This post is in two parts. In the first part, I consider the village of West Woodhay from a changing historical perspective. For the second part, we are delighted to have a contribution from Harry Henderson of West Woodhay Farms in which he describes the recent changes in agricultural practices which have enabled vitally important regeneration of the land.

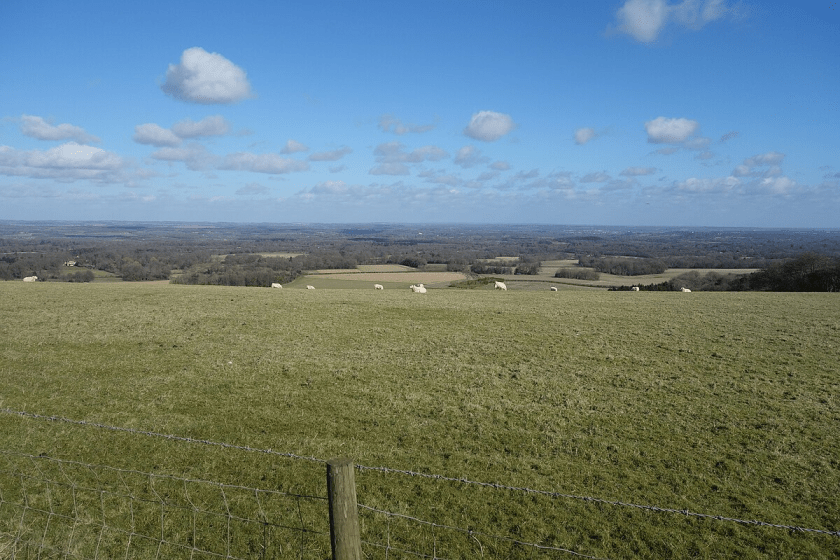

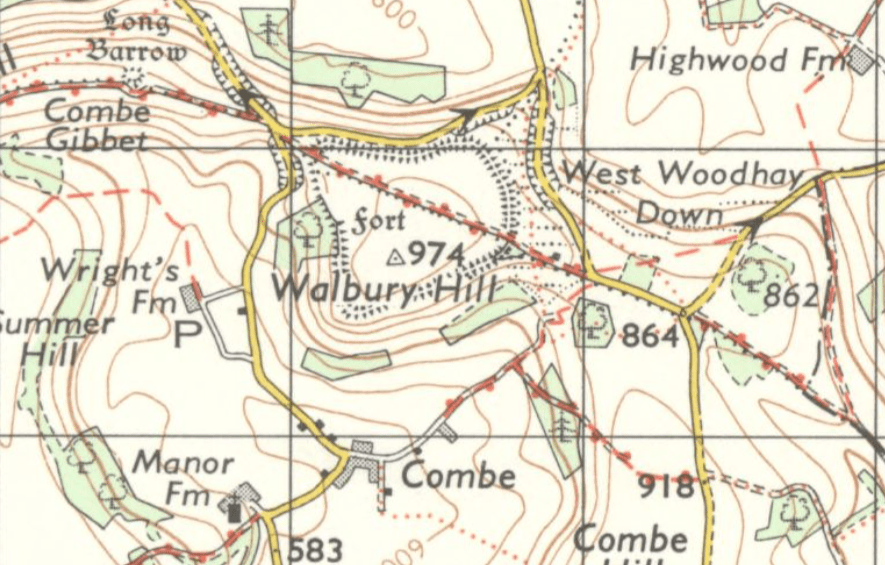

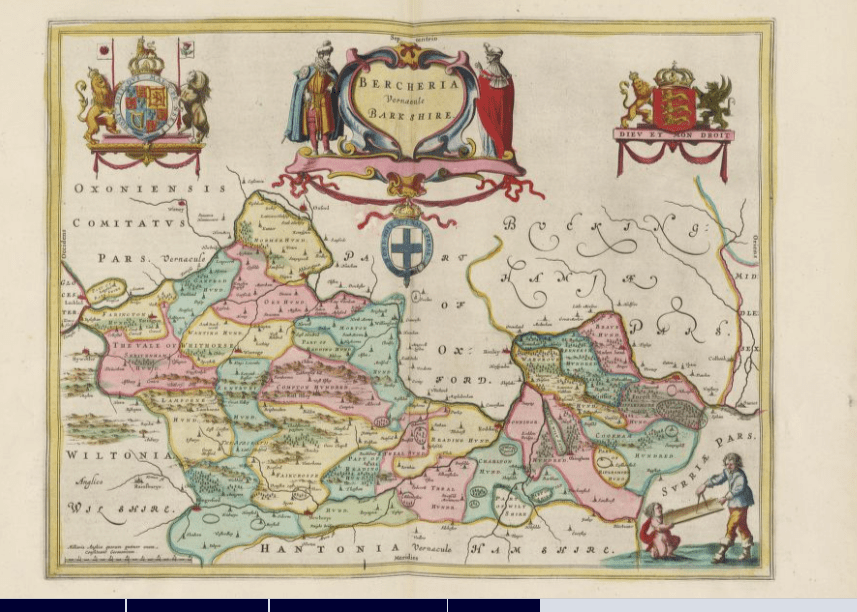

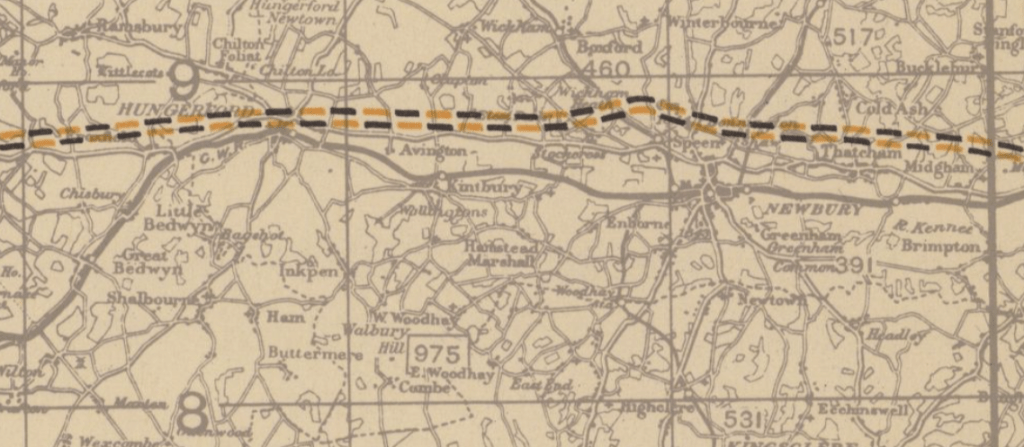

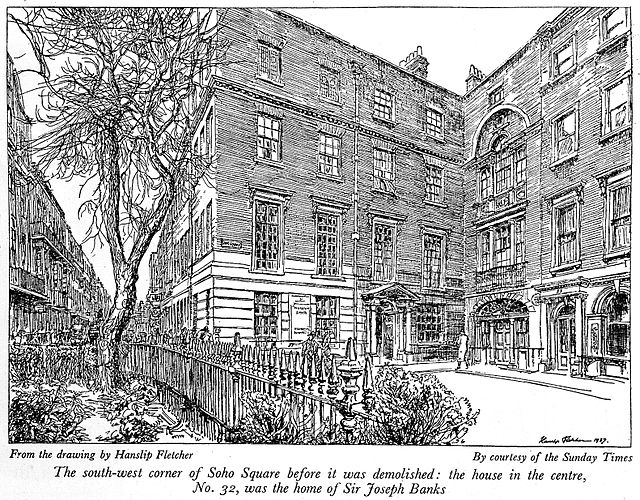

