We have just had two hampers of apples from Kintbury, and the floor of our little garret is almost covered

Letter to Cassandra Austen, October 1808

In her letters, Jane Austen frequently referred to Kintbury and to local people, several of whom became members of her extended family or close friends. In this article we discuss who these people were.

.

THE CRAVENS

Lord William Craven 1770 1825

Lord Craven has probably other connections and more intimate ones, in that line, than he now has with the Kintbury family.

Letter to Cassandra, 1799

“Eliza has seen Lord Craven at Barton & probably by this time at Kintbury, where he was expected for one day this week. – She found his manners very pleasing – the little flaw of having a mistress now living with him, at Ashdown Park, seems to be the only unpleasing circumstance about him.”

Letter to Cassandra, January 1801

The Barton Jane refers to in this letter is Barton Court, Kintbury. By 1801, when the letter to Cassandra was written, Barton Court was the home of Charles Dundas and his wife Anne.

Lord William Craven was a distinguished military gentleman, served in Flanders and was AD to the King and a favourite of Queen Charlotte. A bit of a rake before his marriage, he kept his mistress, Harriet Wilson, at Ashdown House on the Berkshire Downs. After Harriet, having become tired of him, left, he went on to marry the actress, Louisa Brunton. They lived in Hamstead as a close family and the Countess was renowned for her gracious generosity.

Other members of the extended Craven family had power and influence across the West Berkshire area during the eighteenth century.

THE FAMILY OF CHARLES & ELIZABETH CRAVEN

“Governor” Charles Craven, 1682 – 1754, of Hamstead Marshall had been Governor of Carolina between 1711 and 1716. His wife, Elizabeth, 1698 – 1771, gained a reputation as a socialite and it is alleged that she treated her children badly.

Charles & Elizabeth had one son, John.

Rev’d John Craven 1732 – 1804

My Uncle is quite surprised at hearing from you so often – but as long as we can keep the frequency of our correspondence from Martha’s uncle, we will not fear our own.

Letter to Cassandra, 1799

The Martha referred to here is Jane’s close friend Martha Lloyd. Martha’s uncle was John Craven son of “Governor” Charles Craven & his wife Elizabeth of Hamstead Marshall.

