing to the need for economy. However, he agreed to carry on for a while without salary. Mrs. Goodheart meanwhile, resigned from the committee and the Union. While still believing in the ideal, she could not approve of the Union or belong to it. The worsening political situation must have made many people reconsider where they stood on issues such as pacifism and appeasement.

Another open air meeting was proposed for late July. Unfortunately, July, 1936 was extremely wet and as rainy day succeeded rainy day, an open air meeting became impossible and instead an open meeting was held in the Methodist schoolroom.

Mrs. Corbett-Fisher made a strong and extremely interesting speech and the popular amateur dramatic group, the Reading Pax Players performed “Gas Masque”. This was fresh, well-acted and caused much amusement – it was sadly disappointing that so few people came.

In October it was announced that nationally, 3,000 more members had joined than at the same time last year. The Chairman, who had attended a meeting in Scarborough, went on to report that

‘The League is always most useful in some matters if apparently useless to stop a war. The constitution was not elastic, not workable with regard to some affairs – but might be altered.’

When the League’s debts became known people hastened to its support and £10,000 raised to pay the debt. There was still enthusiasm and resignations were not taking place in large numbers. Discussion took place on the League’s actions and inactions. Mr. Padel wished to form a protest from Kintbury with regard to the League’s inaction in relation to Abyssinian and the Spanish troubles. The League was not doing its duty, he believed. Mr. Giles opposed intervention in Spain but joined in warm criticism!

The vicar resigned as a committee member in November. Whist Drives were suggested as a fund raiser but it was thought that these were overdone at the moment. There followed a discussion concerning the International Peace Campaign – a movement started in 1935 as a response to Italy’s invasion of Abyssinia. Mr. Giles hoped that the League of Nations would try to prevent war, not wait and only try to stop it when it had already begun.

On December, 7th, 1936, there was a public meeting in the Methodist Schoolroom. The Chair was taken by Lord Faringdon and the Speaker was once again Vice Admiral S. R. Drury-Lowe, who had achieved splendid work for The League. The Admiral spoke of the difficulties and weakness of the League at times but stressed its great possibilities and unique position. He spoke of its inability to stop the last war of aggression, but its immense good in the cause of workers in all parts of the world. It did much good for children and had opposed the opium and so-called white slave traffic, doing work no other organization could do. There was no other organisation to do the work. It must be helped and strengthened to allow it to rise to greater power and influence.

It was an extremely cold evening with a searching wind, the attendance at the meeting was very poor. The Vice Admiral had a whimsical story and a light touch to occasionally relieve his earnest speech, but no new members were made and no new faces seen.

1937

By 1937, the financial situation of the local branch seems to have been less than robust as at the March meeting Mr. Pinnock was asked to find out from the Methodist Trustees, Mr. Phillips and Mr. Mackrill, if the schoolroom could be hired for less than the usual five shillings.

The following month, at the A.G.M. the President, H. D. Watson Esq. gave the little meeting an informal, delightful talk as they sat around a fire. He spoke of his recent visit to Geneva where the League was housed in a magnificent building. However, he reported an atmosphere of depression as regards the peace work of the League particularly amongst the Italian delegates.

In the International Labour Section there was a keen and enthusiastic spirit, as if the good work done was heartening. He spoke of the wonderfully good work done in the ‘Save The Children Branch’ its great activity and hopefulness. The League was doing magnificent work for the so-called white slave traffic, drug smuggling and slavery.

It was decided that all accounts must be audited as was the case in all other Kintbury Societies.

The Vicar consented to be Vice-President again. As H.Q. was in great need of money Kintbury forwarded ten shillings in November 1937.

1938

The public meeting on January, 17th, 1938, was a great success. Miss. Chu Chan Koo (Miss. Wellington Koo), daughter of China’s representative at Geneva, made a moving speech on the history of China and its present sad state which was particularly well received. This was followed by a short pageant play entitled ‘Friendships Chain’. The parts were taken by 23 Kintbury ladies and girls and watched by an audience of over 200 people. A collection for medical relief for Chinese sufferers raised £3-17s-0d.

