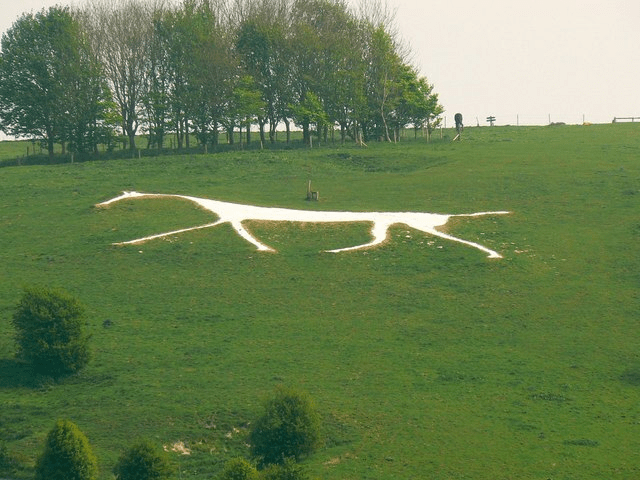

There are many hill figures cut into the chalk downland of southern Britain. The oldest and probably the most famous is the Uffington White Horse in Oxfordshire (formerly in Berkshire before 1974) cut into the scarp slope of the North Wessex Downs overlooking the Upper Thames Valley, which is over 3,000 years old.

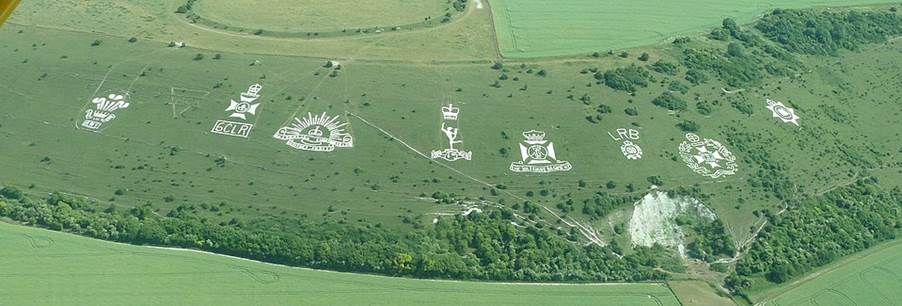

By contrast, the Fovant Badges were originally cut in the years after the First World War. These depictions of military badges were cut to honour the hundreds of soldiers who had been training near the village of Fovant in south west Wiltshire.

Dorset boasts two hill figures. The horse and rider on Osmington Down near Weymouth was created in 1808 in honour of George III, a frequent visitor to the town. However, no one really knows why the Cerne Abbas giant – a figure of more likely humorous or satirical intent – was created above the village in Early Medieval times.

Pete Harlow via Creative Commons

However, the majority of white horses can be found across Wiltshire. The Westbury white horse is believed to have been made sometime in the late seventeenth century which would make it the oldest figure in the county. Next comes the white horse above Cherhill, which is believed to date from 1780. Pewsey’s horse was cut in 1785 and then in 1808, pupils at a boys’ school in Marlborough constructed the town’s white horse.

Brian Robert Marshall via Creative Commons

At Broad Hinton, it is believed that the parish clerk, Henry Eatwell, may have been responsible for the Hackpen Hill white horse, which was constructed in 1838 to commemorate Queen Victoria’s coronation.

Brian Robert Marshall via Creative Commons

The Devizes white horse first appeared in 1845. Then, rather later than the rest, Broad Town in 1885.

But how many people know that, sometime in the early 1870s, Inkpen was added to this list?

The Ordnance Survey map, Berkshire, Sheet XLI, surveyed in 1873 and published in 1877, does indeed show another white horse, situated on the north facing slope of Inkpen Hill and just over the county boundary in Wiltshire.

So, who was responsible for Inkpen’s white horse and what happened that we can no longer see it?

The Inkpen ( or Ham ) white horse was constructed on land owned as part of the Ham Spray estate, just to the east of the small village of Ham in Wiltshire and to the west of Inkpen, Berkshire. In 1869 it was bought by the then thirty year old Charles Wright. In the 1871 census, Wright is described as a farmer of 370 acres employing 8 men and 4 boys, so is clearly quite successful.

Wright had been born in 1839 in the Leicestershire village of Market Bosworth. In 1841 he is living with his grandfather, a clergyman and in 1851 he is a boarder at a grammar school in Derby. By the age of 22 he is living with his father and his older brother Thomas who is in the military. Charles himself is described as “gent”: a very precise distinction at this socially divided time.

Ten years later, Thomas Wright has a seat of his own: Tidmington House in Worcestershire, where he lives with his wife and eight staff. Younger brother Charles has relocated to the south west.

When Charles Wright bought Ham Spray House, it was a modern building still only around thirty years old. Perhaps Charles wanted to establish his own seat, distinct and away from the family in Leicestershire.

Charles Richard Sanders via Creative Commons

Some nineteenth century landowners become high profile figures within their towns or villages and their names feature frequently in the local press. This cannot be said of Charles Wright in the time he lived at Ham Spray House. The only reference I can find to him in local papers, aside from details of the sale of his property, was when he contributed generously, along with other local gentry, to a fund for the sick.

Finding himself in a county famed for its white horses cut into the chalk downland, Wright may have wanted the distinction of adding to that number. Perhaps he wanted to impress his neighbours, or just to add to the view from his house. So, sometime in the early 1870s he had his workers cut the outline of a horse into the downs. The new white horse must have been distinctive enough for the Ordnance Survey surveyors to notice it when working in the area in 1873 and include it on the latest edition of the O.S. map, published four years later..

However, the 1877 O.S. map is the only one to include the new, Inkpen white horse. Sadly, it did not endure partly because it had been constructed by stripping away the turf with out digging and packing out trenches with compacted chalk. Further, subsequent landowners did not bother to clear away the encroaching grass.

Charles Wright died on 12th December 1876 at Ham Spray House. He was only 37. The estate, his house and all its contents were sold. His time at Ham Spray House, like that of his newly cut white horse on the downs above Inkpen, had been brief.

Ancestry

British newspaper Archive

(C) Theresa A. Lock, 2025