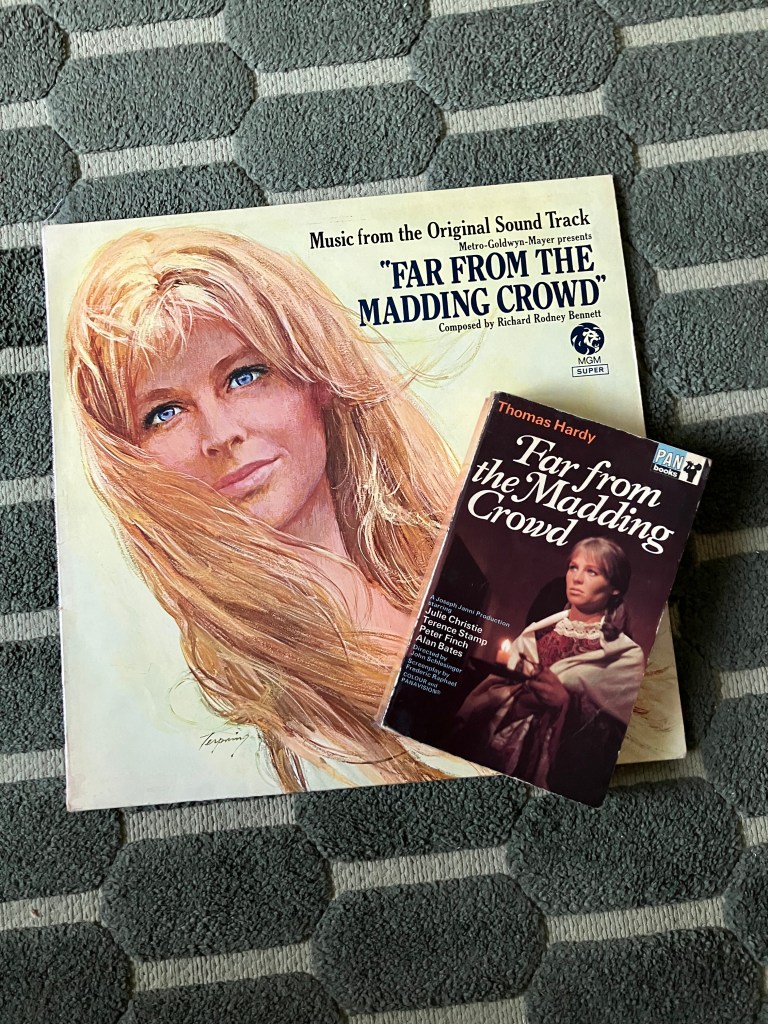

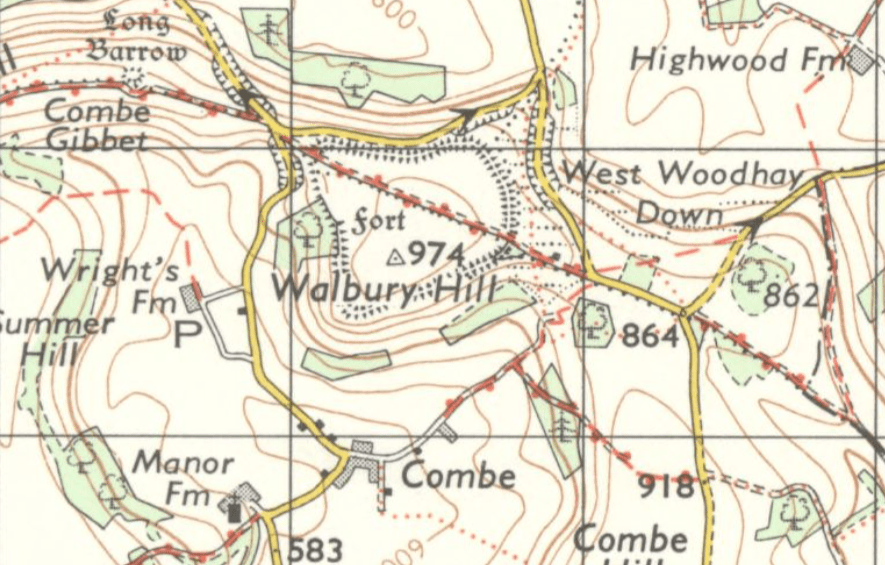

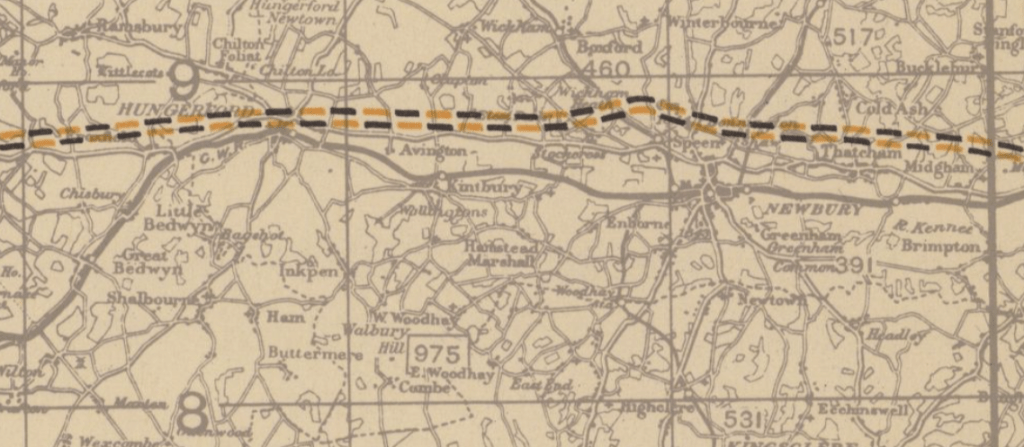

At present I am writing this as I look out at my garden on a particularly hot day. I am in Berkshire, or, if you prefer, Royal Berkshire. Less than three miles from my garden fence is Hampshire and I can look out of my bedroom window at Wiltshire. If I were to stand on my roof, I would see, three miles to the south, Walbury Hill, the highest point on chalk in England.

This wider area is often described as Central Southen England, although I like to think that, in our corner of West Berkshire, we look much more towards the west than towards Reading and the south east.

