We have, I believe, just one description of Jane Austen’s appearance, recalled by someone who knew her well all her life – someone who had known her since she was a small child of three.

“She was like a doll……certainly pretty – bright and a good deal of colour in her face – like a doll – no, that would not give at all the right idea for she had so much expression – she was like a child – quite a child, very lively and full of humour.”

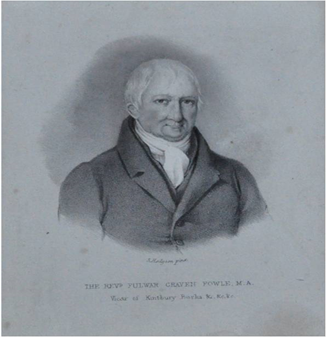

That person was Kintbury’s vicar, Rev Fulwar Craven Fowle.

Fulwar ( pronounced “Fuller” – it was a family name ) was born in Kintbury on June 12th 1764, the eldest son of Rev Thomas Fowle and his wife, Jane née Craven. These were the days when having connections, either within the family or otherwise, could lead to appointment to a parish; in the case of the Fowles, Fulwar’s grandfather Thomas Fowle I had been appointed vicar of Kintbury in 1741 and his father, Thomas Fowle II, followed him in the post from 1762 to 1806.

At the time, it was not at all uncommon for a priest to hold the position of rector in other parishes. Thomas II was rector of Hamstead Marshall, not far from Kintbury, and also Allington, near Salisbury in Wiltshire. Later, as well as being vicar of Kintbury, Fulwar himself was also rector of Elkstone in Gloucestershire.

So the Fowles could be said to have been very much a family of the vicarage. This was a time when vicarages, wherever they were, were larger, higher status houses and those who lived in them led relatively comfortable lives supported by servants and other staff. However, a vicarage life was not associated with opulence and none could be described as stately.

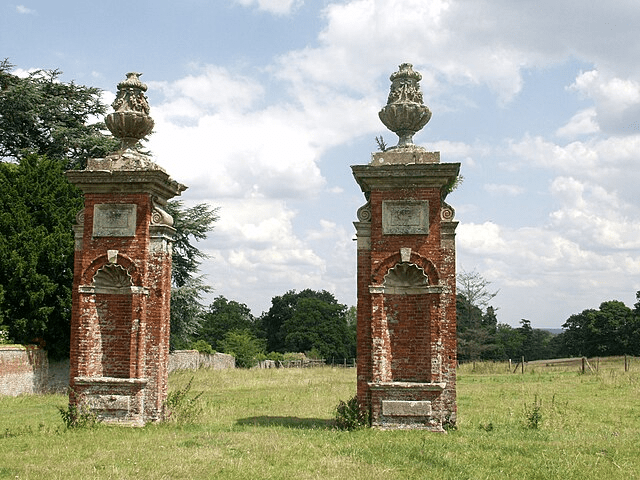

By contrast, the Cravens’ seat at Hamstead Marshall, three miles to the east of Kintbury, was far grander.

Fulwar’s mother Jane Craven was born in 1727, the second daughter of Charles Craven and his wife, Elizabeth Staples of Hamstead Marshall. Charles is better known as “Governor Craven” from his time as being governor of South Carolina in America. The former Elizabeth Staples has a reputation as a socialite with little time for her family.

When Charles Craven had been growing up, the Craven family seat was the elegant baroque mansion in Hamstead Park, designed by the Dutch architect Balthazar Gerbier in the mid C17th. Unfortunately, this building burnt down in 1718 and by the time of Charles Craven’s marriage to Elizabeth Staples in 1720, it is likely that the family home was an extended hunting lodge on the estate.

So, even though the Hamstead Marshall Cravens no longer had a “stately” house, they did have a high status home and close family links to the Earls of Craven, such that Jane Craven’s family could be said to occupy a higher rung on the social ladder than that of the Fowles.

Jane & Thomas were married at Kintbury on July 18th, 1763. Jane was 36 and Thomas was 37. Thomas had been ordained priest the previous year and became vicar of Kintbury following his father’s recent death and the post becoming vacant. Perhaps the comparatively later age at which the couple married could suggest that their marriage was not economically viable until then, despite Jane’s family having been wealthy. We do not know.

Thomas & Jane had four sons: Fulwar Craven, born 1764, was followed by Thomas, born 1765, then William, born 1767, and finally Charles, born 1770.

Fulwar was a fair-haired, blue-eyed child, slight of stature and never very tall, even in adulthood. The country side would have encroached on the village of Kintbury more so than it does today, enabling the Fowle boys and their friends to roam at will and swim in the Kennet. Like all of the more comfortably off, the boys would have learnt to ride as a matter of course and by adulthood, Fulwar had the reputation of being a very good horseman.

We can assume that, whilst life in the Kintbury vicarage might not have been opulent, it would have been economically secure particularly when compared to the lives of many working people and farm labourers in the cottages of Kintbury.

There was no universal education in late eighteenth century England. In some towns and villages a basic education was offered by religious or charity groups and there were well-established grammar schools in more prosperous towns which prepared young men for the professions or university entry. For the sons of wealthier families there was a choice of “public” schools – a misnomer in that these schools were – and are – expensively fee-paying and elitist.

The novel, “Tom Brown’s School Days”, published in 1857, is a fictionalised account of being a pupil at Rugby, a public school in the south east midlands, in the 1830s. Its author, Thomas Hughes, was the grandson of the vicar at Uffington, then in Berkshire, across the downs around twenty miles to the north of Kintbury.

It might be assumed that, coming from a similar background, the Fowle sons would also have attended a public school, perhaps Eton, close to Windsor in east Berkshire, or Winchester, in Hampshire. Instead, Jane and Thomas chose to send their sons to the school run by Rev George Austen and his wife, at Steventon, near Basingstoke in Hampshire. George Austen’s “school” was actually in the family home – the Steventon vicarage.