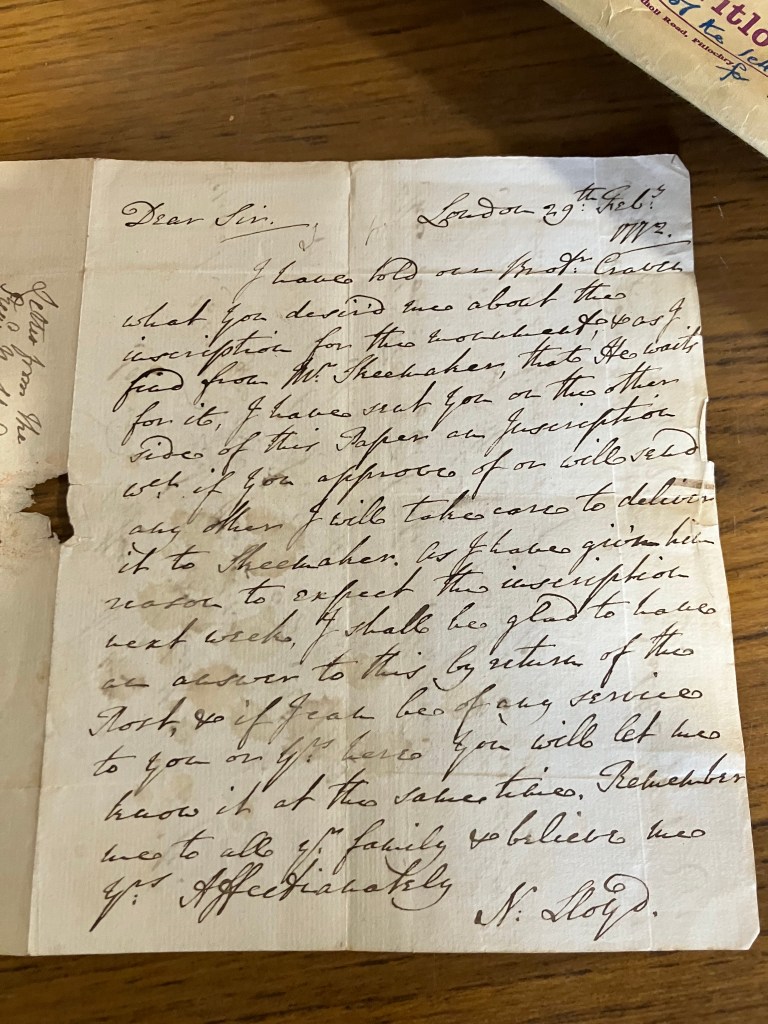

When his widowed mother, Lady Elizabeth Craven, married the besotted Jemmet Raymond she proceeded to marry John to Jemmet’s sister, Elizabeth. Elizabeth was well off, but judged to be weak in intellect. They married in Kintbury in 1756.

Married for 20 years, John and Elizabeth did not have children so one might presume that the marriage was in name only. When Elizabeth died, Barton Court passed to another branch of the Raymond family.

Jane Fowle, nee Craven 1727 – 1798

I am very glad to find from Mary that Mr & Mrs Fowle are pleased with you.

Letter to Cassandra, January 1796

Jane Craven was the second daughter of Charles & Elizabeth Craven of Hamstead Marshall. In 1763 she married Rev’d Thomas Fowle of Kintbury and the couple had three sons: Fulwar Craven, Thomas, William & Charles.

Martha Lloyd, nee Craven 1729 – 1805

James I dare say has been over to Ibthrop ( sic ) by this time to enquire particularly of Mrs Lloyd’s health.

Letter to Cassandra, May 1801

Martha was Charles & Elizabeth Craven’s third daughter.

In 1763 Martha married the Rev’d Noyes Lloyd and the couple had three daughters: Martha, Eliza & Mary, and one son, Charles.

From 1771 until his death in 1789, Rev’d Lloyd was Rector of St Michael’s, Enborne. Sadly, in 1775 there was an outbreak of smallpox in the village and, whilst the girls survived, their brother Charles, aged 7, died.

Following Noyes’ death, his widow along with daughters Martha and Mary, moved to Ibthorpe (“Ibthrop.”)

THE FAMILY OF MARTHA & NOYES LLOYD

Eliza Lloyd 1768 – 1839

(Mrs Fulwar Craven Fowle)

Eliza says she is quite well but she is thinner than when we last saw her and not in very good looks. She cuts her hair too short over her forehead and does not wear her cap far enough upon her head. In spite of these disadvantages, I can still admire her beauty.

Letter to Cassandra, January 1801

Eliza Lloyd was the eldest daughter of Rev’d Noyes Lloyd and his wife, Martha, of Enborne.

In 1788, Eliza Lloyd married her cousin Fulwar Craven Fowle. They had eight children, one of whom died as a baby. The last child, Henry, was born when Eliza was 39. Eliza died in 1839 aged 71 and Fulwar the following year aged 76.

Martha Lloyd 1765 – 1843

(Lady Austen)

She is the friend & Sister under every circumstance’.

Letter to Cassandra, 1808

Martha was the eldest daughter of Rev’d Noyes & Martha Lloyd of Enborne.

Martha had been born in Bishopstone in Wiltshire then moved with her family to Enborne near Kintbury where her father became rector of St Michael’s. On her father’s death, Martha, along with her mother and sister Mary, moved to Ibthorpe where they became frineds with Jane & Cassandra Austen.

Following the death of George Austen in 1805, Martha joined Jane, Cassandra and Mrs Austen at their home in Bath, later moving with them to Southampton and eventually settling in Chawton.

In 1828 Martha married Jane’s brother, Captain Frank Austen RFN. Martha died in 1843 and is buried in Portsdown.

Mary Lloyd 1771 – 1843

(Mrs James Austen)

Mary does not manage matters in such a way as to make me want to lay in myself. She is not tidy enough in her appearance; she has no dressing gown to sit up in; her curtains are all too thin, and things are not in that comfort and style about her which are necessary to make such a situation an enviable one.