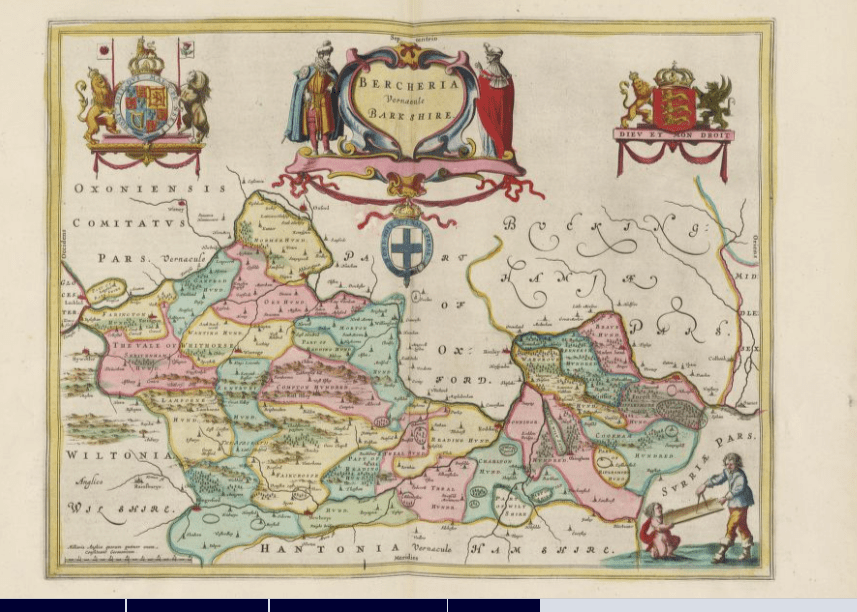

My local authority – the one responsible for emptying our bins, amongst other things – is West Berkshire, based in Newbury. Before 1998, when West Berkshire became a unitary authority, our local authority was Berkshire, based in Reading. The Berkshire, that is, which was considerably smaller than it had been before April 1974, when the Vale of the White Horse in the north of the old shire county was transferred to Oxfordshire, and Berkshire gained Slough, previously in Buckinghamshire.