Thomas Fowle had known George Austen since their days at Oxford University so perhaps he felt more comfortable entrusting his sons’ education to someone he knew very well. Alternatively the costs of a public school education might have been beyond the budget of a rural parson, we cannot say. The reality might have been a combination of both factors.

We do not know precisely the curriculum Rev Austen would have offered his students although it would very likely have centred on the Classics – Latin and Greek- which would prepare the boys for further study of the same at Oxford University.

Fulwar was fourteen when he first joined the other borders at the Steventon vicarage school. At that time the Austens’ eldest son, James, was nearest to Fulwar in age and became his closest friend. Edward was 11, Henry 7, Cassandra 5 and Francis 4. The baby of the family at that time was Jane, aged 3. Charles was to arrive a year later.

It goes without saying that the Austens would have had servants; however, even with help with cooking, cleaning and laundry, the household must have been a particularly busy one. One can only assume that George Austen’s wife, Cassandra, must have been a particularly well-organise and relaxed person – laid-back, we might say today – to run such a household.

Fulwar’s brothers later joined him at Steventon: Tom in 1779 and William and Charles sometime in the early 1780s. The young Austens also visited Kintbury, and many years later, in 1812, James Austen wrote a poem in which he recalled staying at the Fowles’ home in Kintbury:

And still in my mind’s eye methinks I see

The village pastor’s cheerful family.

The father grave, but oft with humour dry

Producing the quaint jest or shrewd reply;

The busy bustling mother who like Eve

Would ever and anon the circle leave

Her mind on hospitable thoughts intent

Careful domestic blunders to prevent.

Whilst James Austen was clearly not a second Wordsworth, his words suggest the Fowles were a warm, happy family. Perhaps the “humour dry” and “quaint jest” suggest that the Austens & Fowles shared a common sense of humour or enjoyed the same sort of witticisms. Perhaps both families would a have agreed with Jane Austen’s Mr Bennett when he said,

“For what do we live, but to make sport for our neighbours, and laugh at them in our turn?”

There is certainly evidence that Fulwar had an acerbic sense of humour, which is perhaps not surprising in a close friend of the Austens.

At Steventon, all the Fowle brothers were successful students. Fulwar went on to enter St John’s College, Oxford in 1871 where he gained a BA in 1785 and an MA in 1788. His brother, Thomas went up to Oxford in 1783 and gained an MA in 1794. William went on to study medicine ( not yet a subject taught in an English university ) as an apprentice to his uncle William Fowle in London. Charles studied law and was called to the bar in 1800, later practising law in Newbury.

Perhaps it was inevitable that Fulwar would follow his father and grandfather into the church; in 1786 he was ordained deacon at Salisbury cathedral and was installed curate of St Mary’s, Hamstead Marshall on the following Christmas Eve. It has to be very likely that he obtained this post due to family patronage, which, at this time, would have seemed perfectly normal and acceptable with no accusation of nepotism.

Also in the manner of the time, Fulwar became rector of Elkstone in Gloucestershire in 1788 where the manor had belonged to the Craven family since 1623. 0nce again an example of an appointment made as a result of family connections.

1788 was also the year in which Fulwar married his cousin, Elizabeth – known as Eliza – Lloyd. Eliza’s mother was the former Martha Craven, daughter of Governor Craven of Hamstead Marshall. Martha had married the Rev Noyes Lloyd, vicar of Enborne in 1763 and Eliza, along with her sisters, Martha & Mary, with their brother Charles, had grown up there. Sadly, Charles died in 1775 following an outbreak of smallpox.

In Elkstone, the elegant, three storey rectory built earlier in the century became Eliza & Fulwar’s family home for the first six years of their marriage. Their first child, however, Fulwar William, was born at Deane, near Basingstoke in Hampshire in 1791. It has to be likely that this was because Eliza’s mother and her sisters Mary & Martha had been living there since having to vacate Enborne vicarage on the death of Rev Nowes Lloyd in 1789. As a first-time mother, Eliza probably wanted her confinement to be somewhere close to her family for support.

The couple’s second child, Mary Jane, was born at Elkstone in 1792 although the baptism of their third child, Thomas, in 1793, is recorded as being in Hurstbourne Tarrant, near Andover in Hampshire. Although it is a very long way from Elkstone, Eliza’s mother and sisters were now living at Ibstone, a hamlet close to Hurstbourne Tarrant so it would be logical to assume Eliza had once more returned to her family for her confinement.

In 1794 the family returned to Kintbury where Fulwar took over the incumbency. By now there were two more children: Mary Jane, had been born in Elkstone in 1792 & Thomas in Hurstbourne Tarrant in 1793.

Caroline Elizabeth had been born in December of 1794 but died the following January. Both her baptism and death are recorded as being at Hurstbourne Tarrant.

In January 1797 a happier event occurred at Hurstbourne Tarrant where Eliza’s sisters Mary & Martha were still living with their mother. Mary Lloyd married the widowed James Austen and became step-mother to James’ daughter Anna. In the custom of the time, Eliza Fowle could now speak of James Austen as her brother. Martha Lloyd was to become one of Jane Austen’s closest friends and a life-long companion.

However, tragedy was soon to strike the extended family.

In 1795, Fulwar’s brother Tom Fowle had become engaged in secret to Cassandra Austen prior to joining an expedition to the West Indies as Lord Craven’s chaplain. However, he was never to return and news of his death from yellow fever reached Kintbury in the February of 1797. It was James and Mary who broke the news to Cassandra.

Over the next eight years four more children were born to Fulwar and Eliza in the Kintbury vicarage. In a letter to Cassandra of December 1st, 1798 Jane Austen wrote,

“No news from Kintbury yet – Eliza sports with our impatience.”

It is worth remembering that this was a time when everyone would have known someone who had died in childbirth so Jane Austen’s wry humour would be masking a real concern for Eliza’s welfare. Elizabeth Caroline ( known as Caroline ) arrived five days later on December 6th. She was christened in Kintbury on January 19th by James Austen.

Isabella followed in 1799, Charles in 1804 and Henry in 1807.