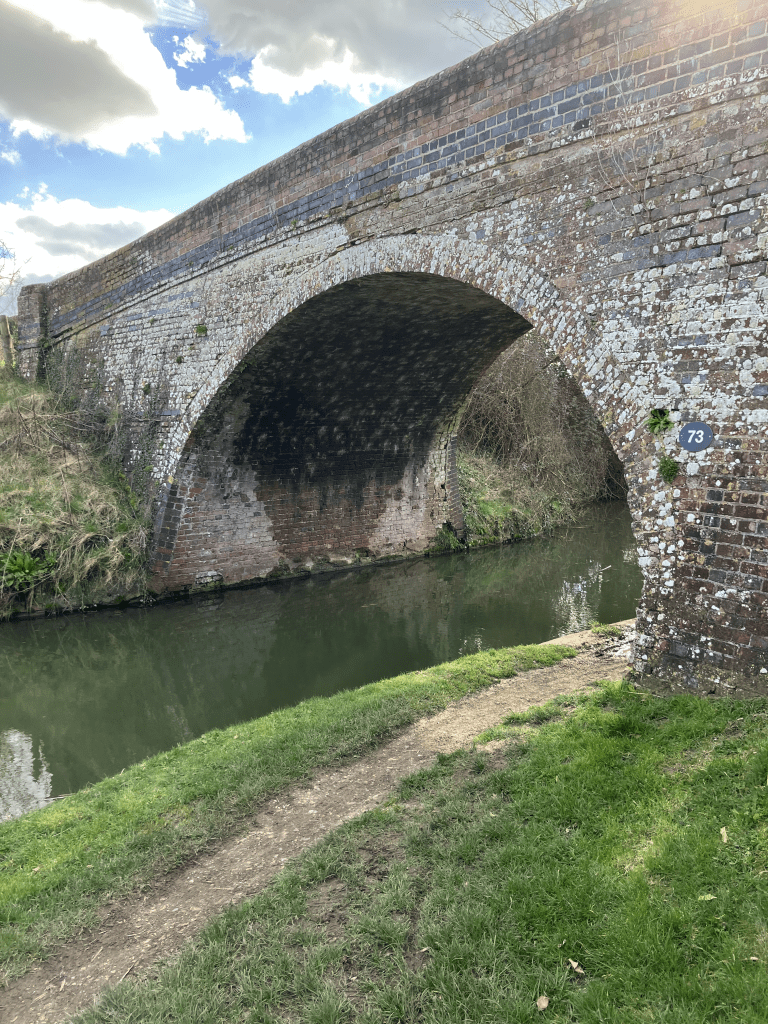

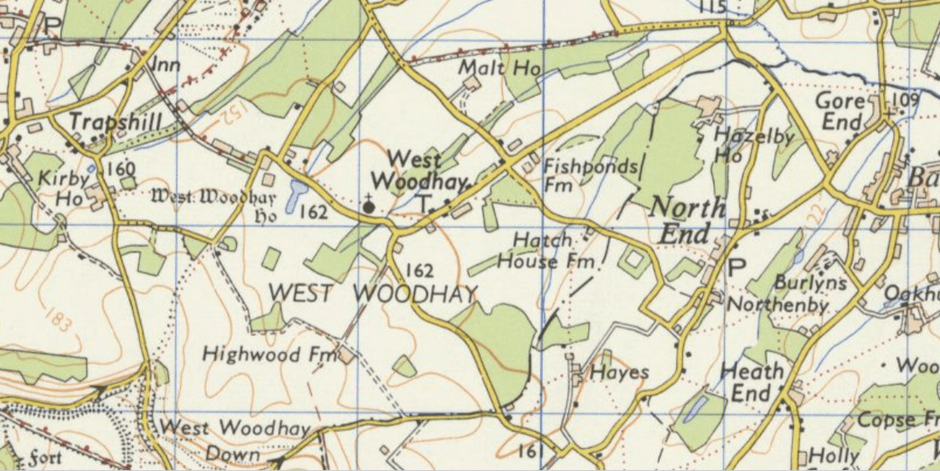

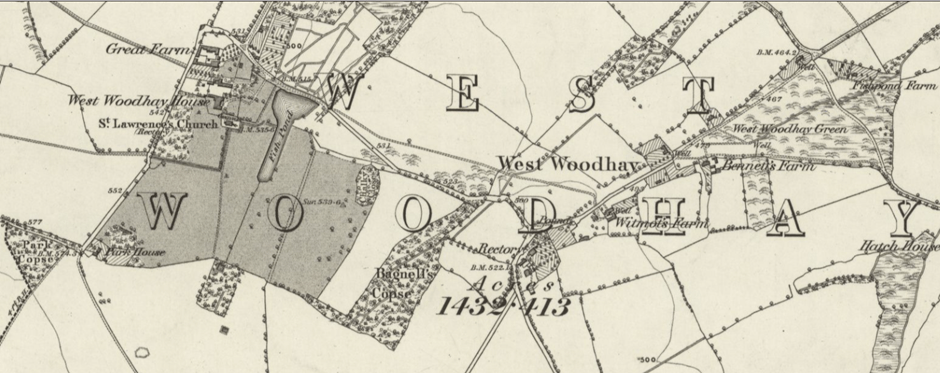

On the road to nowhere in particular, the hamlet of West Woodhay is situated in the extreme south of West Berkshire just below the North Hampshire downs, a little over two miles south of Kintbury as the crow flies.

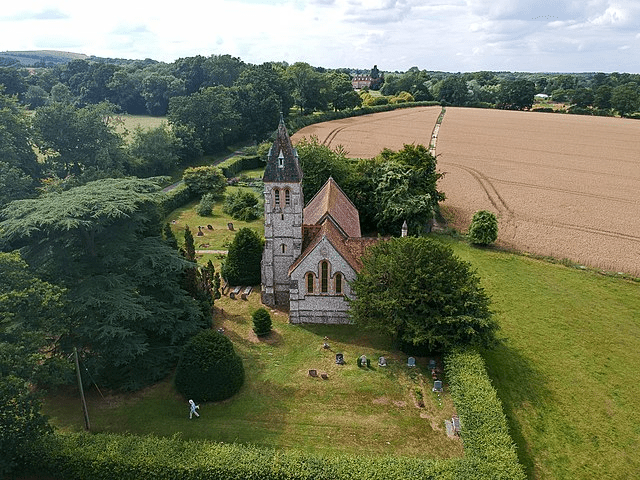

Although a motte is all that remains now of a twelfth century hunting lodge, today the village is probably best known for the elegant grade one listed West Woodhay