It was announced that Mr. Lloyd resigned as President of the Berkshire Federal Council. He still adhered to the League of Nations but not to its instrument, the League of Nations Union. Lord Neston of Agra agreed to take his place.

At the March meeting of 1938, the committee spoke with great regret of the death of Mr. Rolfe, ‘an important member of the committee’. The committee also lost two other members, Miss Joan Ewins resigned and Mr. Gordon Abraham moved to Surrey.

Mr. Watson continued as President. He had just visited Geneva again and reported on the international situation which was not optimistic. In May, it was explained, Italy will require Abyssinia to be acknowledged as part of the Italian Empire. All nations, with the possible exception of Russia, will have to do this. It would be necessary for Great Britain to recognise Italy’s conquest of Abyssinia in order to keep the peace and be on good terms with Mussolini. In return, Italy was apparently anxious to maintain good relations with Great Britain because of affairs in Austria.

The outlook in Geneva seemed gloomy and the League was anxious. Great Britain still believed in the work of the League but acknowledged that reconstruction of it might be necessary. Although it might not be able to maintain international peace it still had important work to do regarding the sale of dangerous drugs and so-called white slave traffic, and, importantly, continuing to help all refugees and keep up the Save The Children Fund.

Mr. Watson was thanked for his talk and the vicar continued in a ‘happy little speech’, to hint that such an end as peace perhaps justifies the means i.e. the recognition of Abyssinia’s conquest. A lively general discussion followed.

In May, the vicar suggested that a meeting be held soon in Kintbury in which a speaker could explain the current situation in central Europe, particularly with regards to Czechoslovakia and the threat to peace. This was arranged to take place in the Coronation Hall at 7.30pm on Sunday, 19th June.

Mr. Anthony Moore gave an interesting address to an audience of fifty to sixty people. He explaining that the Czechoslovakians are not an upstart nation, but Bohemians, a small nation now since the 14-18 war. Their country was a buffer state with a German minority population likely to cause trouble, he believed, in the near future. It was Hitler’s intention, he explained, to acquire all the smaller nations of Central Europe. The Germans, he believed, had taken against the Jews because they were “international”.

The League of Nations Union has passed a resolution to ask the British Government to support Czechoslovakia and present a bold front to Hitler.

Mr. Moore answered several pertinent questions from the audience, who keenly enjoyed his fluency and grasp of the subject. A vote of thanks was warmly seconded by General Rennie, who said that he appreciated the speech but not the League of Nations Union. The vote was carried with acclamation.

1939

Attendance at the May A.G.M., 1939, was very poor: President, Secretary, Treasurer, four committee members only. At the Public Meeting that followed, Mr. Alec Wilson, M.I.R.A., gave a short, optimistic speech: ‘After the Great War there were widespread results. The League of Nations was formed to help peace and goodwill among nations. After the great slump set in over the world, Germany was very low in money and work. Hitler, whose plans were for all Germans to be one huge family, rose as Dictator or Leader. His book, ‘Mine Kampf’, shows his idea that the Germans are the only people fit to govern Central Europe’.

The lecturer traced events from 1914 up to date, showing how the German threat to Poland arose and that part of South Russia called the Ukraine. Wilson was of the opinion that Britain’s alliance with Russia posed a problem as the British had a dislike for communism and also there was much danger in naval and military commitments in a vast distant territory.

On 30th July, 1939 it was decided that ‘the time had come for the Kintbury and Inkpen Branch to acknowledge that no work was done in connection with the League of Nations’.

The Treasurer, Mr.Pinnock, had left the neighbourhood, the Secretary, Mrs. Norton, said she wished to resign because the League of Nations Union seemed quite dormant here and she had other work to do. The President said that although other branches were closing many were active, especially in the north. He wished some remnants of the branch to be kept – in view of a revival, when their time came again, when peace was near. The vicar agreed to keep the minute book and list the members until peace came and a working secretary was needed.

Ironically, peace was to be a long time coming as war broke out across Europe in September of that year. The League of Nations was officially disbanded in 1946 although its aims and intentions were enshrined in the United Nations, established by charter in 1945. Its work continues to this day.

(c) Penelope Fletcher, 2024