The Fowles, the Lloyds and the Austens remained friends throughout their lives. The little girl Fulwar had first got to know in the Steventon vicarage had shown a prodigious talent for writing and become a very succesful novelist. In 1815 the Prince Regent even requested that Jane should dedicate her latest novel to him, which she did. As it happens that novel was Emma, the one about which Fulwar famously said he would only read the first and the last chapters as he had heard it wasn’t interesting. I very much doubt that Jane would have been particularly offended by this comment – after all, she knew him almost as well as she knew her older brothers, and for almost as long.

Despite the disparaging comments about Emma, we know that Fulwar did indeed purchase other of Jane’s novels, as copies with his name, written in his handwriting on the title pages, have fairly recently come up for auction. We know from Jane’s letters that Eliza bought a copy of Sense & Sensibility.

Throughout this time there are many passing references to Fulwar & Eliza in the letters of Jane Austen. However the most telling reference as regards Fulwar is that January 1801. In her letter to Cassandra, Jane writes:

“We played at vingt-un, which, as Fulwar was unsuccessful, gave him an opportunity of exposing himself as usual.”

Fulwar, it seems , was not good at hiding his bad temper. But by this time Jane had known him for over twenty five years and must have been very well aware of his moods.

As their priest, Fulwar Craven Fowle served the people of Kintbury for the rest of his life. Whilst not all Anglican clergy were in any way wealthy and some seem just to have been scratching a living in their parishes – (indeed it is believed one of the reasons why the ill-fated Rev Thomas Fowle took the post of Chaplain to Lord Craven’s expedition was to raise enough money to marry Cassandra ) – all the evidence suggests that the Fowles’ life in Kintbury was secure and comfortable.

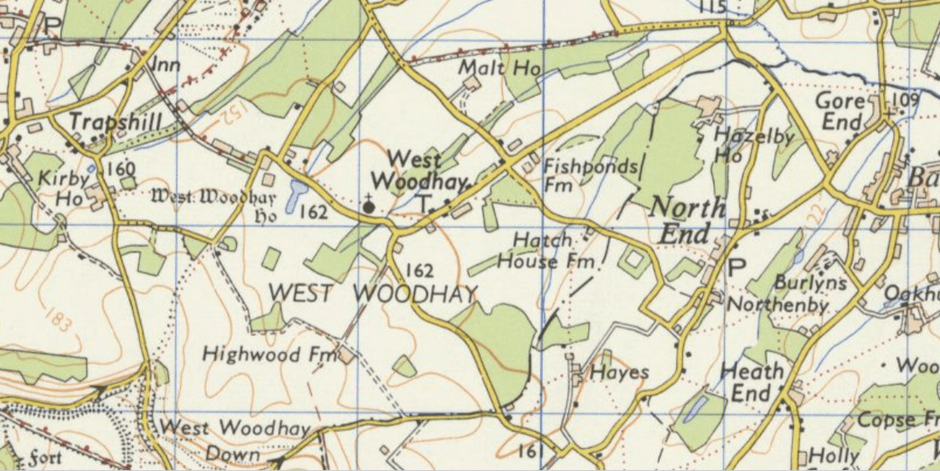

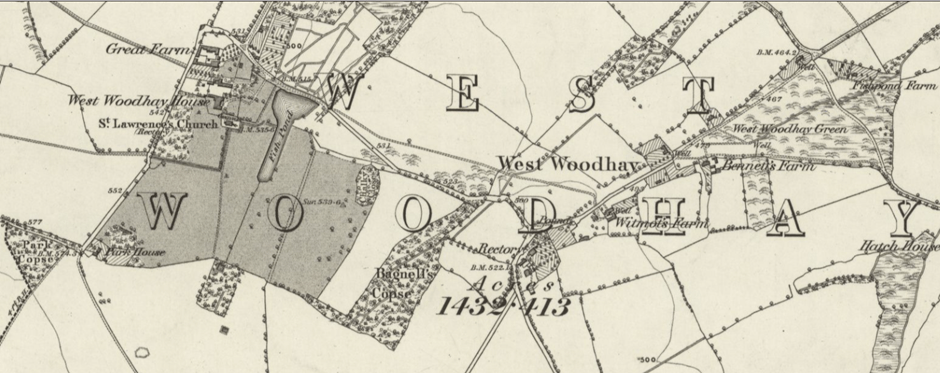

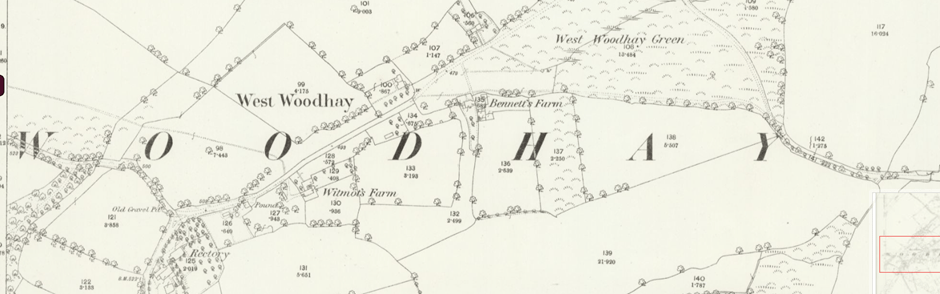

As well as carrying out his duties as parish priest in Kintbury and, from time to time visiting the parish of Elkstone, Fulwar was very much involved in West Berkshire public life.

In 1805 he was appointed Lieutenant Colonel Commandant of the Kintbury Rifle Corps and in the same year led the local Volunteer Brigade to Bulmersh, near Reading where they and other volunteer regiments were inspected by George III. Apparently the King was particularly impressed by the “military perfection” of the Berkshire Volunteers and with Rev Fowle as their officer.

I think it’s worth remembering that at this time there was still the threat of invasion from the French under Napoleon across the channel and the south coast felt particularly vulnerable. Having an efficient volunteer force was important to the nation’s security in the same way as the Home Guard was in the Second World War.

