Now, as a mere woman, I would not have been able to attend these meetings, however the minute books were passed to me as a possible source of parish history.

The minutes make interesting reading – on the one hand they reflect an echo of earlier time, for example the home- grown entertainments at the Christmas Party could belong to the previous century, whereas the discussion of the Wolfenden Report into Homosexuality reflects a consideration of changing attitudes more associated with the 1960s. The minutes record several comments which reflect some opinions and values of the time and which would cause raised eye brows if expressed today.

I’ll begin by eavesdropping on the November meeting 1956. All, as the minutes say, were ‘seated in comfort, thanks to the vicar’s good offices’.

The talk was, as you might expect from a Christian fellowship, an exploration of the Bible. The speaker was Kintbury’s Mr. Sidney Inns (well- remembered by many of us). Sid, it says, probed with an historian’s knowledge into the early writings of the bible. So enjoyable and instructive was the talk that Sid had to promise a further contribution.

This meeting ended with plans being made for the Christmas Party, to which members could invite six people each, and a “Practical Day”, during which members would decorate the Parish Room. Finally the vicar drew attention to ‘Operation Firm Touch, a means of influencing adolescents back to church’ – so much for those who say that only this generation has deserted the pews.

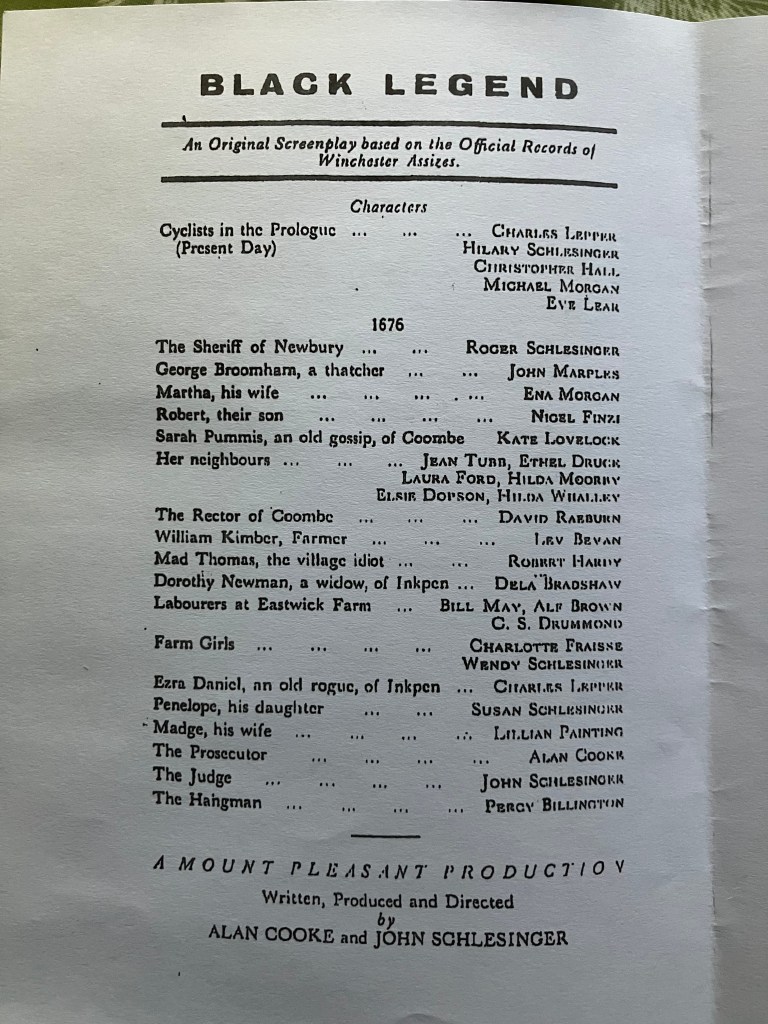

The party was held in the Coronation Hall on 5th January and seems to have been quite popular as approximately ninety people attended. Entertainment was provided by local people and included Mrs. Bailey and Mrs. Aldridge performing a sketch called ‘Over The Garden Wall’, The Kintbury Handbell Ringers, Gordon Perris singing a selection of popular songs, accordion players Geoff White and Miss Pat Reeves, and four ladies who, apparently, gave a hysterically funny performance of the play, ‘Mr. Macgregor comes to Tea’. Finally the Men’s Fellowship performed the ‘Berkshire Widdicombe Fair’. This last item was so popular that it was asked for over and again at different gatherings.