Image:Nilfanion under Commons Licence, accessed from Wikimedia

Some people, with both a sense of history and also an ironic sense of humour, like to call the Vale, “occupied North Berkshire” – a nod to the feeling that Berkshire’s border with Oxfordshire should be along the Thames as it had been for hundreds of years.

However, very soon our local authority will be changing yet again. It may, although at the time of writing, this has not yet been confirmed, be known as Ridgeway, named for the prehistoric track that runs east to west across the Berkshire Downs. The Berkshire Downs, that is to say, the downs currently partly in Oxfordshire after Vale of White Horse – formerly in north Berkshire – was transferred to Oxfordshire following the local government reorganisation in 1974.

So, when – and if – we become “Ridgeway”, our devolved local authority will once more include the Vale, although people living there – for example in Uffington – will still be in Oxfordshire as far as their postal address is concerned. Furthermore, the Thames will once more become the border between our local authority and whatever the devolved authorites to the north are finally called.

Confusing? Definitely. But this is definitely not new.

To consider the long view – the very long view – we need to travel back in time over two thousand five hundred years to the Iron Age. The hill fort on Walbury Hill – which I mentioned in my opening paragraph -is home to people known to the Romans as the Atrebates. We will never know how they identified themselves because the Atrebates did not have a written culture but valued committing ideas and stories to memory instead.

If a man or woman from that hill fort were to stand on the highest point of Walbury Hill and look across the Kennet Valley, all the territory below would, perhaps reassuringly, belong to their tribe. In the far distance to the north west, was the territory of the Dobunni, and to the distant south, the Belgae. Of course there was no signage back then; no, “You are entering the territory of the Atrebates” although the locals may well have known that a particular river or ditch marked the boundary between Us and Them. Indeed, the very existance of a hill fort on a prominent ridge would have of itself made a statement visible for miles around.

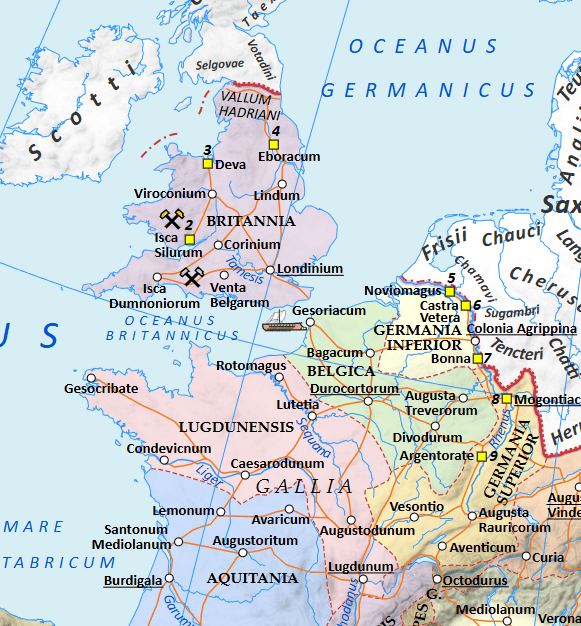

Map by Emil Reich. Under Commons Licence accessed from Wikimedia

Our area at the time of the Romans. Spinae may be modern day Speen and Cunetio is near modern day Marlborough

The arrival of the Romans in Britain around 55 BC brought some obvious changes. For the people of the Atrebates, their tribal centre at Calleva, ( modern day Silchester ) became an important Roman town. In the valley below Walbury Hill, the construction of the road to Aqua Sulis ( the Roman name for Bath ) would have seen an increase in traffic. Villas appeared in the landscape, as at Kintbury. Trade with the newcomers meant an increased variety of foods and other goods.

We do not know for sure if anyone was still living in the hill fort on Walbury Hill when the Romans arrived. We do not know, for sure, if any Iron Age man or woman, standing on the highest point on chalk in southern Britain, would have felt threatened by the increasing presence of the Romans in the valley below. We do know that it has to be likely that many Iron Age Celts continued to live pretty much as they had done before Caesar landed in Kent and continued to do so long after.

It may well be that, being impressed by the site of Roman soldiers marching through the valley below, young Iron Age Britons were persuaded to join up. As Roman soldiers and with the promise of Roman citizenship after a long period in military service, they would have identified as Roman. Perhaps they would have served in the north of the country or even abroad and maybe they began to view the world below and beyond Walbury Hill as part of something greater – as part of the Roman Empire. We will never know for sure, but, human nature being as it is, this has to be a possibility.