Letter to Cassandra, November 1798

Mary was the youngest daughter of the Rev’d Noyes & Martha Lloyd of Enborne.

Unlike Martha, Mary does not seem to have been a great favourite of Jane’s. When James Austen was widowed in 1795 he first turned his attentions to his widowed cousin Eliza. However, she did not return James’ affection and later married his brother Henry. When James married Mary Lloyd in 1797, it is said that she did not forget that she was second choice. Mrs. Austen however, was very pleased with the marriage and said that Mary was the daughter in law that she would have chosen.

Whether great friends or not Mary helped nurse Jane in her last weeks. In her widowhood she lived at Speen with her daughter Caroline. She died in 1843.

THE FOWLE FAMILY of KINTBURY

Rev’d Thomas Fowle 1726 – 1806

I am very glad to find from Mary that Mr & Mrs Fowle are pleased with you.

Letter to Cassandra, January 1796

Rev’d Thomas Fowle became vicar of Kintbury in 1762 when he succeeded his father, also called Thomas, and who had become vicar here in 1741.

In 1763 Thomas married Jane Craven of Hamstead Marshall. Thomas & Jane had four sons: Fulwar Craven, Thomas, William & Charles.

Thomas was succeeded as vicar of Kintbury by his son, Fulwar Craven Fowle in 1789.

THE FAMILY OF JANE (NEE CRAVEN) & REV’D THOMAS FOWLE

Fulwar Craven Fowle 1764 – 1840

“We played at vingt-un, which, as Fulwar was unsuccessful, gave him an opportunity of exposing himself as usual.”

Letter to Cassandra, January 1801

Fulwar Craven Fowle was vicar of Kintbury from 1798 until 1840.

Born in 1764, Fulwar was the eldest son of Thomas & Jane Fowle of Kintbury. He studied at Steventon under Jane Austen’s father, George Austen then went up to Oxford graduating in 1781. In September, 1788, he married his cousin, Eliza Lloyd.

Physically he has been described as rather short and slight with fair hair, very blue eyes and a long nose. In character he was impatient, rather irascible at times and hated losing at games as Jane hinted at in her letters.

When, despite many applications for mercy, Kintbury Swing Rioter William Winterbourne was hanged, Fulwar brought his body back home and had a tomb stone erected to his memory.

Eliza Fowle died in 1839, and the weeks before and after her death appear to be the only times in his long career that Fulwar failed to minister to his flock . On 9th March, 1840, he died in his 76th year. He was, as his memorial testifies, a conscientious and outstanding parish priest in an age when it was not always so.

Tom Fowle 1765 – 1797

“How impertinent you are to write to me about Tom, as if I had no opportunities of hearing from him myself.”

Letter to Cassandra, January 1796.

The second son born to Kintbury’s Thomas & Jane Fowle.

Tom Fowle had been born in 1765, studied at Steventon under George Austen, graduated from Oxford in 1783 and became ordained into the Church of England in 1790.

Tom was a kinsman of William, Lord Craven, and served as his chaplain on the military expedition to the West Indies in 1796, probably to earn money to enable him to marry Cassandra Austen, to whom he had become secretly engaged.

Sadly, he died in the West Indies of a fever, caught after bathing in great heat (according to his family) or possibly of Yellow Fever according to other sources. Yellow Fever was endemic amongst the British troops in the West Indies.

William Fowle 1767 – 1806

“Tell Mary that there were some Carpenters at work in the Inn at Devizes this morning but as I could not be sure of their being Mrs W. Fowle’s relations I did not make myself known to them.”

Letter to Cassandra, May 1799

William Fowle was the third son of Kintbury’s Rev Thomas Fowle & his wife Jane.

Born 1767, he became a physician after being apprenticed to his uncle, Dr. William Fowle. In October, 1791, he graduated in medicine from the University of Leyden.

In 1792 William married Maria Carpenter and went to live in Devizes, her home town. He was admitted to the College of Physicians 25th June, 1795 and went on to join the army as a physician. He saw considerable service in the West Indies and Egypt, dying there in 1801 aged 35.