However, it is the next meeting that fascinates me most. The Vicar said that he really found it rather difficult to find a suitable bible passage for the topic under discussion. This does not surprise me for the topic was ‘Flying Saucer – Fact or Fiction’

A Mr. A.E. Jones proceeded to convince everyone present that flying saucers were not purely figments of the imagination but really existed. He explained that they had been observed in 1619 and now in 1956 a schoolmaster on the Yorkshire Moors had been confronted by a visitor from Mars and had experienced a strange feeling of peace almost as if the visitor was a deity. Mr. Jones produced other testimonies ranging from Norway to the USA and added the information that the saucers were reckoned to travel at 9000 miles an hour.

Not surprisingly after this stirring stuff the group returned to a safer subject, ‘The Drift From The Churches’. The minutes say that this was the first meeting in the redecorated Parish Room and maybe the brightness of the room demanded that the meeting be bright as it undoubtedly was. But was it safer than flying saucers – it was certainly a healthy discussion.

‘The Church in its capacity as the established church had backed the wrong horse probably due to tradition and the bowing to the demands of the wealthy section of the community, said Mr. Parry, the leader of the discussion.

This was most likely a controversial opinion to hold in the 1950s. Mr. Parry believed that 40 years ago a large number of poor people attended church regularly, thereby to gain spiritual salvation. Now one could only imagine that the lack of poverty had increased physical greatness with a consequent falling off in spiritual discipline.

Mr Parry was of the opinion that Sunday was now largely a family day, whereby most of the family could be together. No doubt the motor car and coach trip also accounted for absent seats at the local parish church. Further, Mr. Parry felt that a lot of people just didn’t seem to need the church.This provoked a very lively discussion and the majority of members present raised their voices and opinions regarding the apparent falling off and decline in church congregations.