House and also the grade two listed St Laurence’s church with windows by Morris & Co.

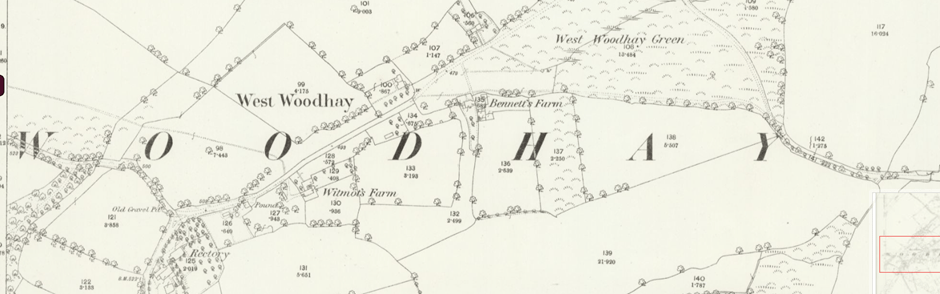

Early censuses show that most of the population were engaged in agriculture during the nineteenth century; early maps of the village suggest there has been little if any development, so, on the whole it might be presumed that very little of any great note has ever happened here. However, the effects of very significant changes in agricultural practices can be traced in the history of this village and the surrounding area.