Despite the country being on a war footing and the newspapers continuing to carry reports of Napoleon, daily life continued relatively uninterrupted.

It seems that Rev Fowle moved within what Jane Austen’s Mrs Elton would have described as “the first circle” socially. According to a newspaper report of 1807, for example, he was one of several dignitaries to attend a race meeting at Enborne Heath near Newbury. Others named include the Earl of Craven and Sir Joseph Andrews of Shaw House, Newbury. Very much the local “great and good”.

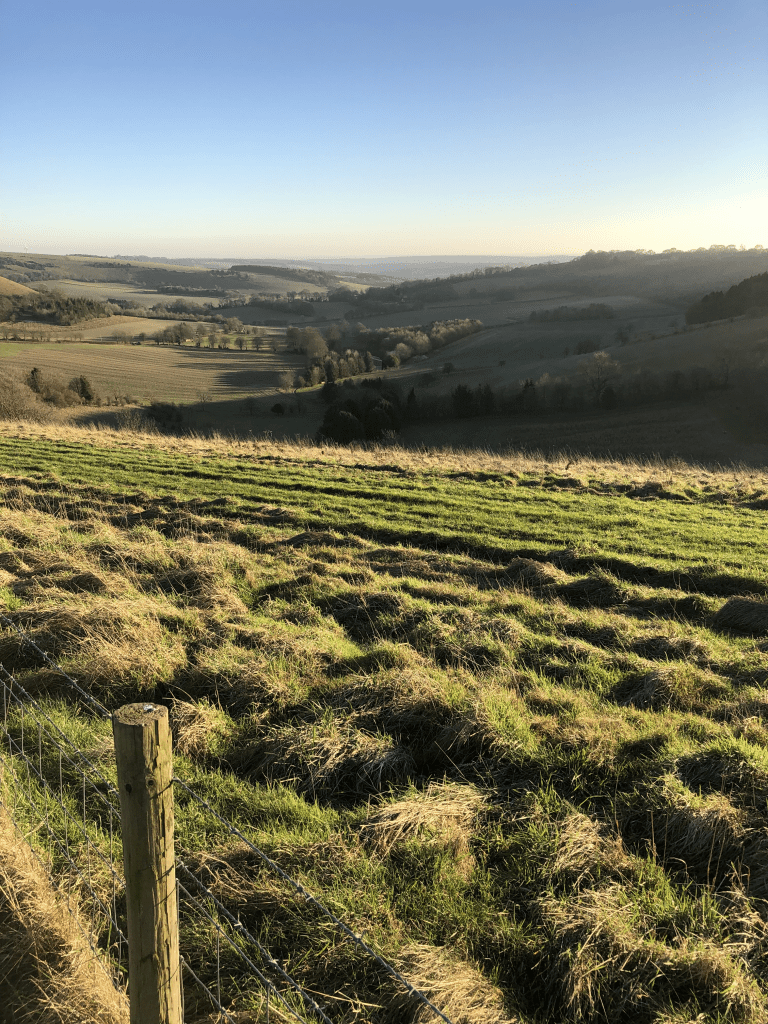

What is perhaps surprising is the amount of property and land that Fulwar owned in the area. This included 55 acres of farm land, two cottages and other farm buildings at Rooks’ Nest farm just south of Kintbury, and also 350 acres of pasture and arable land with adjoining farm house and other buildings at East Woodhay, just over the border in Hampshire.

However, Fulwar does seem to have taken an interest in agriculture and was not simply a landowner who cared solely about collecting the rent. In 1808 he was elected Steward of the Berkshire Agricultural Society for that year and in 1820 became a member of the Hampshire Agricultural Society

This was the time of what is now known as the agricultural revolution – the period throughout the late eighteenth century into the nineteenth century when many landowners and working farmers were developing ways to increase agricultural production. In this area, South Downs and Merinos were the breeds of sheep most commonly kept by farmers but at the Hampshire Agricultural Show of 1820 the Rev Fowle exhibited a pen of Leicesters which, “excited much attention” as they had not been seen there before. Furthermore, the superior weight gain of these sheep, when compared to that of the usual breeds, was due, it was believed, to their having been fed on a diet of “sliced Swedish turnips” rather than corn and cake. Over the next two years, the Leicesters maintained their advantage when reared under controlled conditions.

Whilst it has to be likely that it was a shepherd in Rev Fowle’s employment who would have undertaken all the husbandry involved in this experiment, Fulwar himself must have approved of its happening and may well have initiated it.

The Agricultural Revolution resulted in a slow and relatively peaceful change throughout the country. The same could not have been said about the French Revolution, observed from across the channel, where social change had included the violent removal of the monarchy and aristocracy. Throughout Fulwar’s life there were campaigns for social and political reform across the country but these were accompanied by fears, on the part of the establishment, of the kind of violence that had been seen in France. I think it is in the light of such fears that we need to assess the response of certain authorities to the unrest that broke out across southern England in 1830, though it does not excuse the more extreme reactions.