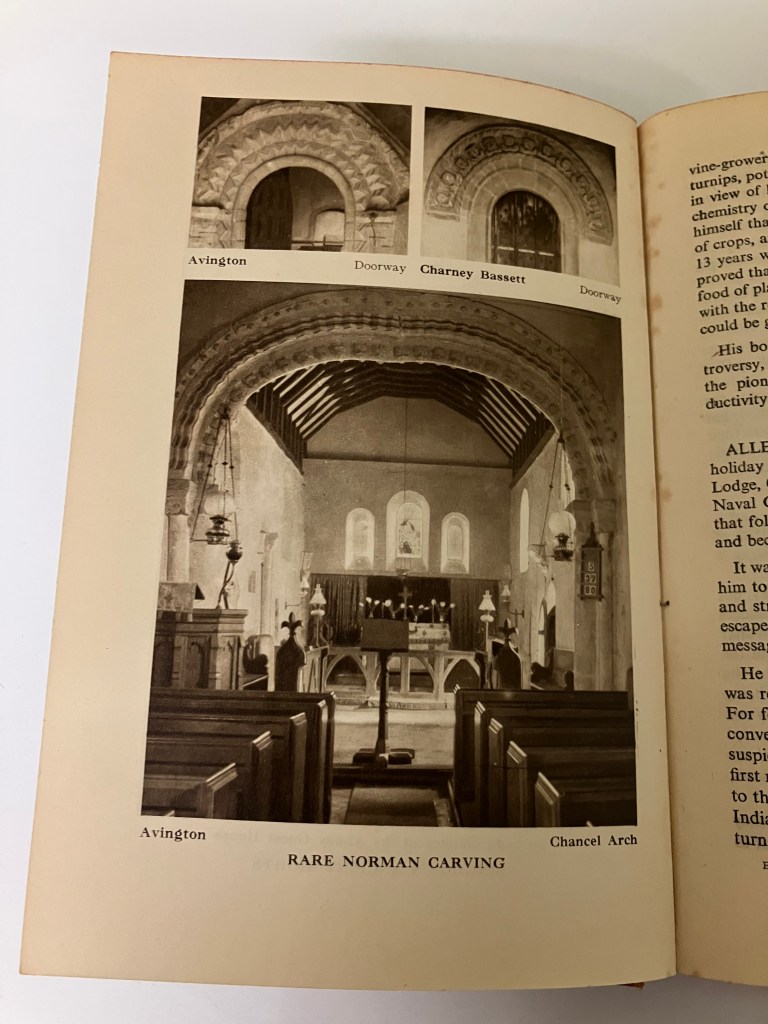

The next talk was to be given by the vicar on ‘Church Architecture’ causing a Mr. O’Rourke to comment, ‘From Flying Saucers to Flying Buttresses’.

The meeting concluded with Mr. Palmer inviting members back to his home for cups of tea. Despite being newly decorated, the Parish Room did not have mod cons and refreshments could not be catered for.

A committee meeting in March brought forth suggestions for future gatherings. Some topics under consideration were of a seriously religious nature and included a Clarification of The Creed in Three parts, and a further two talks by the ever- popular Sidney Inns. However other suggestions were more topical and concerned contemporary issues such as, ‘Does the Welfare State Make for Better People?’, ‘Education Today,’ ‘Love Thine Enemy’, ‘Blood Sports’, ‘Local Government’, and ‘Trades Unions.’

It seems the men of Kintbury did not shirk from a subject because it might upset someone, put them off church, or create tensions. Lively debates took place and there was what might be called a ‘frank exchange of views’.

In March, 1957, the Bishop of Reading wrote to the Fellowship telling them of a meeting in Reading to be addressed by the Bishop of Coventry and titled, “Operation Firm Faith”. It was hoped that 2,000 men would attend although it seems that women were not invited.

In the event over 1,000 men turned up and were, apparently, held in the palm of the Bishop’s hand as he convinced them of the joy of being a Christian. Five points, he said, needed to be practised and the churches would be filled to over flowing. The points were Go Out, Stay Out, Think Out, Speak Out, Live Out.

This stirring meeting ended with the singing of Jerusalem and the minutes say that ‘words cannot describe the harmony of sound produced by so many male voices’.

There might also have been harmonious voices at the Annual General Meeting in May. It was a glorious evening and members set out to a private room in the Red House. There were abundant refreshments and a private bar. The title for the evening was; ‘Thirst after Righteousness’. The minutes record that, with regard to suggestions for the coming year, one suggestion, ‘Is beer our favourite beverage’? was no doubt prompted by the proximity of the beverage – the Red House was – and still is – a pub. The rest of the evening was devoted to general good will and the vicar soared to the heights of comedy by his presentation of Norfolk rustic life.

The following meeting was devoted to ‘Does the Welfare State make for Better People’? Speaking in favour, Mr. Cummings thought that education enabled people to choose their way of life rather than follow like sheep and be fearful of the consequences as happened in ‘the good old days’. Mr. Jones, opposing, felt that the Welfare State brought about a selfish outlook on life and mentioned that in eastern countries it was honourable to care for one’s parents in old age. The ensuing discussion was ‘most enlightening and many controversial facts were raised tho’ politics did not intervene.‘ It was thought that it would make interesting reading to have a similar discussion in fifty years time.

The spring of 1957 had seen the publication of the Wolfended Report which recommended that homosexual acts between two consenting adults should no longer be a criminal offence. At the time this was a contentious issues but the Men’s Fellowship did not shy away from it and the report was discussed at the April meeting. Question time produced many interesting items but they were evidently considered too risqué to record in the minutes. So what the men of the Kintbury Fellowship thought about this proposed change in the law, we shall never know.

January 1958 was devoted to a very touchy subject for a rural parish: Should Blood Sports be Abolished? Mr. Bob Sanders spoke about his boyhood in Devon and the damage that a stag and his harem can do to crops. Hunting, he said, was nature’s way of controlling vermin. Mr. R. Westcott proposed the motion and although secretly he agreed with hunting, from his vehemence one would have thought that all hunters and hounds should be boiled in oil. Hunting, he said, was a form of sadism in a civilised world. He ended by announcing that if the meeting voted to retain bloodsports they would all leave the meeting forever branded as sadists! Controversial stuff for a village.