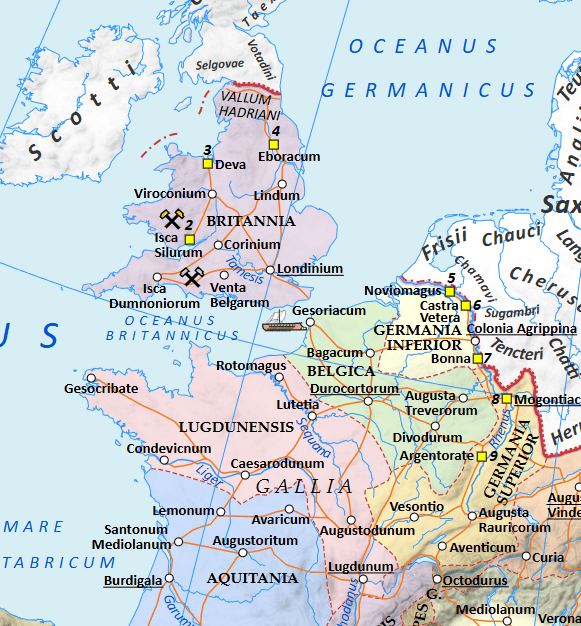

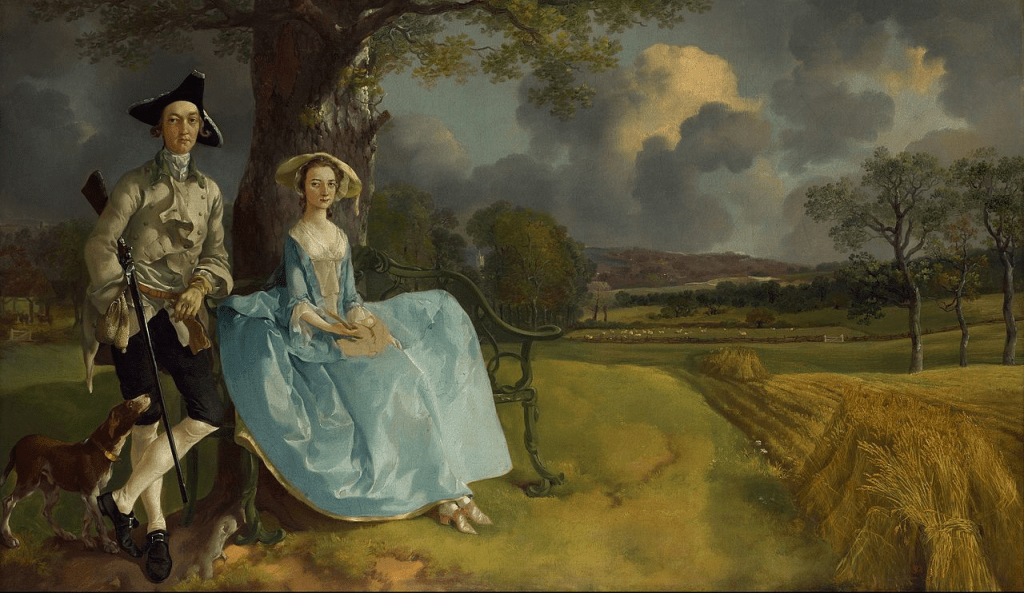

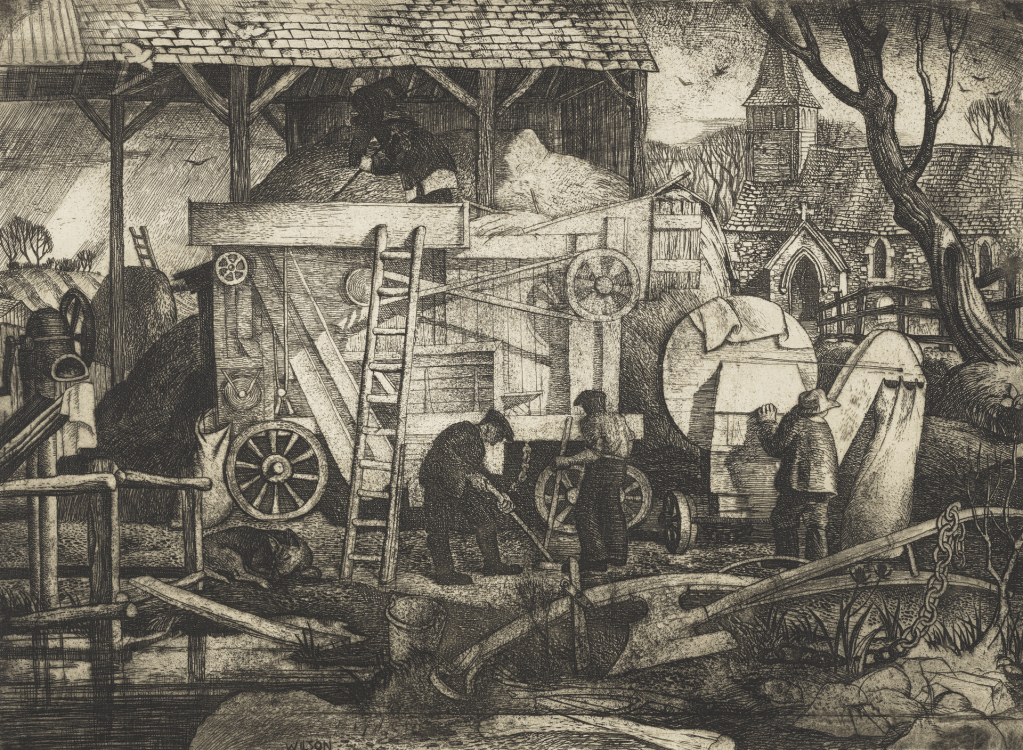

The eighteenth century saw many developments in agriculture, enabling increased food production necessary to feed the growing population. Whilst innovations in agricultural machinery, such as the horse drawn seed drill developed by Jethro Tull of Prosperous Farm, near Hungerford, made the cultivation of larger fields much easier, this had a downside for thousands of rural labourers.

Since medieval times, many rural families had cultivated strips or patches of land, often dotted around their parishes, relying upon what they could grow to feed their families. However such a system was useless for food production on a large scale. The 1773 Inclosure Act enabled the Lords of the Manor or other land owners to enclose the diverse patches and strips of land, creating large fields each devoted to one particular crop and of the size that could be cultivated using new machinery. Whilst this might have been good news for the markets, it was devastating for many who lost their ability to grow their own food.

The effects of the 1773 Act were not felt straight away although it was eventually to change the face of the English countryside.

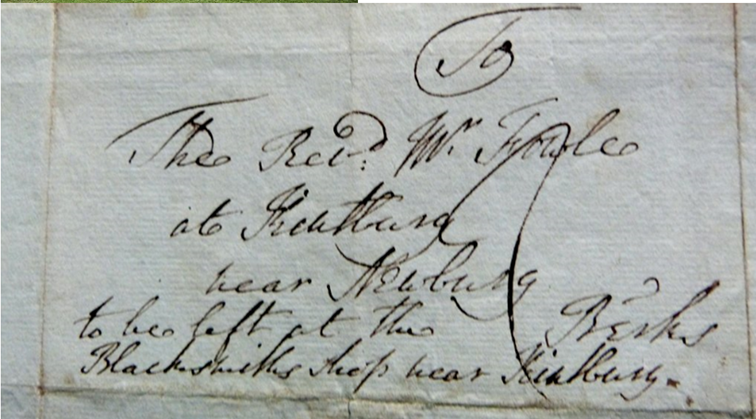