William had a particular interest in the treatment of diseases, writing a dissertation on Erisyphlas which he dedicated to Charles Dundas, a paper, Experiments with Mercury in the Small Pox, translated from the French in 1793, and A Practical Treatise on the Different Fevers of the West Indies in 1800. This is rather poignant as his brother died there of a fever.

William and Maria had two children, Marriane & Charles, both of whom were baptised in Kintbury. Sadly, Maria and the children were left unprovided for when William died and in 1802 Maria was granted an annual award of £50. This was in consideration of the sufferings of her husband whilst in the Mediterranean and Egypt and his having died in service

Charles Fowle 1770 – 1806

“What a good-for-nothing fellow Charles is to bespeak the stockings – I hope he will be too hot all the rest of his life for it!”

Letter to Cassandra, January 1796

Charles was the youngest son of Kintbury’s Rev Thomas Fowle & his wife Jane.

Born 1770, Charles studied law and in 1800 it was announced that the Honourable Society of Lincolns Inn had been pleased to call Charles Fowle Esq, a Fellow of the Society. In 1799 he married Honoria Townsend in Newbury and later went on to practise law in the town.

During the Napoleonic wars, Charles Dundas asked him to form the Hungerford Pioneers, a group, said his family, comprised of worthy ironmongers and bakers.

It is thought that he had a teasing relationship with Jane. They played tricks and called each other names. Perhaps the silk stockings he was commissioned to buy her came from the Kintbury silk mill.

THE DUNDAS FAMILY OF BARTON COURT

Mrs Anne Dundas

Martha … is to be in town this spring with Mrs Dundas

Letter to Cassandra, January 1809

The Mrs. Dundas referred to here is Anne Dundas, nee Whitley, wife of Charles Dundas, M.P. Anne was the heiress who inherited Barton Court, Kintbury, when Elizabeth Raymond, formerly Craven, died.

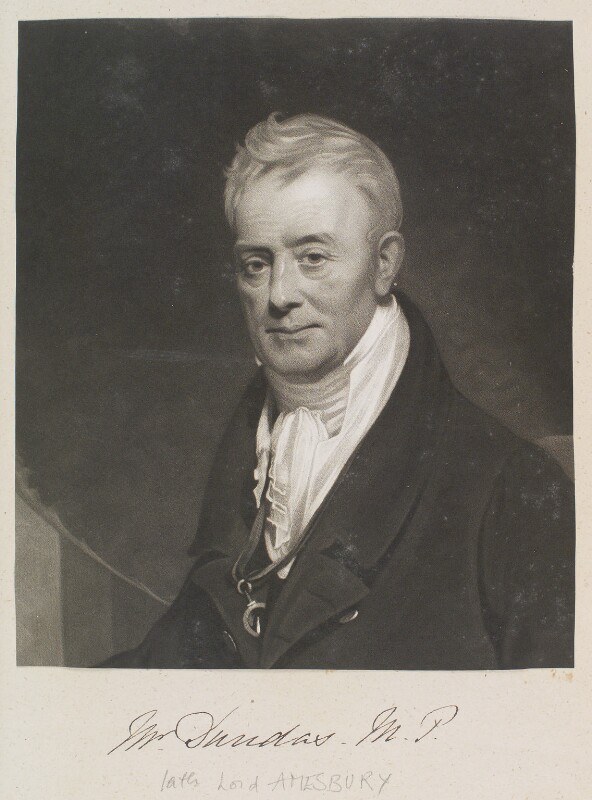

Charles Dundas, Baron Amesbury:

Younger son of Thomas Dundas of Fingask, MP for Orkney and Shetland, Charles was born in 1752 and called to the Bar in 1777. As an M.P., it was said that he was ’liberal in politics’ and at one time expected to become Speaker.

Charles came into possession of Barton Court when he married Ann Whitley, member of the Raymond family.

He became a peer on 11th May, 1832 but died two months later of cholera.

Charles Dundas

References & sources:

The letters of Jane Austen Ed Deirdre Le Faye

The Creevy Papers

Greville’s Diary

The Gentleman Magazine

The British Newspaper Archives

The Dundas Papers

(C) Penelope Fletcher 2024