Fast forward some four or five hundred years. On a clear day it might have been possible to spot some activity in the valley below Walbury just to the west of what is now Inkpen.

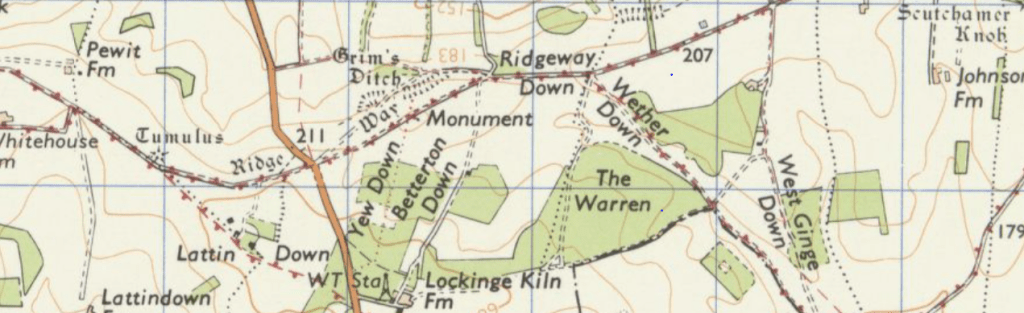

To the left – or west – of the map above, “Wodnes Dic” is the earth work we know today as the Wansdyke. The crossed swords symbols at Ellandun, Beranburgh and Bedwyn indicate that this area sawconflictds during this period, known as the “Dark Ages”.

If you look carefully at modern editions of the OS map for this area, and you will see a track running north to south and just to the east of Lower Spray Farm, Inkpen, at grid reference SU 35170 63746. This is Old Dyke Lane, marked on the map as an earthwork and as a scheduled ancient monument.

Despite the name “dyke”, Old Dyke Lane has nothing to do with drainage, neither is it a scheduled ancient monument just because it is a lane. On some maps, Old Dyke Lane also has the word, “Wansdyke” printed in Old English script, which gives a clue to its historic importance.

The Inkpen section of the Wansdyke is in fact the very eastern end of “Woden’s Dic” – defensive ditch and bank running all the way from Portishead near Bristol, right across Wiltshire and concluding just over the border in what is now Berkshire. In places the bank is at least 4 meters high with the ditch being 2.5 meters deep although when first constructed it is likely to have been both higher and deeper. As the ditch is on the north side of the bank, it is likely that the Wansdyke was built by those living to the south of it for defence against those living to the north.

When first constructed, the bank may have had wooded revetments and a walkway; certainly the chalk of the freshly constructed bank would have been bright white, making a definite statement in the landscape and very likely visible from the hills above.

Constructing such a defensive work as this, at a time when there were only primitive excavation tools available, must have been a colossal feat, so who would have been responsible and whom were they defending themselves against?

There had been suggestions that the Wansdyke was constructed by the Romans but now this idea has been challenged. However, although Roman authority departed Britain around 410 C.E., that did not mean that every last Roman marched to Dover, waved goodbye and got on a boat heading to Italy. By the early fifth century, many who had originally arrived with the Roman army had formed relationships with the indigenous Britons whose culture and way of life had endured despite the occupation. So, by the fifth century, many people could be described as “Romano-British”.

There are, of course, very few written documents from this period of British history and what there are were written by clerics and the religious. Gildas was a monk writing in the 6th century CE and a very early chronicler of British history – although not necessarily a very accurate one.

Gildas believed the Wansdyke was constructed by one Ambrosius Aurelianus, a fifth century Romano-British military leader who fought against the Anglo Saxons as they advancing towards the south west from the north.

The Welsh cleric, Geoffrey of Monmouth was an eleventh century historian with a particular interest in the Arthurian legend. He elaborated on the story of Ambrosius Aurelianus, describing him as the uncle of King Arthur, no less.

It is, of course, completely fanciful to think of the Wansdyke as having any connection – even remotely – with King Arthur. However, it may well have been constructed in the Dark Ages – the time in which the Arthurian legends are set – by Romano- British people as defence against aggression coming from the north.

Alternatively, some archaeologists believe that the Wansdyke could have been constructed in the 8th century by West Saxons as a defence against the Mercians, attacking from the area of the River Severn and Avon Valley.