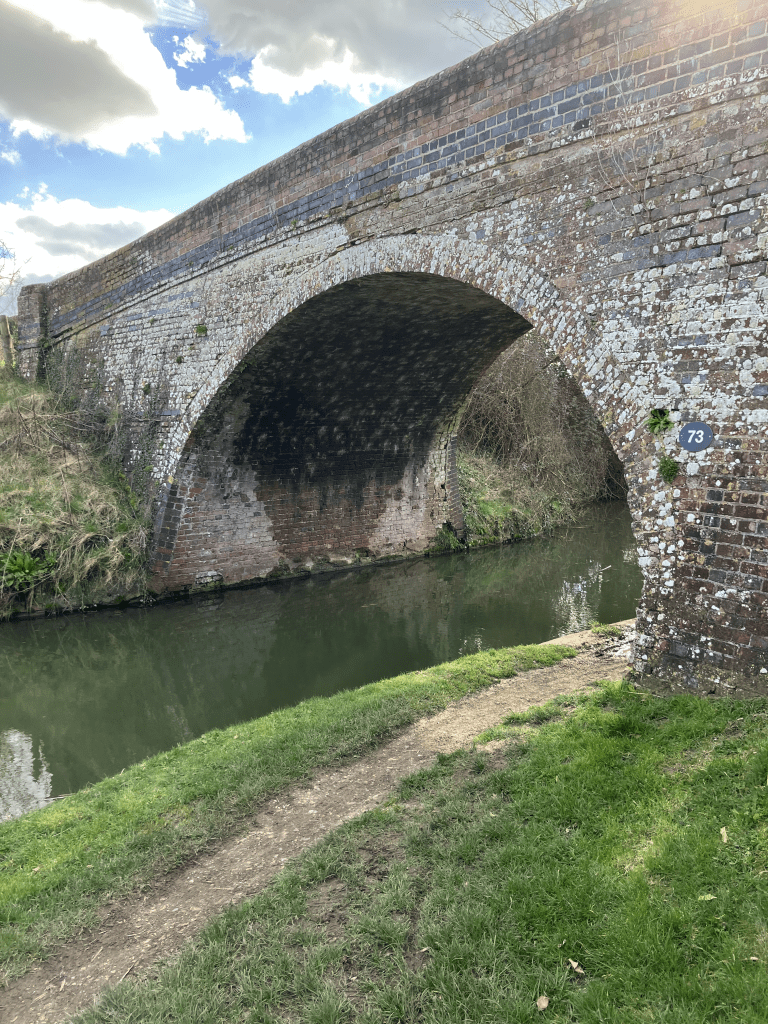

By 1830, Fulwar was 66 and Eliza 65. The couple still lived in the vicarage: the white building next to the River Kennet where Fulwar had grown up although now its garden formed part of the south bank of the Kennet & Avon canal as it flowed towards Kintbury wharf, bringing coal and other commodities to the village.

Fulwar also served as a magistrate and was, therefore, regarded as a figure of authority and most probably of derision on the part of those who came before the bench. Such is human nature. He seems to have been respected and held in affection by the members of his church; by now, however, Kintbury had both a Methodist church and a Primitive Methodist church so numbers of nonconformists in the village would not have been inconsiderable: Rev Fowle was not everyone’s priest.

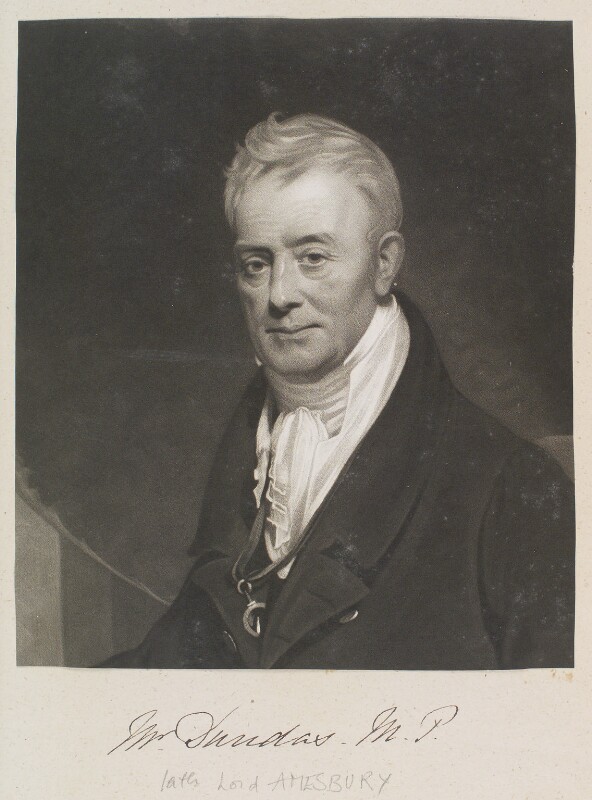

Their neighbour, 79 year old Charles Dundas still had his seat at Barton Court, less than half a mile along the coaching road which led from the Bath Road into the village. Dundas had been Member of Parliament for Berkshire since 1794.

We have written quite extensively in this blog about the events which led up to the Swing Riots of 1830. Formore information you might like to look at these articles: The Kintbury Martyr parts 1, 2 and 3.