The Hampshire Chronicle of July 1816 reported that an Act of Parliament had been passed for the inclosure (sic) of Woodhay Common. However, “the labouring poor in that neighbourhood have lately shewn strong symptoms of their disapprobation and at length proceeded so far as to collect in considerable numbers with the avowed intention of preventing the farmers ( to whom it had been allotted ) from breaking it up.”

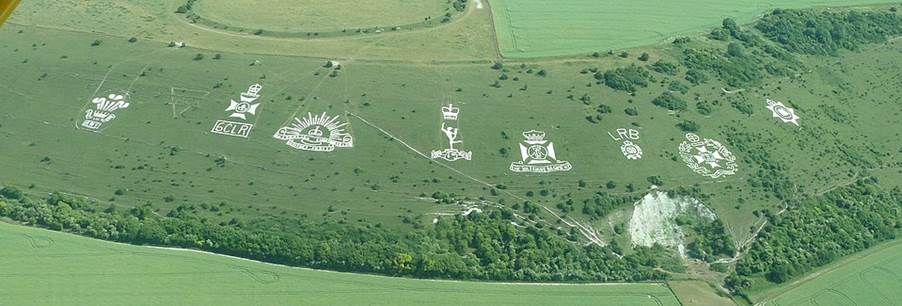

Fearful of trouble, the authorities called out military back-up which arrived in the form of the “Donnington and Newbury Troop under the command of Capt. Bacon” and also “Oxford blues ( who had been sent from Maidenhead )”

It is hard to believe that anyone would have felt it necessary to employ the military to prevent any sort of a riot in such a quiet and peaceful corner of the county. It is hard to imagine troops, not just from nearby Newbury but also from Maidenhead, well over a day’s ride away, descending on the village. Insurrection is not something you would associate with West Woodhay.

However, due to the “spirited exertions of constables” the military were not required although several of those involved in the protest were bound over to appear at the Quarter Sessions.

Enclosures were not the only things to make life increasingly difficult for the rural poor. Harsh game laws meant the penalty for catching rabbits for the pot could be transportation and poor harvests in the 1820s resulted in increased prices, particularly for bread.