We can – almost – be certain that the section of the Wansdyke in this area would have been constructed, at least in part, by local people who would have felt the need to defend themselves. Whether those people would have indentified as Romano-British or West Saxon, we shall popbably never know but we can deduce that they felt the need to construct a defensive border to define and defend their territory.

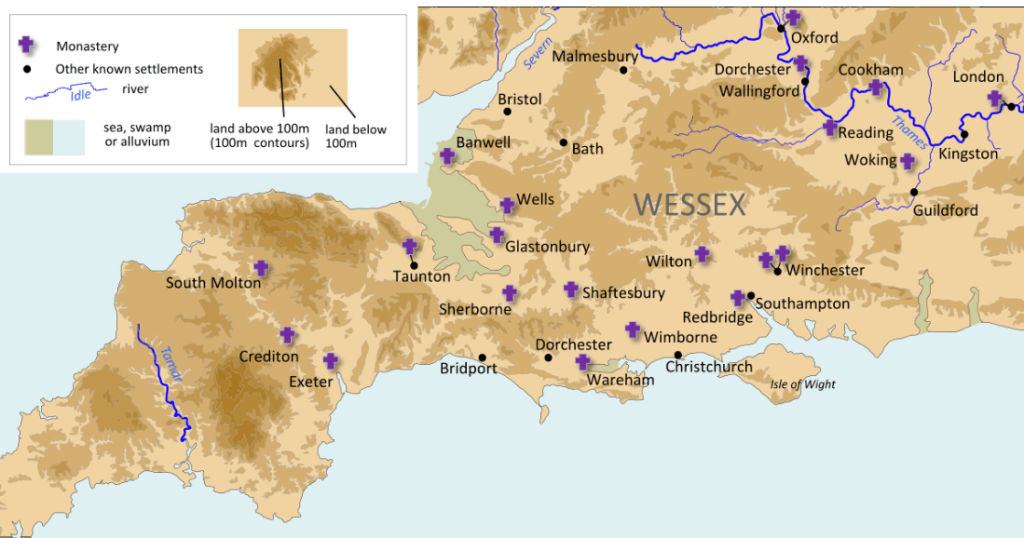

By the 6th century CE, the Anglo-Saxons – incomers from the European mainland – were the dominant authority in what is now England. In our part of the country, that is to say the south and south west, it was the West Saxons who held sway, and our area came to be known as Wessex. For most of this period, the River Thames was the border between Wessex and the Saxon kingdom of Mercia which stretched up into the Midlands.

Cross-border relationships were tense: leaders on each side wanted hegemony over the other Saxon kingdom, and there were frequent battles. A West Saxon person, standing on Walbury Hill and looking northwards, could have regarded the distant hills as enemy territory, to be defended. However a decisive engagement is believed to have come in 825 when Ecgberht of Wessex defeated Beornwulf of Mercia at the Battle of Ellendun, near what is now Wroughton in modern day Wiltshire.

Although relations between those identifying as West Saxons and the Mercians north of the Thames might have become more peaceful, there was to be another potential threat.