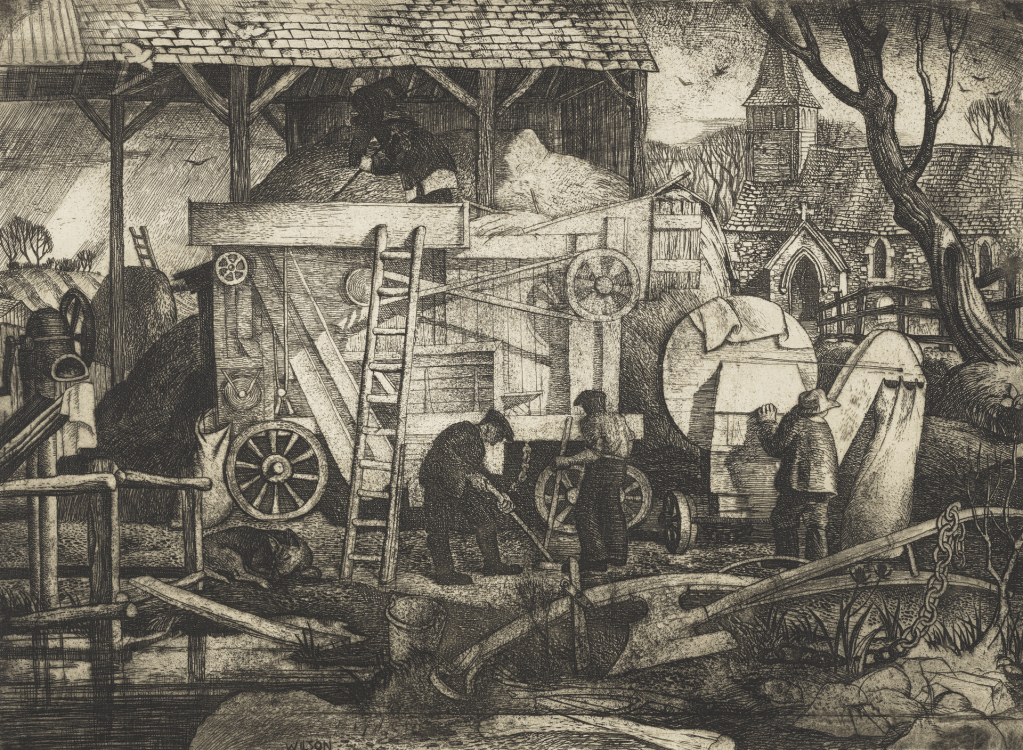

Following a year of escalating hardships, by the autumn of 1830 the agricultural labourers focussed their attention on threshing machine: the mechanical devices that could do the work of several men at a time rendering them redundant when their casual employment was most crucial if they were to earn enough to feed their families through the upcoming winter. By the night of November 21st of that year, a riotous mob of angry men was roaming through the local villages, demanding money from the farmers and threatening to set fires and smash machinery, in particular the hated threshing machines.

Thanks to a letter held by the National Archives we can read Fulwar’s own account of what happened when the Kintbury mob arrived at the vicarage. Apart from some of his sermons, the letter is the only time we can hear his voice through his writing – writing that is small and neat despite the strain of the night he has just witnessed. He frequently punctuates by using dashes. Both the neatness, much of the letter formations and the dashes are reminiscent of Jane Austen’s letter writing, which leads me to wonder if both were influenced by George Austen. It’s a thought.

The letter opens:

Dear Dundas,

The mob continued their work of breaking machines the whole of the night. They came to me about 4 oC in the morning. Harrison consulted with me and I agreed with him that it would be better to bring your machines to Kintbury and let them break them there than that they should go to BC for that purpose. They were brought up accordingly and taken into the street.

I think it is important to remember that at this time there was no police force and no authority that the Fowles could have called upon easily had they felt threatened. We do not know if anyone else was living at the vicarage besides Fulwar and Eliza – there may well have been one or two domestic servants and we know that Fulwar had a gun licence but all the same the couple would have been aware that they had very little personal protection had the mob turned violently against them.

Fulwar’s tone is resigned with acceptance of the situation rather than anger. He is clearly being kept informed of developments, telling Dundas that the mob has moved on to Titcombe, Hungerford Park and North Hidden, intending to go further. If this is correct, the rioters must have been moving swiftly through the area to have covered the distance. Furthermore, someone – or perhaps several people – must have been following on horseback to be able to report back as to what was happening. In these days of radio or mobile phone communication, it is easy to forget just how difficult it must have been in 1830 to follow what was happening.

The rioters have been demanding money:

I understand that they will have two pounds from each person; I know they had two from me, from Johnson, Captain Dunn and Mr Alderman.

According to the Bank of England online inflation calculator, £2 in 1830 equates to £199.40 today.

Once more I find Fulwar’s tone interesting – he is accepting of the situation and, at this time at least, offers no criticism or disapprobation.

I have not heard that they have committed personal violence on anyone rather than forcing the labourers to join them. Ploughs with cast iron shears appear to me as much the object of their hatred as machines and these they have broken many.

It is obviously important to Fulwar that he points out to Dundas that the rioters have not been personally violent to anyone and that the labourers ( by which I understand those not originally part of the “mob” ) are being forced to join in. Today we might speak of these people as being radicalised by the original protesters.

Further details are being brought to the vicarage as Fulwar writes:

I have just received a message from Mr Willes that the different parties have joined at Hungerford and exceed 1000 men.

One thousand men. That is half the population of modern day Kintbury. Even if that number is an exaggeration, a mob of even 250 angry men would be very frightening.

Fulwar continues to add to his letter as further information is brought to him. The Hungerford and Kintbury men have met with Mr Pearce ( a farmer ) and Mr Willes ( John Willes, JP of Hungerford Park ) and others. The men were demanding:

… twelve shillings a week for a man & wife & three children & the price of a gallon loaf for every child above three – these terms were acceded to by the Gentlemen as far as they could be, they were to be recommended for adoption to the farmers. I hope they will aceede (sic) to them I am in momentary expectation of being sent for by the Kintbury men who are returned or just returning to the village. I cannot of course try to beat them down to a lower price. These loaves to the children are all that men in health are to have from the parish as I understand these Gentlemen

According to the Bank of England, twelve shillings in 1830 equates to £59.82 today. The price of a gallon loaf in Newbury varied between one shilling and seven pence and one shilling and nine pence, so something around £8 today.

Fulwar concludes his letter at this point, then adds a post script:

I have just met the men – they (missing text) the same terms which had been agreed at Hungerford and I told them that as far as was in my power I would endeavour to persuade the farmers to agree to them. The men gave three cheers and expressed themselves perfectly satisfied but they all agreed that there must be no payment in bread but all in money. I could not feel justified in bringing back angry feelings by refusing to promise to recommend that also.

Fulwar’s tone in this letter is undoubtedly conciliatory. Whilst he admits that he does not want to bring back angry feelings, I don’t believe he was merely seeming to be sympathetic to the demands because the men are threatening.

Unfortunately, not everyone was in agreement with the way Fulwar dealt with the mob, believing him to be too much in sympathy with them and encouraging them. Someone complained to Lord Melbourne, the Home Secretary, and as a result, Charles Dundas and over ninety other villagers signed a letter to Melbourne, assuring him that Rev Fowle had done everything he could to quieten the disturbances.