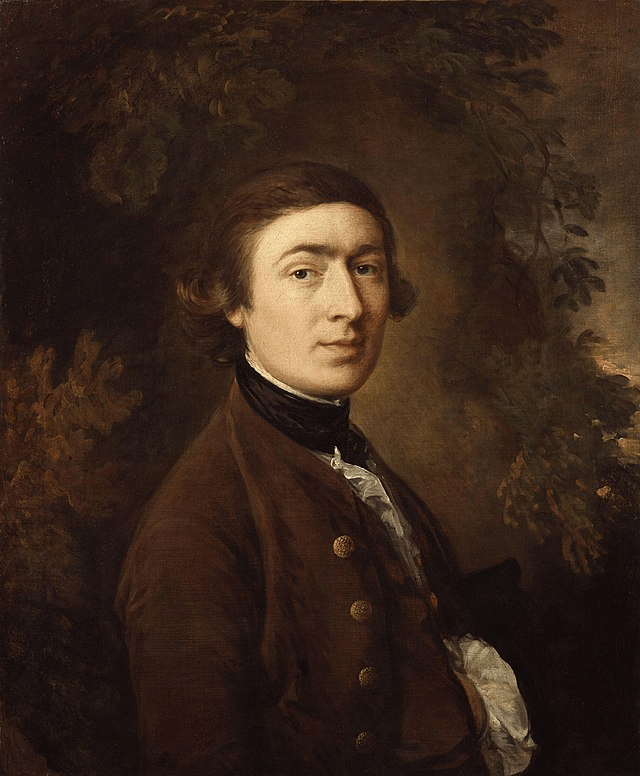

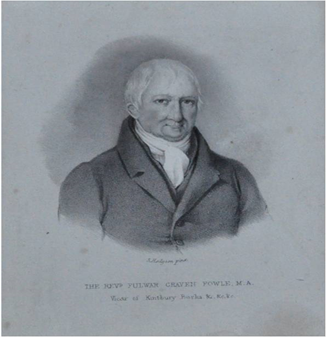

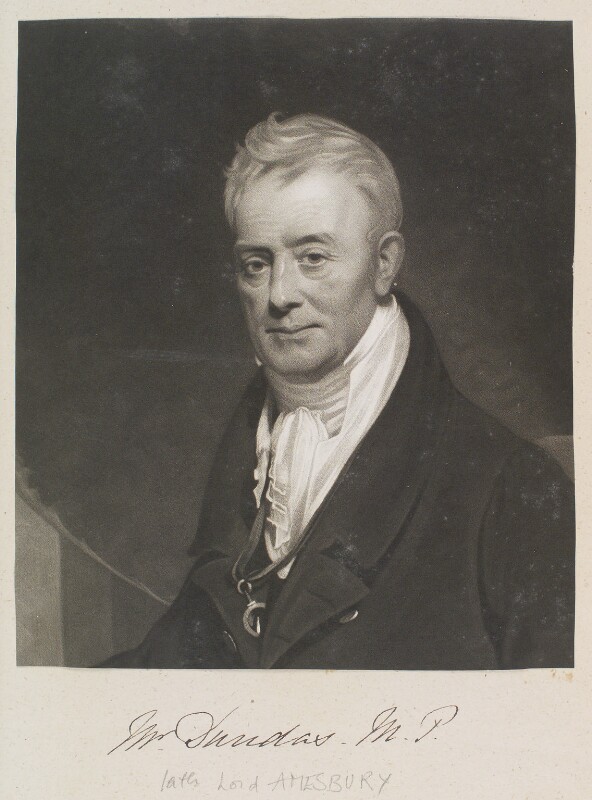

William Cobbett was a writer and campaigner born in 1763 to a Hampshire farming family. Critical of the way new laws impacted upon the rural population, in 1821 Cobbett set out on a series of “Rural Rides” to observe for himself the situation throughout the midlands and south of England. Amongst other things, Cobbett was critical of the amount of money the country was spending on defence rather than on improved conditions for the rural poor. One of those of whom he was particularly critical was Berkshire M.P. and Kintbury resident, Charles Dundas. A prominent and influential figure, Dundas would have been well known across local towns and villages.

Although it is not always easy to work out Cobbett’s exact route through the countryside, it is clear from reading his work that he travelled across North Wiltshire and into Berkshire, stopping at Newbury on October 17th.

Whilst at a public dinner in Newbury, Cobbett took the opportunity to call out Dundas’s false accusation that he, Cobbett, was complicit in a plot to assassinate the Prime Minister and members of the cabinet. Known as the Cato Street conspiracy, those involved were eventually either executed or transported. For Dundas to accuse Cobbett of complicity was a particularly serious slur and something which reflects how polarised political views were at this time.

Later, Cobbett observed that “a good part” of the wheat offered for sale at Newbury market was wholly unfit for bread flour. Considering the importance of bread in the diet of poorer people, this must have led to severe consequences locally.