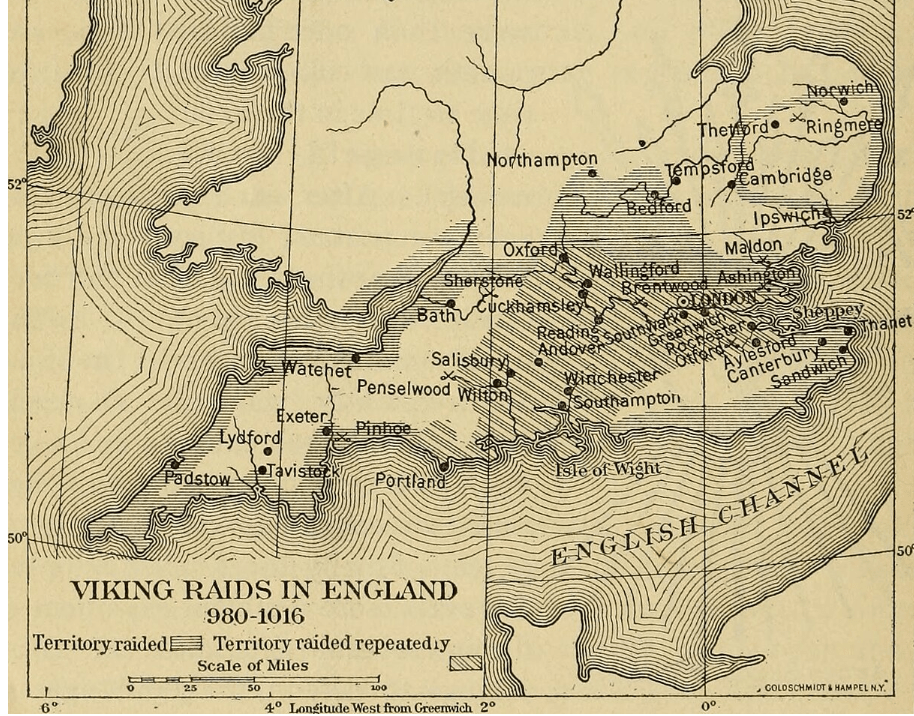

The Vikings had begun to invade and attack towns and villages on the north east coast of what is now England in the late 8th century. The term, “Viking” means pirate or raider and is often used to describe any raiders from what is now regarded as Scandinavia. The raiders from Scandinavia who attacked Wessex in 871 are more accurately referred to as Danes and these are the invaders defeated by (almost) local man, King Alfred at the Battle of Ashdown in 871.

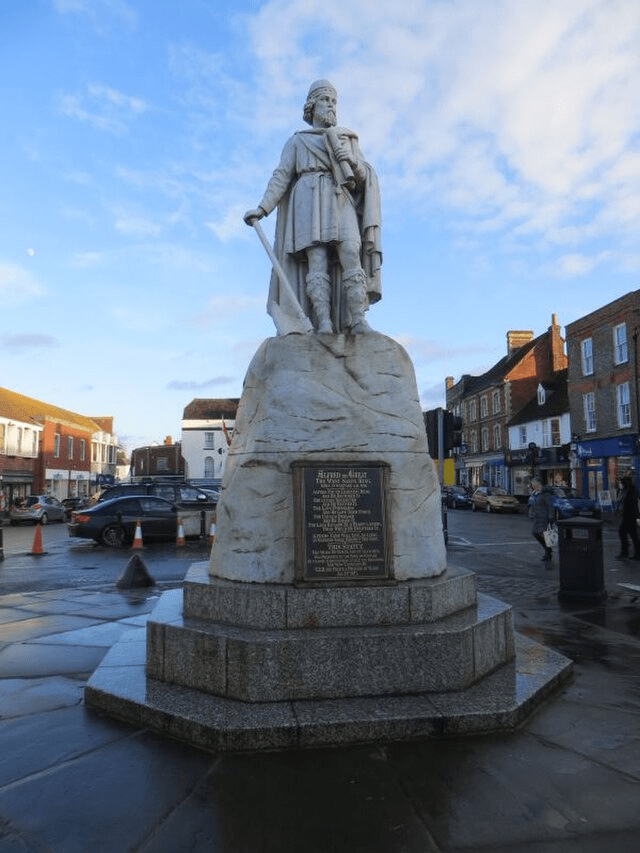

Alfred had been born in Wantage – or Wandesiege as he would have known it – sixteen miles to the north of Kintbury across the downs, in 849. As well as effectively seeing off the Danish threat, King Alfred did much to improve standards of literacy and education in his kingdom and also revised the legal system. He remains the only British monarch to be known as, “the Great.”

By the beginning of the tenth century, a man or woman standing on Walbury Hill would have been looking at Wessex to the north, to the south, to the east and to the west. Now the Kingdom of Wessex was one of the most powerful in what was being called Enga land.

The Saxons were responsible for dividing up the country into administrative areas we know today as counties. Berkshire exists from sometime in the 9th century.

By the Norman conquest, I think it is safe to say Berkshire was a county of size and shape we could identify at least as looking something like the pre 1974 county. However, the final details were not set in stone.

The 1894 Local Government Act resulted in some smaller towns and villages moving from one authority to another. (See my earlier post, “Where in the world is Combe?”)