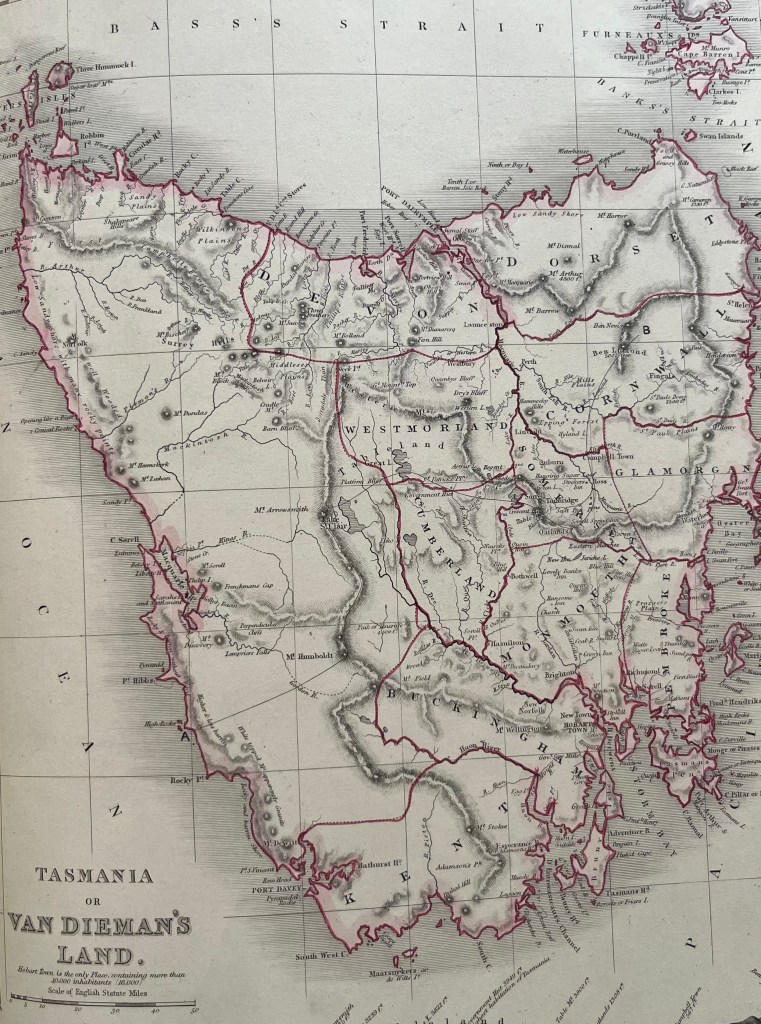

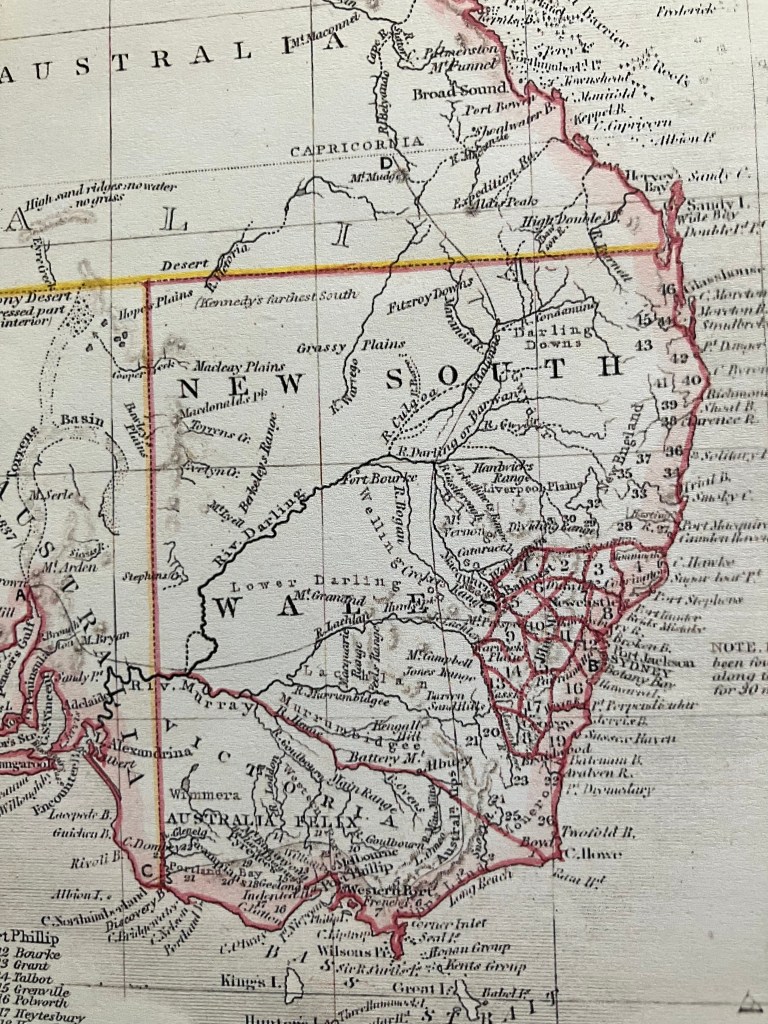

Despite Fulwar’s attempts, the wider disturbances did not end there and then at the Kintbury vicarage, as we have written about elsewhere on this blog. The resulting court case was eventually heard at Reading the following January. Whilst several of the rioters were transported to Australia, just one man was executed: Kintbury’s William Winterbourne.