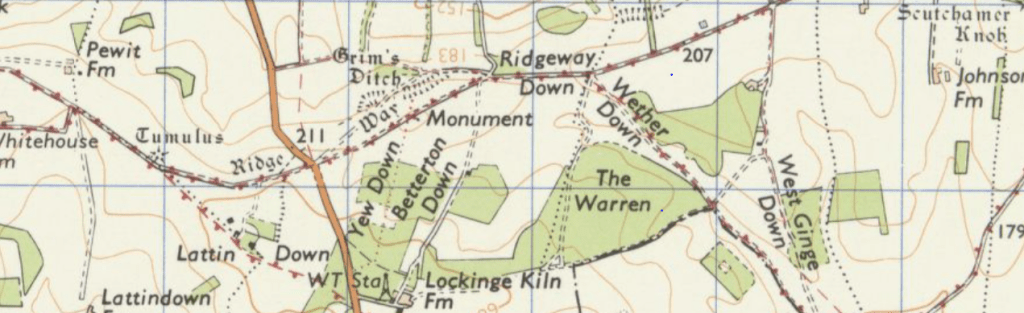

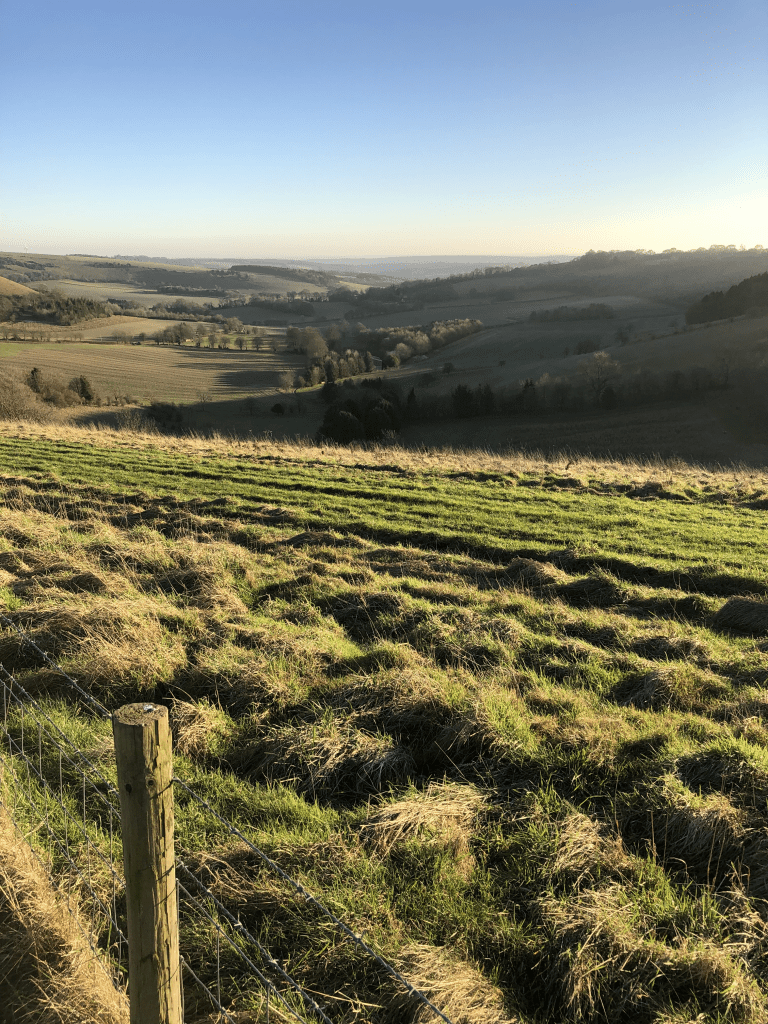

Not everything Cobbett observed as he rode through the downland was negative, however. At one point as he rode across the downs, he observed, “immense flocks of sheep which were now ( at ten o’clock ) just going from their several folds, to the downs for the day..”

The “immense flocks” aside, there was, as Cobbett noted, little to impress in the daily lives of the agricultural workers. Enclosures, the rising cost of bread and harsh laws which mitigated particularly against rural people, and changes in agricultural practices such as the introduction of mechanisation made life for the agricultural worker extremely difficult. The bad harvest of 1830 was the tipping point, leading to what became known as the “swing riots” which broke out in December of that year.

Although most of the protests in this part of West Berkshire were centred on and around Kintbury, West Woodhay did not escape the disorder. Here, Cornelius Bennett and Henry Honey were charged with robbery although both were subsequently acquitted. However, shock waves must have rippled across this part of Berkshire when it was reported that others of the rioters had been charged at Reading Assizes with several transported to Australia and one executed for his involvement.

In the following years, however, the agricultural industry in England generally was thriving. But this was not to last and by the 1870s it was in depression. By 1893 an anonymous contributor wrote to the Newbury Weekly News:

“There are thousands of acres not tenanted at all, and scores of landlords only too anxious to let on almost any terms.”

He continues:

“The real cause of agricultural depression is very easy to find, but very difficult to remedy. It is because the enormous development of steam navigation has brought the millions and millions of foreign acres into practical proximity to our shores and accompanied by a full market has made England a central emporium of a huge percentage of the surplus produce of the world.”

Throughout England, the numbers of people engaged in agriculture, particularly as labourers, declined as many sought better paid factory work in towns and cities. In West Woodhay, the 1851 census records William Taylor of West Woodhay farm as employing 15 labourers. By 1861 the farm has been taken by an in-comer from Buckinghamshire, Job Wooster, who employs 9 labourers. By the 1881 census, there are just 16 agricultural labourers in the whole of the village.