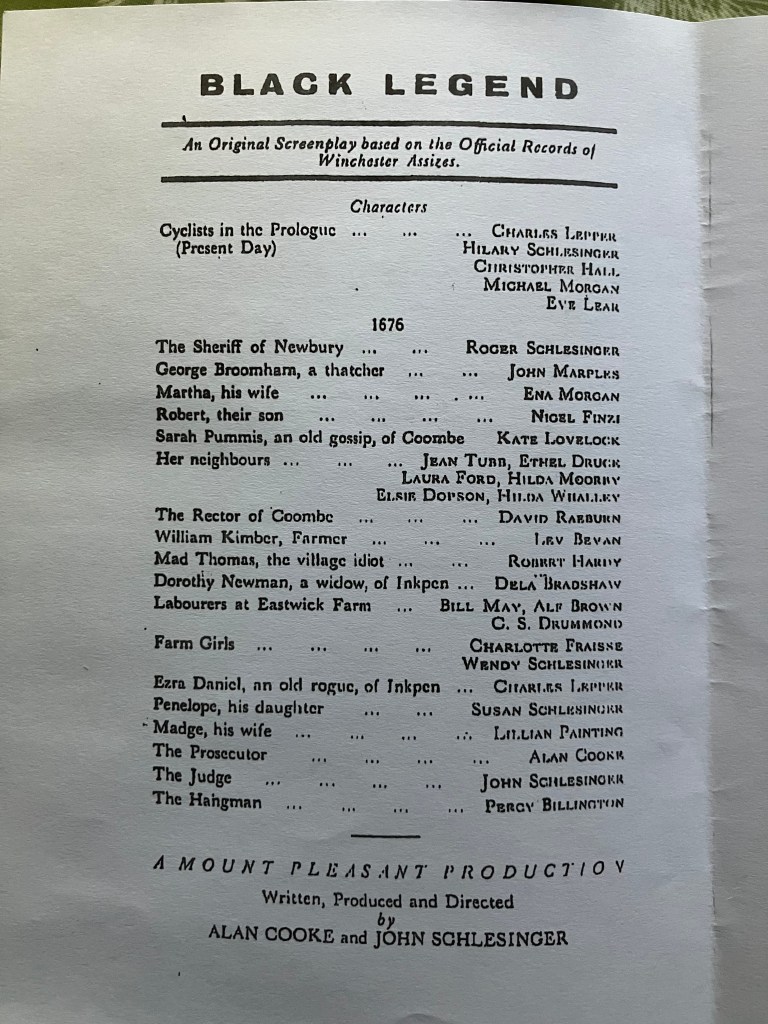

Until 1894, the border between Berkshire and Hampshire ran across Walbury Hill. Combe Gibbet was just inside Hampshire as was the village of Combe. The intention of the Local Government act was to enable the public – by which was meant certain men over 21 – to vote for local and district councillors. Districts were defined by a consideration of certain factors which included not only population but proximity to magistrates courts, banks and poor law unions ( or workhouses.) And so it was decided that for Combe, Hungerford in Berkshire was nearer and more convenient than Kingsclere in Hampshire. The boundary was redrawn therefore, so that Combe and Walbury Hill, along with Combe Gibbet, should be in Berkshire.

But, as far as I am aware, none of these changes were accompanied by violence. In 1894 the good burghers of Charnham Street, Hungerford did not have to defend themselves against Berkshire taking it by force from Wiltshire. And no one in Combe sharpened their pike staffs and marched up Walbury Hill to repel similar forces from Inkpen and Kintbury.

Although the redrawn border between Hampshire and Berkshire was not done for defensive purposes, certain measures taken in 1940 definitely were.

After the defeat at Dunkirk in 1940, Britain faced the severe threat of invasion. Plans were made to delay the German forces should they actually invade, to which end a series of defensive constructions were eventually built which included concrete “pill boxes” at locations along the Kennet & Avon – known as “Stop Line Blue” – and also the Thames. They would be manned by Local Defence Volunteers – men unable for whatever reason to join the regular forces but who could contribute to defence.

Thankfully, there was never an invasion during World War II and so the pill boxes were never used to defend a border. But it is a chilling thought that, if an invasion had been succesful, the Kennet & Avon canal, or even the Thames, could have become the border between a free England and the occupied sector.