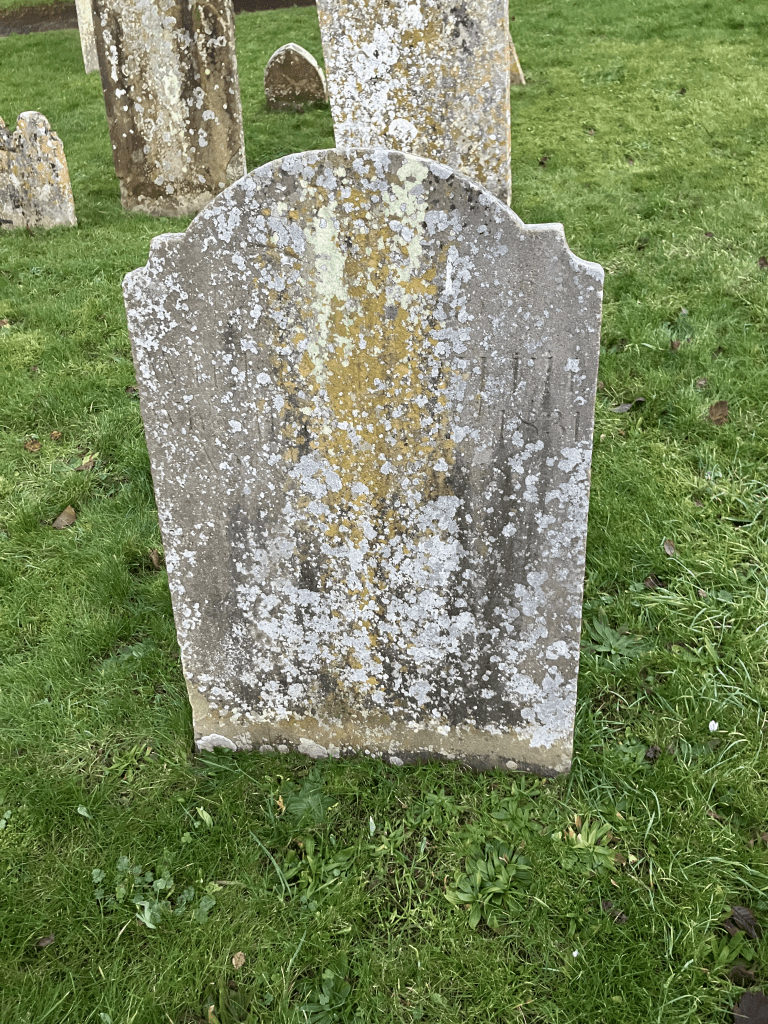

Winterbourne was hanged in Reading Gaol on January 11th 1831. Fulwar had his body returned to Kintbury where he was buried the next day in St Mary’s churchyard and later a grave stone erected. On the stone, Winterbourne is recorded as “William Smith” , Smith being his mother’s name and, as his parents were not married, it was the custom of the time to regard a child’s official surname to be that of the mother.

I think it is difficult for us today to appreciate how very unusual – indeed, practically unheard of – it was then for a labourer such as Winterbourne to have a grave stone. Such would be completely beyond the budget of poorer people and even skilled craftsmen and women and many who today we might consider to be “lower middle class” would not necessarily have a grave stone but be laid to rest in an unmarked plot. Rev Fowle was responsible for Winterbourne’s burial and grave stone in Kintbury churchyard and it would be interesting to know how the rest of the village reacted to what he did.

There has long been a persistent idea locally that Fulwar did this out of a feeling of guilt. I do not believe this to be so and there is absolutely no evidence, as far as I have been able to find, to suggest that Fulwar had any responsibility for the outcome of the trial or felt any guilt as a result of it. I believe his feelings would have been of extreme sorrow.

As a parish priest and also as a magistrate he was a figure of authority in a village where, in common with all of England at this time, everyone was expected to know their place in society, and stick within it. So, if he was known amongst many villagers as “Ol’ Fowle”, as some people believe, this does not signify any particular derision than that which would have been afforded to many other figures of authority or those who had agency over the working people.

On May 26th 1839, Eliza Fowle died at the Kintbury vicarage. She was 71. On March 9th of the following year, Fulwar also died. He was 75. His memorial, over the pulpit in the church describes him as: Pastor, Neighbour, Friend.

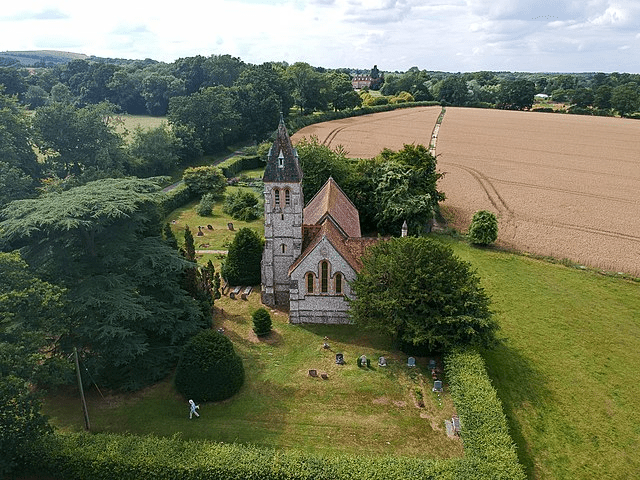

Fulwar’s death brought to an end nearly 100 years of the Fowle family as priests in Kintbury. Less than thirty years later, the white vicarage mentioned by James Austen in his poem, had gone, to be replaced by a then very fashionable neo gothic house which is still there today.

Elizabeth Caroline lived in Kintbury all her life. When Cassandra Austen died in 1845, she left £1000 and a shawl which had previously belonged to Mrs Jane Fowle to her. Very sadly, Elizabeth Caroline died in a London asylum in 1860.

Mary Jane Dexter, née Fowle, died in 1883 and Isabella Lidderdale, née Fowle, died in 1884, both in Kintbury.

On January 11th every year, people gather in Kintbury church yard to remember William Winterbourne/Smith, the Kintbury Martyr. But for Fulwar, Winterbourne’s grave would be in Reading, not here in Kintbury.

Throughout the year, Janeites ( as those who love the works of Jane Austen are called ) visit Kintbury because of her connections to the village through the Fowle family. Fulwar Craven Fowle is the link between what are often our very different parties of visitors.

And thanks to him we have this charming recollection of the woman he had known as a friend all her life:

” Like a doll……certainly pretty – bright and a good deal of colour in her face – like a doll – no, that would not give at all the right idea for she had so much expression – she was like a child – quite a child, very lively and full of humour.”

Sources:

Jane Austen’s Letters, collected and edited by Deirdre Le Faye, 1996

The National Archives

Ancestry

British Newspaper Archive

Adventuresinarchitecture.co.uk/tag/balthazar-gerbier

Elkstoneparish.gov.uk

National Library of Scotland OS map collection

Bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator

(C) Theresa A. Lock, 2025