Throughout the early years of the 20th century, many young people from rural communities emigrated to the colonies such as Canada or Australia to try their hand at agricultural work far from home. Whilst I have not been able to discover how many pioneering young men or woman left the villages of West Berkshire in this way, it has to be likely that some, at least, would have done so.

The twentieth century witnessed two world wars during which thousands of agricultural workers from all over the country enlisted in the armed forces. To make up the short fall in manpower, thousands of young women joined the Women’s Land Army and were posted to rural areas throughout the UK. In July of 1918 the Reading Standard featured on its front page photographs of some of these women at work on Berkshire farms under the bold sub-headings:

THEY MILK THE COWS

AND FEED THE PIGS

AND TRUSS THE LOADS OF HAY

most probably to the cynical and wry amusement of those rural woman who had been undertaking farm work for decades.

The 1939 Register lists 24 people engaged in agriculture in West Woodhay although it is difficult to draw an exact comparison with numbers of agricultural workers at the time of the nineteenth century censuses in part due to changing definitions of occupation. However it is true to say that the village had remained a predominantly agricultural community.

It is now over 200 years since West Woodhay Common was enclosed and 195 years since the Swing Riots. Although the associated violence is now very much in the past, the farm lands of West Woodhay still reflect the changing agricultural practices and the need for farming to respond to changing times.

For the second part of this post we are grateful to Harry Henderson whose family owns and runs West Woodhay Farms, an estate on the Berkshire/Hampshire border.

(C) Theresa Lock 2025

Farming for the Future: Soil, Sustainability, and Success at West Woodhay

Harry Henderson

The estate spans 830 hectares of challenging land with fragile soils. Since 2008, a regenerative agricultural policy has been in place, with a focus on prioritizing soil health. The estate now follows a crop rotation system that includes herbal grass leys, flower meadows, wild bird feed areas, and very low-input cereals.

Agricultural chemicals and fertilizers have been replaced with more sustainable cultural methods. As a result, there has been a significant increase in soil biology, leading to enhanced organic matter levels and improved carbon capture.

The shift in farming practices—driven by soil health—has led to remarkable nature recovery. The planting of herbal leys and wildflower plots has created a thriving environment for insect life. Since adopting a no-insecticide policy in 2014, West Woodhay has seen a resurgence of beneficial insects such as spiders, beetles, and parasitic wasps. This has enabled the successful establishment of flea beetle-sensitive crops like stubble turnips.

The rise in insect populations has also benefited birdlife, which is supported further through the planting of wild bird plots for the leaner months. All this recovery work has been monitored and independently audited over many years, and the data clearly shows a strong link between soil health and biodiversity.

In-depth soil analyses have shown that, given time and the absence of soil disturbance, soil indices can begin to rebalance naturally, making primary nutrients more available to crops. This reinforces the estate’s approach of minimal intervention and maximum biological support.

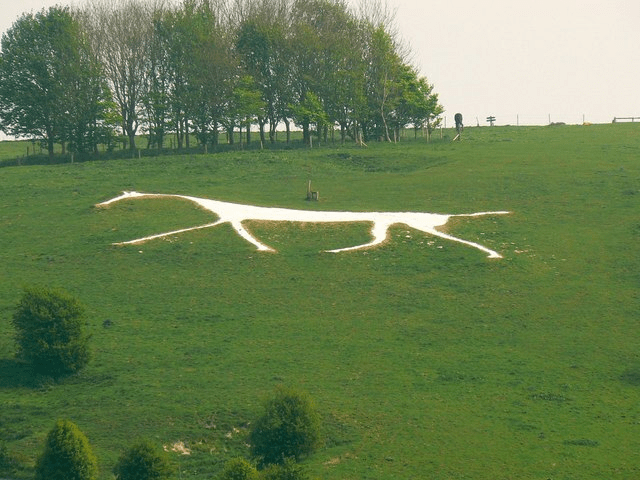

A large sheep flock has been used to manage the land and maintain productivity. The breed of choice is the Welsh Cheviot, native to the Brecon Beacons. With West Woodhay’s highest point reaching 900 feet, this hardy breed is ideally suited to the challenging upland climate. Their thick, dense fleece protects them from January’s easterly winds and rain.

Lambing begins in late March, with all ewes lambing outdoors in a natural environment, giving mothers plenty of space and time to bond with their lambs. During the summer months, the flock grazes on the herbal leys, enriching the soil’s biodiversity. After weaning in early autumn, they are moved to higher ground to help manage the fragile downland ecosystem.

The estate’s latest and most exciting initiative is the production of cereal crops for human consumption, grown with little or no artificial fertilizers or pesticides. These crops are established using zero-tillage methods. By using legumes to naturally supply nutrients for fast-growing spring cereals, West Woodhay has successfully tapped into new opportunities through Wildfarmed contracts.

Importantly, the farming enterprise has remained consistently profitable. Without profit, nature recovery would be difficult to sustain. Savings on fertilizers, agrochemicals, fuel, finance, and labour have helped support this transition. The increase in soil organic matter has broadened the estate’s cropping options, helping to future-proof the farm for the next generation.

(C) Harry Henderson