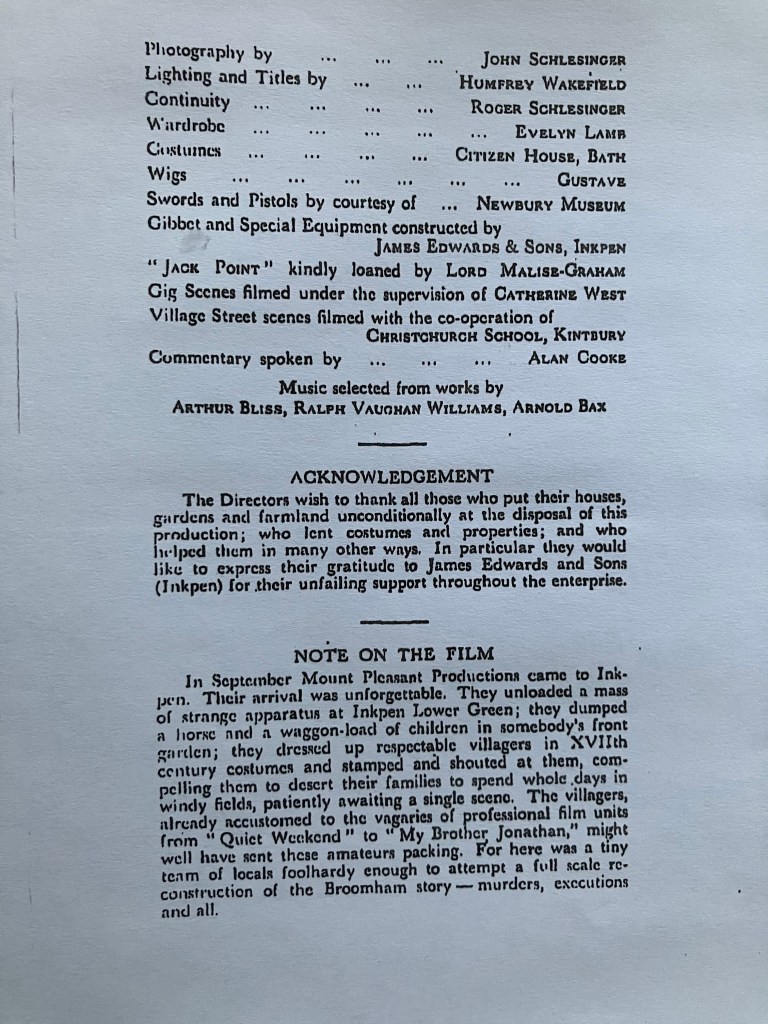

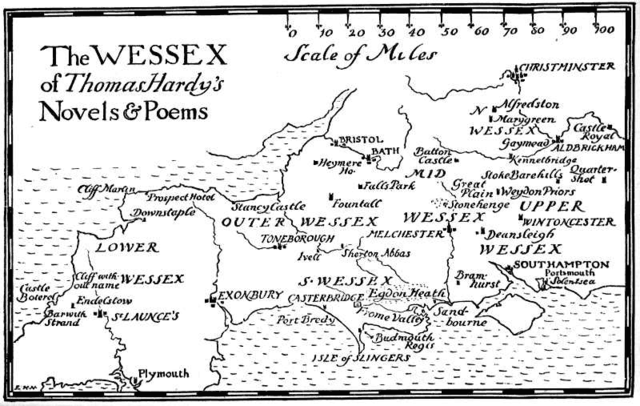

Interestingly, the name Wessex has endured even though Alfred’s Kingdom has long gone. It is as if many of us still take a kind of atavistic pride in living in what was once a very powerful part of England – and perhaps also a very beautiful one. I believe the novelist Thomas Hardy was in part responsible for the resurgence of Wessex as an idea, if not strictly a geographic location, when he used it as locations in his novels.

Speaking for myself, I quite like the name “Ridgeway” and I hope that is what our authority will be called. Alternatively, I rather like “North Wessex” as Thomas Hardy called this area in his novels. But whether we are Wessex or Ridgeway, West Berkshire or Royal Berkshire, Walbury Hill – our highest point in chalk in England – will still be there, and the White Horse will still be galloping over the downs above the vale

(C). Theresa A. Lock 2025

Sources:

http://www.wansdyke21.org.uk/faqs.htm https://howardwilliamsblog.wordpress.com/2022/10/24/exploring-east-wansdyke