Despite this ominous note members did condemn themselves by voting for retention which was probably not surprising

The following talk, once again by popular speaker Sidney Inns, was on a completely different – and much lighter – subject: Superstitions. Sidney explained the significance of different numbers and why horse shoes were considered to bring luck.

In May a touch of the exotic was introduced when Mr. Parry brought along his guest, Mr. Mohammed El Amin Ghabshawi, who was wearing the national costume of the Sudan. He explained the history of the Sudan and spoke with enormous enthusiasm about his country. The Sudanese government, he said, was friendly to all and welcomed foreign capital investment. It is rather sad in view of all that has happened since to read that the overall picture gained was that ‘here was a people who were striving in the right ways to improve their economy and by their general attitude to all other nations might very well attain a very high standard of living in the not too distant future.‘

The speaker in March 1959 was happy to express views that very few would concur with today. This was the era of apartheid in South Africa and the subject was inspired by a cutting from the Sunday Times in which the Prime Minister, Harold MacMillan, said that the South Africans were making a grave mistake in handling racial affairs.

The speaker, a Mr. Wallace, expressed some very controversial opinions which today would seem prejudiced and ill-informed. He said that he had not been in South Africa but he knew the Africans and had employed some of them on his farm. The word ‘freedom’ was being shouted by all Africans and they were becoming very unruly, in his opinion. He did not see what cause they had for shouting this as they had been given many freedoms. For example freedom from slaughter by other tribes and freedom from fear of being sold as slaves. He went on to say that he did not want any mixed race marriages and who really would? Africans, he believed, only understood harsh rulings and were much better off now than one hundred years ago all due to the whites.

Mr Wallace concluded by asking if anyone had any questions or comments. Mr. Inns then asked if witchcraft was still practised. Mr Wallace said that it was and that one of his farmworkers had died when cursed. He finished by saying that the proposed international boycott of South African goods was stupid.

The minutes do not record what the men of the Christian Fellowship thought about Mr Wallace’s hard line opinions.

Meetings continued into the early 1960s and Sidney Inns’ faith themed talks were still popular. In his next talk, Sid gave a brief description of four major religions in which he included – rather surprisingly – Mithraism along with Hinduism, Buddhism and Islam.

The recently published New English Bible – the New Testament of which had been published in 1961 – was, not surprisingly, a topic for discussion and the men were informed by a speaker that the new version was now listened to with more interest than the “King James” version of 1611.

These were the days before the Church of England updated its forms of service and the Book of Common Prayer of 1662 was the most frequently used. Opinions were expressed that the service of matins was very hard to understand particularly for the younger generation and a “Family Communion” in which all share would be easier to understand.

Other reforming ideas were discussed and during one of the periodic ‘Any Questions’ it was decided that it was a good idea, within certain limits, for priests to work side by side with factory workers and get the gospel to them that way. However, the right man ( no women priests back then, of course ) for the job must be found who should be very careful in his manner of approach.

Reforming suggestions continued to be discussed with the proposal – radical to some – that the appointment of a vicar to a living for life would no longer continue –led to a very lively discussion, opinions being divided more or less equally on most points.

Meetings continued throughout the 1960s. One topic that was perhaps surprising for a Christian fellowship was Psychic Research. Canon Harmon, vicar of Froxfield spoke about the nature of the mind, spirit, soul, telepathy and visions. Jesus, he believed, had psycho kinetic powers and examples of this were shown in His miracles. Canon Harmon was so interesting that he was invited back again and in his second visit gave examples of séances, materialisations and the return of departed spirits.

The Fellowship finally demised in the early seventies by which time some subjects under discussion had become a little more political. One of the last topics to be discussed was the war in Vietnam and the justification, or otherwise, of American intervention.

The Kintbury Men’s fellowship was obviously of its time. It is difficult to imagine that so openly racist views as held by Mr. Wallace in 1959 being allowed to go unchallenged today although the topic of bloodsports would still divide opinion. However, over sixty years later, “Does the Welfare State make for better people” might still prove to be a topic for an interesting debate.

© Penelope Fletcher 2024